By Susan Blumberg-Kason

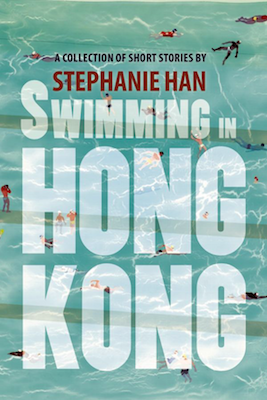

I met Stephanie Han at a literary event in Hong Kong back in 2014, but we didn’t get much of a chance to talk due to traffic delays, linked to the Umbrella Movement’s ongoing occupation of the financial district, making me arrive late. We connected a few months later when I Skyped into a memoir-writing class she was teaching on Lantau Island in Hong Kong. I only really got to know her, though, via a different sort of virtual encounter: reading and becoming absorbed by Swimming in Hong Kong, her new collection of short stories. Comprised of tales that previously appeared in periodicals and anthologies, it is published by Willow Springs Press. Here are some questions I emailed her, along with the answers she sent back.

SUSAN BLUMBERG-KASON: Your book includes four stories set in Hong Kong with a diverse group of characters, from a Korean expat to Cantonese senior citizens to an African-American woman, and a working class Cantonese man and his young daughter. You get at the crux of many Hong Kong social problems and demonstrate a good feel for the place. How long did you live there, and what took you there in the first place?

STEPHANIE HAN: I first went through Hong Kong as a tourist at the time of the 1997 Handover — that’s when I met my husband. He’s a Brit, so he lived there like many Brits did when it was a colony. I first moved to HK in early 2002, stayed a year, went back to the US for my MFA, and then moved back to HK in 2008. I’m not an insider to life in Hong Kong — I’m Korean American, and on one side, four generations into US life, so Hong Kong for me was never about searching for my cultural identity, and my relationship to Asia (as well as the US) is quite different from many Asian Americans who are first or second generation immigrants on both sides. I was a witness. The people there are now searching for answers and ways to live that are complicated, moving, and often quite painful to witness. For me, it was never an easy place to live for many reasons, but I see the pathos there, as well as what people long for it to be, and it was a place we could find economic opportunity.

The stories in Swimming all deal with race and identity, specifically the feeling of invisibility, which is especially pertinent to the atmosphere in the U.S. now. Did you set out to tackle the issue of invisibility, or did it evolve as you wrote?

I didn’t set out to address this issue of invisibility, but I think that the idea of silencing, of being invisible, of being unseen, is one familiar to many individuals or groups of people who are occluded from a mainstream narrative of community or national/cultural identity. Being different, understanding an idea of the Other is very important to me. There’s always a story underneath the story that everyone knows. But I did not set out to thematically tackle this invisibility issue within the collection. Understanding the complexities and conflicts of visibility/invisibility was a personal issue to me that I think, like most writers, I tried to better understand through creating stories. The stories were written over a number of years. I think if the collection were ordered chronologically, it might look quite different and this theme may not be so apparent. Also the final published version didn’t include one story that was originally in the completed collection. Presentation affects how we perceive ideas.

You earned the first PhD in English Literature from the City University of Hong Kong. Why did you decide to pursue a doctorate and what was the topic of your dissertation?

I was asked to apply by the former chair and so I did. It had never occurred to me before that to pursue a PhD, but I got offered full funding and it was a chance to be paid to study and write. My dissertation is now a revised manuscript titled The Art of Asian America: Globality, Aesthetics, and the 21st Century Asian America Novel. I write about the aesthetic terms and formal devices found across the genres, in the novels of Gish Jen, Amitav Ghosh, Karen Tei Yamashita, and Adrian Tomine. Critics and readers have denied that there are specific traits to this fiction — but I prove otherwise and also recast, for the purposes of literary criticism, the very definition of the term “Asian America/n.” It’s a new way of reading Asian American texts within the context of global modernity. I’m looking for a publisher now! I also finished a poetry manuscript during this time, Passing in the Middle Kingdom, now under submission. I’d go back and forth between criticism and poetry. They work different writing muscles.

Can you discuss Swimming in Hong Kong’s path to publication?

The path was long, miserable, and unpleasant all around. I was annoyed, pissed off, angry, depressed, but due to my stubbornness, and probably the masochist in me, I kept going. My dad always told me, “fall down seven times, get up eight times.” If I could think of something other than writing to do, I would have done it, but I couldn’t. This, however, points to the limits of my imagination, more than anything else. You know those people who keep their rejection slips? Are you kidding me? It would fill an entire filing cabinet if I did that! The collection was more or less done by more than a decade ago. At one point, I just quit sending it out, as I couldn’t afford the postage or time or fees. I was rejected everywhere by everyone. I submitted to agents, journals, anthologies, this, that. I received enough encouragement to keep on going, several of the stories won individual prizes. I entered it in the AWP and Spokane prize and that is finally when the book was published — I’m very grateful Willow Springs published it!

There are two lessons to take from this. First, you really have to find purpose and pleasure in the work itself. And second, remember that many writers write of a future (even if they set there work in the past) that does not yet exist for most people. When I wrote some of these stories, people — editors or gatekeepers — were simply not open to publishing the things in them, from discussions of intersectional feminism, to a portrayal of a friendship between a young black woman and an old Chinese man, to the experience of Asian expatriates. The book was published because now people see and accept the ideas, characters, and relationships in them. I wasn’t trying to be futuristic. That was just how I saw life based on my experiences and perceptions. Interestingly enough, I think I am a very different writer and reader now—the last story was written more than a decade ago. But it’s okay. We are never the same readers and writers throughout life—we constantly change.