By Austin Dean

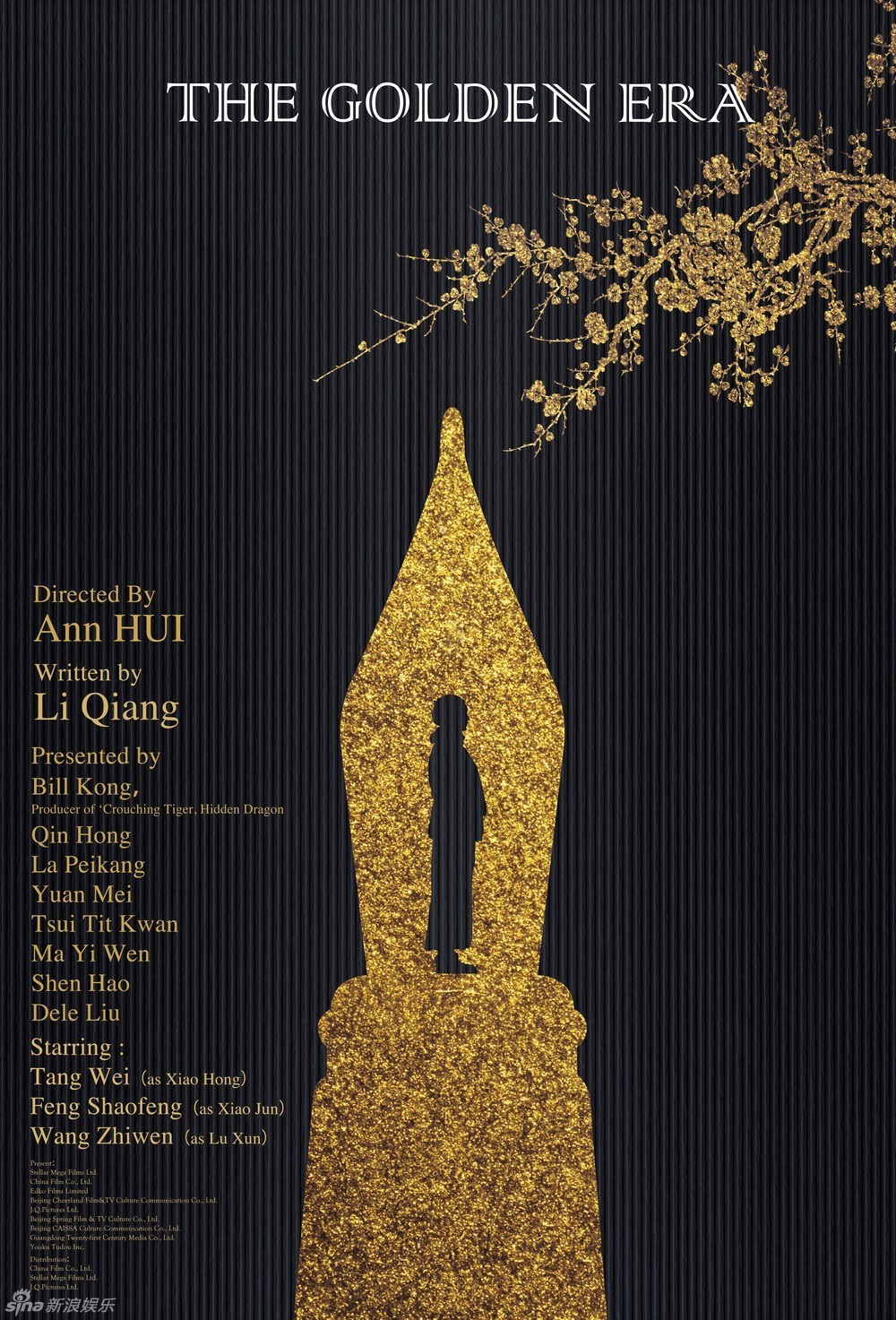

The writer Xiao Hong is everywhere in China these days. Her face recently graced the covers of a score of newspapers and magazines; the publication Sanlian Weekly devoted over thirty pages to her; billboards advertised the recently released film about her career. In fact, the new film The Golden Era is the second Xiao Hong biopic to come out in the space of just two years—the first one, Fallen Flowers, hit theaters in March 2013. A remarkable accomplishment, particularly since Xiao published most of her work in the 1920s and 1930s and passed away in 1942.

She is not the only Chinese literary figure from that period experiencing a good several years. In 2007, director Ang Lee’s movie Lust, Caution brought renewed attention to the writings of Eileen Zhang (Zhang Ailing). Zhang also burst to fame in the period prior to the establishment of the People’s Republic of China before leaving the country in the early 1950s and finally settling in the United States. Had it not been for the political division of Taiwan and the People’s Republic of China, one scholar argued, she would have been a sure candidate for the Nobel Prize in literature. Likewise Hu Shih, an important intellectual figure in the 1920s and 1930s who emphasized the importance of writing in vernacular as opposed to the esoteric structure of classical Chinese, was out of favor for many years in China. In the 1950s, the Communist Party labeled Hu’s beliefs—heavily influenced by American advocates of pragmatism like John Dewey—as examples of bourgeois ideology that had to be opposed. He was a scorned figure on the mainland. Now, his works and diaries are freely available.

Why so much renewed attention on the literary and cultural figures of this period?

It’s easiest to start with the political reasons. The victory of the Communist Party and the establishment of the People’s Republic of China naturally meant the repudiation of much of the legacy of the Nationalist period in the 1920s and ‘30s, when China was under the control of the Guomindang. The Nationalist regime, according to this narrative, was corrupt, inept, and suffered from a host of internal problems; in addition, Chiang Kai-shek and the Guomindang leadership failed to actively oppose the Japanese invasion in the 1930s. This narrative is easily spotted on display on television screens any night of the week in China, as entire channels are devoted to drama series that show the misdeeds of craven and corrupt officials from the Nationalist government while heroic young Communists battle the Japanese. However, during and after the period of Reform and Opening, which began in 1978, many literary figures benefitted from being reexamined for their contributions to China instead of their supposed crimes against the country. Hu Shih fits squarely into this category, with the mainland historian Ji Xianlin penning a famous essay in his defense during the 1980s.

But although political narratives can explain a lot, they cannot explain everything. When asked about the popularity of setting movies and television series in the 1930s, the actress Tang Wei, who made her breakthrough performance in Lust, Caution and portrays Xiao Hong in the in the recently released biopic, explains the phenomenon in terms of the spiritual and sentimental rather than the political. For Tang, this period of Chinese history has an innocence and simplicity, but its leading personalities maintained a high-minded idealism. The implication here, of course, is that China today is devoid of these characteristics.

Professor Ai Xiaoming of Zhongshan University in Guangzhou thinks the appeal of the period, and Xiao Hong in particular, is tied to how quickly Chinese society was changing and how the world of Chinese women was quickly expanding. Born to a landowning family in the north of China and educated in a girls school in the 1920s, Xiao ran away from home to avoid an arranged marriage, then embarked on more than a decade of criss-crossing China, living in Qingdao, Shanghai, Xi’an, Chongqing, and Hong Kong. The recently released biopic of her life plays up the idea of independence with the English tagline “Be who you want to be.” That is a line with a lot of resonance for today’s youth in China.

An alternative answer for the renewed attention to the 1930s and 1940s is that the period closely resembles Chinese society today, making it a fruitful area for artistic endeavor. Even though actress Tang Wei talks about the differences between China today and China of the period before the establishment of the PRC, they share number of characteristics, chiefly cosmopolitan Chinese cities of the coasts awash in international influence, economic inequality, and government corruption.

In fact, one of the most popular shows currently airing on Chinese television, All Quiet in Peking, focuses on the period of 1948 and 1949, right before the final fall of the Guomindang government. As the scriptwriter Liu Heping said in an interview, he completed the script seven years ago but had difficulties finding investors to back the project because they thought it would not be popular and fail to make money. After finally securing money last year, the beginning of filming overlapped with the start of the anti-corruption campaign by the Communist Party. This past week the most viewed article on the website of the newspaper Southern Weekend, a publication based in Guangzhou, was titled “What is ‘All Quiet in Peking’ trying to say?” For many, it is an allegory about corruption and has a particular resonance in the current political climate.

No matter on the big screen, the small screen or in bookstores, the legacies of the Nationalist period resonate today.