This is the second in a BLARB series made up of interviews with some of the people who will be playing key roles in the soon-to-launch LARB China Channel. This week’s Q&A is with Nick Stember, who has worked both as a writer and a translator, with his special areas of focus including Chinese science fiction and comics. JW

JEFFREY WASSERSTROM: You’ve done a lot of work doing two different hats: that of a translator and that of a writer. Could you tell us a bit about one thing you are particularly proud of doing wearing each of those hats?

NICK STEMBER: It’s funny, but I’ve never really thought of myself as a writer. I started blogging to bring attention to my work as a cultural historian. But, given my interests and background, I’ve never felt very comfortable in academia. That said, I’m proud of the work I’ve gotten to do on Chinese cartoonists from the 1920s and 30s, both on my blog and in more formal settings. I wrote my MA thesis on the Shanghai Manhua Society, a group of influential artists who are widely considered to have been the first to draw “manhua” or “cartoons” in China. Well, that’s an oversimplification in a lot of ways, of course, because it depends a lot on how you define “cartoon” or “comic.” But they’re a fascinating group, and I had a lot of fun getting to know them quite well over the course of my research.

As a translator, I think the most challenging work I’ve taken on so far is probably translating Jia Pingwa, an author from Shaanxi who started making a name for himself in the 1980s. Much of his work straddles the rural-urban divide, and he’s famous in China for crossing boundaries and for his allusions to the older tradition of Chinese literature, often in unexpected ways. I’m working on two books by him: his most recent, The Poleflower, a pretty grim story told from the perspective of a young woman who is abducted and essentially loses her mind after being sold into sexual slavery; and Master of Songs, a history of 20th century China told through the lens of the Warring States (475-221 BC) bestiary The Classic of Mountains and Seas.

What is the most unusual project you’ve taken on as either a writer or a translator?

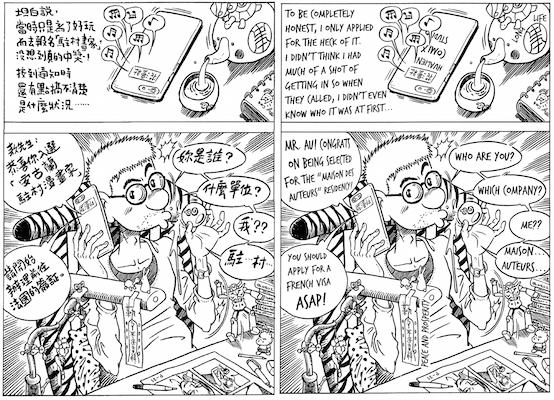

The most unusual project has probably been the ongoing Books from Taiwan Manhua project, a collaboration between the Grayhawk Agency and the Ministry of Culture of Taiwan. We’re on our third year, and it’s been amazing to see how diverse Taiwanese comic books are right now. What’s unusual about this project is that after I translate the comics, I have to re-letter them, too, trying to match the fonts or handwritten Chinese as best I can in English. Back in high school my friends and I used to make (honestly, pretty terrible) Xeroxed minicomics, so it’s been fun to dust off the comics-making part of my brain while also working on something so closely related to my interests. The other unusual part about this project has been coming up with creative ways to deal with the fact that Chinese is much more visually concise than English. I either have to edit my translations way down, or find a way to make the speech bubbles much bigger!

Did you go first to Hong Kong, Taiwan, or the mainland, and what led you there?

Mainland. I spent the 2007-8 school year ostensibly taking Chinese language courses at the Harbin Institute of Technology. I’d been studying Chinese for about a year then, and a certain China blogger convinced me that Harbin was the best city to go to pick up really standard Mandarin. More generally, though, I was getting burnt on my night job, doing data entry and document scanning. After dropping out of high school and spending my teens on a pretty rebellious path, I’d enrolled in college as an older student in a very pragmatic frame of mind, planning to major in something practical, like comp sci. But I kept getting sucked into language and literature classes.

Tell us more about what work you’ll be doing as a Commissioning Editor of LARB’s China Channel? Are there any tips you want to give prospective contributors of the sort of things you’re particularly interested in having them pitch to you?

I see my work with LARBCC as being about introducing atypical Chinese authors, artists, and filmmakers to a larger audience. As a translator, I would like to bring more attention to how incredibly challenging it is for Chinese books and films to succeed abroad. I’ve been thinking a lot about something that Bertrand Mialaret said recently, which was that “[the] themes and narratives that we broadly associate with literature in the West are actually very marginal in Chinese popular literature.” I think that gets to the heart of the problem, because, when we look at it from the other direction, there just doesn’t seem to be any guarantee that books or movies that do well in English-speaking countries will find an audience in China. We have whole genres of literature that just don’t exist there, and the opposite is of course true as well. As a North American, whether we are talking about literature or film or music, I think we are too used to thinking that international means “Europe.” For prospective contributors, think of me as the nerd’s China nerd. Interviewing gender-bending cosplayers? I’m your man. Looking for a place to screen your epic video essay on sinofuturism? Hit me up. Think you’ve found the new Chinese Game of Thrones? Look no further.

Switching gears a bit, I’ve been asking everyone I interview for LARB if there is any recent book on China that you wish had gotten more attention? Or if you’d like to tell us to watch for something that you know is in the works, that’s fine, too.

It’s not exactly a new book, but I picked up a copy of Bill Porter’s Yellow River Odyssey (Chin Music Press, 2014) at the Association for Asian Studies’ annual meeting last year, and I really enjoyed it. I love how he draws out the history of what today might otherwise be pretty unremarkable places. It’s also a great look at what it was like to travel off the beaten path in China in the early 90s. As a translator of Buddhist and Taoist texts and poetry (under the pen name Red Pine), Porter is one of the few people writing about China today (for a general audience at least) who treats religion there as a living tradition. It makes a nice compliment to Ian Johnson’s more recent book, The Souls of China: The Return of Religion After Mao (Pantheon, 2017).

Also, sneaking in another pitch for Jia Pingwa here, he has a reputation for being hard to translate, but that’s been changing with some of the really excellent (and criminally overlooked) translations that have been coming out of his work, with Howard Goldblatt’s translation of Ruined City (University of Oklahoma Press, 2016), and Nicky Harman’s forthcoming translation of Happy Dreams (AmazonCrossing, 2017).

Same question but with a twist: is there a recent book on China, scholarly or popular, that you wish was getting less attention now, or a past one that you wish did not have as much influence when it came out or such lasting influence now?

To be completely honest, I’ve had to take a step back from China books. Understanding China from a political and economic perspective is of course always important, but I worry about our obsession with “reading the tea leaves” in China. Now that the US economy is doing better, opinions on China have shifted to become more positive. But I think in a lot of ways China is used as scapegoat for domestic problems, as we saw with Trump and the GOP during the last election. Living in Vancouver, I also see an enormous amount of tension over the (alleged) impact of Chinese money on the real estate market, but very little attention being paid to other parts of the puzzle, like rising income inequality and job insecurity. So, in general, I wish we were reading more books about (and by) Chinese people and fewer books about policy and business.

I’ve also been asking, is there any famous China book or film that you know you really should have spent time with but haven’t been able to bring yourself to actually read or watch?

I hate to say it, but I’ve never actually sat down and read The Analects straight through. It’s probably about time I did, though!

Header image from Bonjour Angoulême by Ao Yao Hsing 敖幼祥.