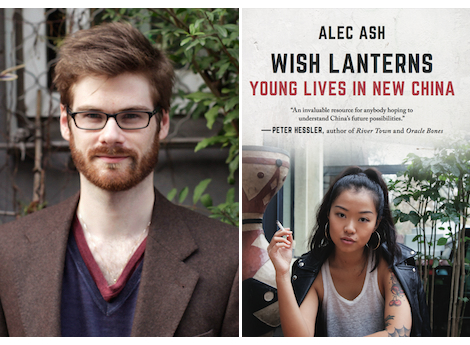

During the upcoming weeks, BLARB will be running interviews with some of the people who will be playing key roles in the LARB China Channel. Regular readers of the China Blog will, of course, be familiar with some of the people interviewed, but they may be curious to learn what these individuals have been up to lately. For others, this will be a chance to get to know some of the writers and editors involved in what will soon be the newest addition to the LARB constellation of channels. This first in the series is a Q&A with Alec Ash, a British writer based in Beijing, whose first book, Wish Lanterns: Young Lives in New China, has been reviewed favorably by, among others, Howard French and John Pomfret, two journalists with very strong China-related track records.

¤

JEFF WASSERSTROM: Let’s begin with Wish Lanterns, which was published in the U.S. earlier this year. How did you end up writing this book, your first, about the experiences of Chinese people born between the mid-1980s and early 1990s?

ALEC ASH: I wrote about this generation because it’s my own. When I first came to live in China in 2008 I was 22, and I spent most of my twenties in Beijing. In that Olympic summer, everyone was talking of how China might change the world. But to me it was how young Chinese are changing that was the real transformational story, with the deepest long-term consequences for the future of China and us all. Now I’m 31, and the so-called “youth” are a different generation entirely. But for those born between 1985 and 1990 — six of whose stories I follow in the book — I think of them as a transitional generation that encapsulates much of the change China is going through. A wedge generation, slowly prising China open but still stuck themselves. That’s why I wanted to tell their stories, and to do so I cast the net wide to find people from different backgrounds. I hope that it forms a wider mosaic, showing the larger generational story through their individual lives.

What was your research and writing process as you tried to uncover enough about their lives to profile them?

I researched and wrote the book over four years, but I didn’t even have my notebook out for the first month or two with each character. We were just eating and drinking together, going to karaoke, getting to know each other, building trust as it were. The best material I got was always in the down moments, when just idly chatting. It was important to me that I visited each of their hometowns with them, to see their childhood haunts with my own eyes. But I also did longer sit-down recorded interviews, to get their backstories straight. The book’s structure is very narrative, interweaving their stories from childhood to present-day, and the first two-thirds of the book is back-reported, as I only entered their lives and witnessed scenes first-hand later in their lives. But I myself don’t appear in the book until the author’s note at the end, as I wanted the focus to be on telling their stories, not mine, leaving readers to make up their own minds.

How do the subjects you followed — one of whom came to hear you speak at M on the Bund in March when I moderated a book launch event for you there — feel about being featured in the book?

I was relieved that none of them felt I had majorly misrepresented them. I was clear with them from the start about the nature of the project, and they were all on board with it, but I didn’t know how they would react to seeing the book in print. A few loved it: Lucifer, an aspiring music star whose story is among the most colorful in the book, has been talking about it to anyone who will listen, and Mia came to the Shanghai literary festival event as you mentioned. Others, like Dahai, don’t have good enough English to read it (so far there isn’t a Chinese edition but fingers crossed that will become possible) yet enjoyed seeing their pictures in the back. A few had small corrections that I’ve addressed in the paperback edition. But on the whole, I was pleasantly surprised that they didn’t mind, even appreciated, some English bloke writing about their lives. Fred, the daughter of a Party official whose opinion I was most nervous about, even wrote a reflection on the book that I translated and published online.

So what first brought you to China, and was it always the plan to pursue writing there?

The best answer I can come up with is “accident.” In the summer of 2007, right after graduating from university with a degree in English lit, I taught English for a summer in a Tibetan mountain village in Qinghai province, an experience I wrote about later in the book of reportage Chinese Characters which you co-edited. Then a year later I came to Beijing to learn Mandarin and sort of … stayed. I always had a vague notion of wanting to be a writer, and from 2008-2010 I wrote a narrative blog called Six, in which I followed (a different) six young people in and around Peking University. I suppose Wish Lanterns grew out of that seed, in a way, and in 2012, after two years in London running literary interviews for the website Five Books, I returned to China and started work on the book. I’ve always freelanced, but I’m the worst kind of journalist: one with literary aspirations.

In addition to working on the book and writing features for various publications, including LARB, of course, you also founded and edited the Anthill. For those who don’t know about it, what exactly is that website and how did it develop and grow?

The Anthill was a “writers’ colony” for anyone with a China story to tell. It focused on narratives rather than opinion and news, and also featured fiction, translations, poetry and photography. I started the site in 2012 and some 120 writers have contributed over 380 posts since then. Some highlights include a memoir of Sichuan during the 2008 earthquake, a family history of the first gaokao exam in 1978, and tales of my own hutong neighbours. In 2015 we put out an anthology, While We’re Here, with Earnshaw Books, and we have also hosted three very boozy storytelling and drinking events at the Beijing Bookworm. It has been a great ride. But now, five years on, the hill is folding into the new LARB China Channel, although the site will remain archived online.

Tell us more about the China Channel, and what work you’ll be doing as Managing Editor of this new venture we’re both involved in? Are there any tips you want to give prospective contributors of the sort of things you’re particularly interested in having them pitch to you?

We’re very excited for the new China Channel, which will launch in the fall. It will be a hub for reviews and commentary on China from a wide network of writers, readers, academics and China hands. The focus will be on the literary, cultural and societal side of China, as befits our LARB umbrella, rather than politics and news analysis for which there are other hubs. We also plan to run translations and a feature on Chinese language, to bring the anglophone and sinophile worlds closer together. I’m looking for contributions that bring to life an aspect or perspective of China that we might otherwise have overlooked, while being accessible and interesting to the merely sinocurious. We have a very talented team, and welcome pitches and questions at larbchinachannel[at]gmail.com.

Switching gears a bit, I’ve been asking everyone I interview for LARB if there is any recent book on China that you wish had gotten more attention? Or if you’d like to tell us to watch for something that you know is in the works, that’s fine, too.

Hmmm. I think there’s lots of homegrown Chinese writing in translation which gets overlooked in favor of China nonfiction by foreigners (ahem). The writings of Murong Xuecun and Yu Hua are a good open sesame, and Running Through Beijing by Xu Zechen, which Megan Shank wrote about for this blog, is a lovely novella that brings the fabric of the capital to life, along with the work of Zhu Wen and Yan Lianke. Also on topic of Chinese citizens talking about their own country, I’m looking forward to Karoline Kan’s forthcoming book about China, including her own personal and family history, which she is working on now.

Same question but with a twist: is there a recent book on China, scholarly or popular, that you wish was getting less attention now, or a past one that you wish did not have as much influence when it came out or such lasting influence now?

For a very long while, the first and possibly only book that Americans and Europeans read about China was The Good Earth by Pearl Buck, who went on to win the Nobel Prize for Literature. It is still read widely today, and back in 2013 I wrote for this blog about reading the book in the same farmlands of Anhui where it is set. It’s not a bad read, quite enjoyable to be honest, but it’s hardly a nuanced portrayal of China, and pretty hackneyed. It also feeds into — perhaps even created — a romanticization of poverty in China that lingers today, combined with notions of overstretching, hubristic Chinese greed that really aren’t helpful.

I’ve also been asking, is there any famous China book or film that you know you really should have spent time with but haven’t been able to bring yourself to actually read or watch?

There are so many. One thing we’re hoping to do on the China Channel is periodically pull out books and films from the shelf that deserve another look, giving them a fresh recommendation. But one that I’m embarrassed to admit I’ve never read is Mao’s Little Red Book. You’d think that for a book of such monumental importance which, like everyone else, I have owned for years and years, I would actually have looked inside the thing. But, you know, I don’t believe I’ve ever bothered to open it a single time. Having it seemed enough, somehow. Sometimes I wonder if many members of the generation who took it as scripture bothered to read the damn thing, either.