The weekend before Thanksgiving was a big one for international headlines. The biggest breaking story, coming out of Geneva, was of a multinational team of negotiators hammering out a nuclear-arms deal with Iran. When John Kerry announced this agreement, American commentators reached quickly for historical analogies, focusing mostly on two years in the last century. Those happy about the agreement likened it to a 1972 diplomatic breakthrough: Nixon’s famous meetings with Mao. Those displeased by it cited a 1938 disaster: Chamberlain’s infamous appeasement of Hitler. Thinking about the news out of Geneva, as well as these polarized reactions to it, I was reminded of a different year: 1979.

Admittedly, that year’s been on my mind a lot throughout 2013, partly because it was a key one for Deng Xiaoping, and new President Xi Jinping has been striving to identify himself in people’s minds with that most powerful of post-Mao Communist Party leaders. I thought of 1979 back in June, for example, when Xi came to the U.S. to meet with Barack Obama in what has become known as the “Shirtsleeves Summit,” since the main photo op that came from the meeting showed the two leaders walking and talking sans coats and ties. As I noted in a commentary for the History News Network at the time, Deng’s 1979 visit to the U.S., the first by a Chinese Communist Party leader, had also included a memorable bit of sartorial symbolism: his donning of a cowboy hat at a Texas rodeo. More generally, in 1979, as he was consolidating his position as China’s paramount leader, three things Deng did was call for a pragmatic approach to development, push for social and economic reforms, and crack down on domestic critics (in that case, those involved in the Democracy Wall Movement). Xi has done these same three things.

There is, though, a quite specific reason that 1979 came to my mind when the news about the Iran deal broke and analogies to both Nixon meeting Mao and Chamberlain giving in to Hitler began to fly: that year began with a January 1 joint declaration by Beijing and Washington proclaiming a full “normalization” of relations between China and the United States. Some Americans hailed this 1979 agreement as an important step toward fostering world peace, but others denounced it as a case of a liberal President doing a dangerous disservice to a valued ally. Complaints from some quarters then that Jimmy Carter had sold out Taiwan parallel closely some that are being heard now from those convinced Obama has done wrong by Israel.

The analogy is not perfect, which is only to be expected—nothing that happens in one century is going to be exactly like something done in the previous one. The Iran deal involves several countries, for example, whereas the 1979 agreement was between just two nations. And Obama’s policy on Iran has broken from that of his Republican predecessor, while Carter’s engagement with China carried forward things that Nixon and Ford had done.

Still, the more I think about the 1979 parallel, the more I’m convinced it is a good one, and a better China-related one than 1972. One reason it seems more useful to look back to the late 1970s than the early 1970s is that when Nixon went to China, he met with a Chinese leader who had been in power for a long time, so the main question about Mao was how much he had changed. Seven years later, by contrast, when the normalization of relations was announced and then Deng came to America, a lot of foreign talk about China focused, as much on Iran does now, on how novel a course a new leader vowing to move in reformist directions would take his country.

1979 analogies seem stronger still if we look at a second international news story that broke right before Thanksgiving: China’s declaration of plans to start monitoring the airspace above and around the islands known as the Diaoyu in Chinese and the Senkaku in Japanese. These specks of land, located near undersea oil reserves, are claimed by both Beijing and Tokyo but have been effectively under Japanese control in recent years. Due to America’s long-term security alliance with Japan, as well as the White House’s commitment to maintaining the status quo where island disputes like this one are concerned, Kerry ended up having a very busy weekend indeed. He needed to follow up his upbeat statement on Iran with a downbeat one on Beijing’s proclamation of a new Air Defense Identification Zone that included the islands, criticizing it as a provocative and inappropriate move. Kerry made these two statements so close together that separate articles on each appeared in the front sections of the same editions of some newspapers.

This simultaneous 2013 reporting of developments suggesting that relations between Washington and Tehran are moving in a positive direction, while tensions between Washington and Beijing rising represents an eerie inversion of the 1979 situation. This is because that year, which began with Beijing and Washington normalizing ties and Deng making a successful state visit to the United States, also witnessed the Iranian Revolution, Ayatollah Khomeini coming to power and denouncing America, and the start of the hostage crisis.

Again, the analogy is not perfect, especially since, thankfully, it is likely that we are seeing just a minor souring of relations between Beijing and Washington right now, not the start of any kind of full-blown crisis. Still, it is relatively rare that stories concerning China and Iran jockey for the attention of the American public at the same moment, and one of the few times this has happened before was back in 1979. A valuable visual reminder of the temporal overlap of China and Iran stories almost three-and-a-half decades ago is provided by the February 12, 1979, cover of TIME. The main headline read “Iran: Now the Power Play,” and the image accompanying it and taking up most of the cover featured a stern looking Khomeini, shown in color, breaking through a giant black-and-white portrait of his own face, symbolizing that he was now a formidable man on the spot, as opposed to a figure in exile who provided a rallying point for opponents of the Shah. Up in the right-hand corner of the cover, though, was a very different smaller headline and smaller image: it referred to Deng’s “triumphant tour” and showed two faces, that of the Chinese leader and that of Carter.

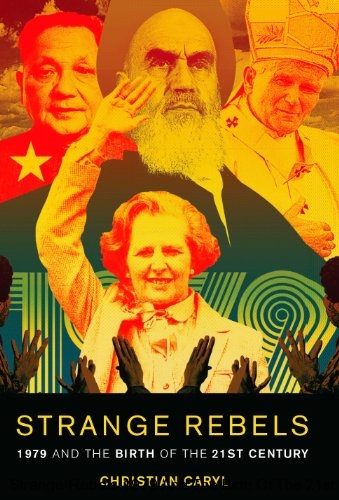

A final 1979 and 2013 note is in order, which has to do with the book whose cover is shown at the top of this post. Early this year, my friend Christina Larson, who used to be an editor at Foreign Policy and is now China correspondent for Bloomberg Businessweek, told me that, given my interest in placing China in comparative perspective and connecting the past to the present, I should be sure to get hold of a forthcoming book by Foreign Policy contributing editor Christian Caryl. Valuing Christina’s judgment, when Christian Caryl’s Strange Rebels: 1979 and the Birth of the Twenty-First Century came out, I made a point of getting a copy. Reading it, I was duly impressed. And even though I’m unwilling to give up on the notion that 1989, with the Tiananmen protests and the fall of the Berlin Wall as well as many other major events, was an even more consequential year than 1979, at moments like this it is well worth remembering just how dramatic that often overlooked earlier decade-closing twelve-month period was.