For well over half-a-century, novelists have been setting tales in 1930s Shanghai, an unusually cosmopolitan city that was divided into foreign-run and Chinese-run districts and known for its bustling port and decadent nightlife. Talented Chinese authors, such as Zhang Ailing (1920-1995) who published in English as Eileen Chang, set stories in the metropolis while the era of the Japanese invasion of China (1932-1945) and eight-year occupation of Shanghai that began in 1937 were underway. A writer now probably best known in the West for writing the stories that inspired the film “Lust, Caution,” Chang was the author of novels such as Half a Lifelong Romance and The Fall of the Pagoda, both set in Shanghai, as well as the translator of Han Bangqing’s The Sing-Song Girls of Shanghai, an older volume that chronicled the city’s red-light district in the late 19th century.

Foreign writers of the 1930s and subsequent periods have been drawn to it as well. Emily Hahn and Vicki Baum were among the novelists from other parts of the world who spent time in and wrote about the city during its most fabled era — though the former was known more for her New Yorker articles and memoirs dealing with Shanghai than for works of fiction set there. More recently, in the 1980s, J.G. Ballard revisited the Shanghai of his youth in Empire of the Sun, whose action begins in 1941. Still closer to the present, the city of the 1930s has served as a backdrop in, for example, Lisa See’s Shanghai Girls, which begins there and then has its lead characters journey to America, and Jennifer Cody Epstein’s The Painter from Shanghai, which tells the story of artist Pan Yuliang, a former teenage prostitute who later studied painting in France and Italy, and who spent the last four decades of her life in Paris.

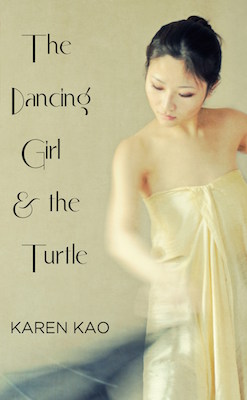

One thing that links several of the novels just mentioned is that they depict the hardships of women and girls. No Old Shanghai novel I know of, however, has gone into the devastating psychological after-effects of sexual assault as deeply as Karen Kao does in her debut novel: The Dancing Girl and the Turtle.

Kao’s novel, recently published by Linen Press, opens with the brutal rape of Song Anyi, an educated young woman from Suzhou who was en route to nearby Shanghai after her parents both passed away. Her older brother, Song Kang, had lived in Shanghai for some years before moving to Ohio for his studies. Before he left for America, Kang frequently wrote his sister long letters from Shanghai enthusing about its attractions. These let to her desire to move to the big city, where their aunt, uncle, and favorite cousin, Song Cho, lived. When Anyi set out for Shanghai, she had no reason to think her relatives wouldn’t take her in. But when she finally arrived at their front door—after her attack—she was barely alive. According to the customs of the times, her attackers had rendered her a broken woman with no chance of a normal marriage.

Kao takes the reader into the mind of Anyi after her cousin Song Cho nursed her back to what appeared to be a full recovery. Before Anyi moved in with the Song relatives, Cho had been a partying, opium-smoking womanizer, but that all changed as he stayed home to take care of Anyi.

As in many novels set in 1930s Shanghai, as well as in periods just before and just after that one, the upper crust Song family employ a slew of servants, from a cook to a driver to a housekeeper and various maids. The story is told through the first person perspectives of Anyi and Cho, but also through the third person viewpoints of two of the Song family’s maids, Blossom and Nian. The Japanese political attaché, Tanizaki, is a pivotal character in the story as well. When the book treats the decline of the Song family and the lead up to the 1937 Fall of Shanghai, his third person viewpoint is also included.

Cho and the maid, Blossom, have a thing going before Anyi comes onto the scene. When Blossom sees that she’s been replaced by the beautiful and Anyi, the maid deceitfully introduces Anyi to Auntie Wen, a blind masseuse who is brought in to help heal her external wounds. What the Song family doesn’t know is that Auntie Wen is a devious woman who sells women and girls into the most violent echelons of prostitution. Blossom knows this and it’s her malicious way of getting Cho to divert his attention from Anyi back to her.

This is where Kao’s novel overlaps with The Sing-Song Girls of Shanghai, which focuses on unsuspecting peasant girls and other outsiders being swindled into prostitution. Han Bangqing’s novel goes into great detail regarding Shanghai’s red light district, the women who work there, and the men who patronize it. Where Kao’s work differs is through Anyi’s self-destructive path to end the psychological pain from her rape. Although post-traumatic stress disorder wasn’t coined until four decades after this story takes place, Anyi demonstrates all the symptoms of what we now know as PTSD. Her recurring nightmares of her attack, her visions of her attackers (they were soldiers and there was more than one), and the spirit of her dead parents visit her on a daily basis. She submits to the sadistic men procured by Auntie Wen because she just wants to end it all. Cho tries to save Anyi and wants to marry her, but she’s unable to form a healthy relationship when her demons haunt her day and night.

Kao’s attention to detail is meticulous and it is obvious she has researched the unique characteristics of 1930s Shanghai, handling well such details as the way Mexican silver dollars functioned as the preferred local currency and the presence of Jews in Shanghai (the novel takes place just before the massive influx of Jewish refugees from 1937 to 1941). Parts of her story are set at the city’s premier hotels: the Cathay, the Palace, and the Park.

One plot point, though, stood out to me as a missed step in terms of historical context. Kao writes about the relationship between two first cousins—Anyi and Cho—as though it were unnatural or at least odd. Back in the 1930s, however, that kind of liaison was quite ordinary and it wasn’t looked down upon. My own cousin from Shanghai (a German Jewish refugee) sailed for the United States after the war because his first cousin—and future wife—sponsored his immigration application. Back then, many of my family members were married first cousins, and this Shanghai relative originally had his eyes set on another first cousin, but settled for her sister.

The Dancing Girl and the Turtle is a remarkable, character-driven debut, which tells a powerful story against a well-known urban backdrop. The reader will remember Song Anyi and her terrors long after the last page is turned.