By Paul French

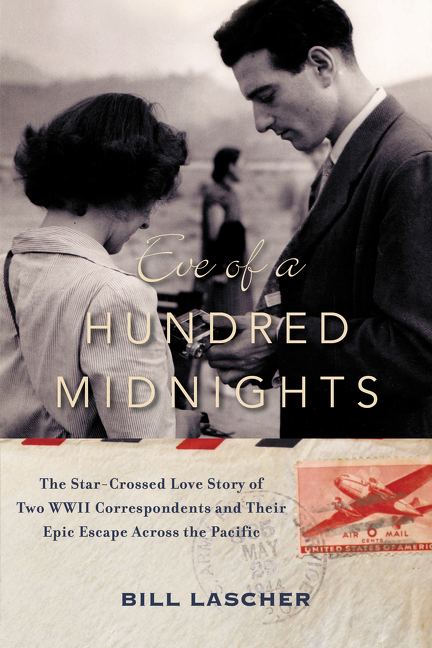

Bill Lascher is an Oregon-based journalist who didn’t realise he was related to one of the great journalists of the China Press Corps in World War Two, Melville Jacoby. Lascher set out to write a dual biography of his cousin and Mel’s wife — and fellow China correspondent — Annalee Jacoby. Before World War Two Melville Jacoby had found himself in China and ended up in journalism by a round about way (all explained by Lascher in his new biography of the couple, Eve of a Hundred Midnights: The Star-Crossed Love Story of Two WWII Correspondents and Their Escape Across the Pacific, which was published earlier this year). Annalee (then surnamed Whitmore) had tired of working as a scriptwriter in Hollywood and found herself in China, too.

Both got to know each other as China was invaded by Japan. Despite initially agreeing with New Yorker writer Emily Hahn that Jacoby was “arrogant,” Annalee eventually agreed to marry Melville (always known to family and friends as “Mel”) as he was off to Manila while she stayed in China and worked for the United China Relief organisation. Later, in 1943, Annalee worked in the wartime capital of Chongqing eventually co-authoring (with Theodore “Teddy” White) the classic war reportage book Thunder Out of China, which remains in print a full seventy years after its initial publication in the fall of 1946. Both Mel and Annalee were excellent journalists who built close relationships with China, the foreign press corps in the country during World War Two, and, of course, each other.

Mel and Annalee certainly deserved a biography but producing one required a lot of detailed knowledge of China at perhaps its most complex historical point, that of the Second Sino-Japanese War, as well as an ability to evaluate the couple’s role among the foreign press corps of China, their assumptions and interpretations of China during the war and their own foibles and failings. The author of such a work would also have to deal with the fact that neither Mel nor Annalee (unlike, say, the also for a time China-based Ernest Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn, who were even the subjects of a 2012 HBO biopic) are household name these days, even among China historians. So not an easy proposition – particularly when you’re related to the subjects. Yet Bill Lascher’s Eve of a Hundred Midnights has received universally excellent reviews and recommendations. Time to talk to the author….

PAUL FRENCH: So you’re Mel Jacoby’s cousin? And your grandma gave you Mel’s Corona 4 portable typewriter, but you’d never heard of him? Are you now thoroughly ashamed of yourself and did you decide to write Eve of a Hundred Midnights as recompense?

BILL LASCHER: Ha! I’m not so much ashamed of myself as disappointed. I feel like I would have had a wonderful time with this information when I was an undergrad (at Oberlin in Ohio). I was already passionate about journalism and media history. I can only imagine what I might have done with my studies, and my ensuing career, had I known about Mel back then. I certainly might have dodged a great deal of professional uncertainty. On the other hand, I may not have fully appreciated Mel’s story then, and, perhaps, may not have given this book the care it deserved. But, yes, once I knew Mel’s story I knew I had to do it justice.

Would it be fair to say you really knew nothing of China and its modern history before starting on the book? We can now assume after reading Eve of a Hundred Midnights that you are what the Americans call a “quick study”?

Yes. I’d say that’s a fair statement. “Nothing” might be a little strong, but I don’t think I knew much more about China than anyone who paid a little attention to world history or international affairs. I do have a brother who lived in China for a while and who speaks fluent Mandarin, so for a long time he (along with an aunt of ours) has been better-versed on the country. Indeed, I might now have more of an academic understanding of China’s wartime history, but I’d still say he understands present-day China far better than I do.

Even if I understand Chinese history better than I did when I started working on the book, I try not to claim to have a better grasp on the subject than those who have long studied the country, let alone Chinese nationals or émigrés. Still, I strived to remedy my lack of knowledge while working on Eve of a Hundred Midnights. As I researched the book, I crash-coursed works on China, particularly 1930s-40s China. Fortunately, I’ve been aided by the voluminous work of Mel and his contemporaries — such as Annalee and Teddy White – as well as some recent scholarship on that era (Rana Mitter’s 2013 Forgotten Ally: China’s War With Japan 1937-45 is one such example). Also, people such as yourself have generously answered questions I’ve had as I’ve proceeded with my research.

One important note: all of this is true for China, but a significant part of this story involves the Philippines, and I was even more poorly-versed in that country’s history and culture than I was in China’s. However, I’ve had similar assistance from people who studied the Philippines or were from there. Manolo Quezon, a former undersecretary of communications and the adopted grandson of Manuel Quezon, the country’s 1st president, was one who stands out, and Liana Romulo, granddaughter of Carlos Romulo, who befriended Mel and Annalee during their stay on Corregidor, was another. I even had help with Macao, which played an early but important role in Mel’s experience of Asia, from a scholar named Roy Xavier, and some attempt to add perspective on journalism in China and the field’s history from the Foreign Correspondents Club of Hong Kong, particularly the photographer Carsten Schael. In every case, even if some of these people couldn’t answer questions for me directly, they often pointed me in the direction of resources that helped.

I used to have a theory — that you’ve blown — that biographies written by family members were always awful as the author couldn’t (or rather perhaps wouldn’t) distance themselves enough from the subject to see the potential bad sides and poor character traits that we all possess. It’s led to a lot of bad, or at least largely pointless, biographies, yet you seem to have avoided this. How?

I tried tremendously hard.

Yours is a good theory, and I think I share some of the same scepticism. This entire endeavour pivots on the fact that I learned about Mel when my grandmother gave me Mel’s typewriter and began telling me his extraordinary story. What better gift could one receive? But what a responsibility came with it. I couldn’t just write “I’m related to this guy, wasn’t he cool?” If I wanted my book to be read and Mel to be understood, I had to write it well. I had to make the most of this incredible opportunity.

That meant taking excruciating care to source the book. It had to be credible, and to be so, I felt I had to be certain that what I was writing about actually happened. I had to be sceptical because I knew readers would be.

Mel would have fascinated me even if we didn’t have a personal connection, but if I had lionized him in this book, he wouldn’t feel real. I didn’t want to go easy on him. I didn’t want to portray him shallowly. So I tried doubly-hard to research sources beyond Mel’s own papers and those of people who loved him. I wanted to find as much as I could that others had said or written about Mel, and I wanted to know what private reflections people outside of Mel’s family had of him. Writing fairly about Mel was the best way I could pay tribute to him. Accuracy mattered tremendously to him. He was frustrated when he found out how his reports were inflated or conflated by editors back home, so what justice would I be doing to him if I cut corners in this book?

It’s certainly possible that I’ve missed some sources — one of the aggravating aspects of research, particularly when dealing with a subject where most of the principles who could guide your inquiries are dead, is the lingering feeling that there’s always more material out there beyond what you’ve found.

I also have my literary agent — Jessica Papin, of Dystel & Goderich Literary Management — to thank for some of my approach. Jessica spent more than a year trying to sell the proposal that eventually became Eve of a Hundred Midnights before Morrow acquired it. With a keen editorial eye, she guided multiple revisions of the proposal until Morrow and two other publishers wanted it. A significant part of those revisions involved fleshing Mel out more fully, urging me to dig deeper to describe him more realistically. After the book was acquired, Henry Ferris, my editor at Morrow [n.b. publisher of the U.K. edition of the work], and his equally-insightful assistant, Nick Amphlett, further prodded me to better ground both Mel and Annalee. I think the book is better (and more accurate) for the suggestions from all three, as well as those that came from a select few others who read my drafts.

A few people (including me) have told parts of the story of Mel and Annalee Jacoby before — Teddy White called Mel, “one of the greatest US war correspondents,” but his career in China and covering the war was kind of accidental wasn’t it?

I’m actually not so sure I’d call it accidental, unless we argue that everyone’s career is accidental. For example, Teddy’s career might seem just as accidental. Yes, Teddy studied China at Harvard, but journalism came later to him. Conversely, Mel was interested in journalism first. His interest in reporting reaches back to his grammar school days. On the other hand, China came after his exchange year at Lingnan, at what is now Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou. Mel’s career was no more accidental than Teddy’s was. Aren’t we all products of either the opportunities we’re presented, or those that are denied to us?

It’s a touch clichéd to say we make our own luck, but what I think matters is that Mel made the most of his opportunities in China, the Philippines, and elsewhere. For example, in August of 1940, Mel left Chongqing for French Indochina (contemporary Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia). After France surrendered to the Nazis, Mel knew that Japan’s coziness with Germany meant the surrender had implications for Asia. Japan was trying to cut off supply lines to China that went right through France’s colony.

Mel rightly guessed that Indochina had become the place to be as a reporter covering the war in Asia, so he decided to go to Hanoi on his way back home to the U.S. He originally planned to stay for just a few weeks. Instead, he remained for three months, earning himself a gig as a stringer for the UP (and also tails and execution attempts from agents of Japanese puppet Wang Jing-wei after Mel and diplomat Robert Rinden were arrested by Japanese soldiers). In turn, Mel’s work earned invitations from the UP to work in other capacities, as well as assignments from other publications based on the reporting he’d done in Southeast Asia.

By the time Mel returned to China the following year and was hired by Time (yes, after a somewhat coincidental encounter with Henry Luce), he did so with the confidence he’d have other opportunities if that work didn’t pan out. Mel did regularly encounter larger-than-life figures — the Soong sisters, Chiang Kai-shek, Teddy White, Henry Luce, Manuel Quezon and Douglas MacArthur — and, at first, I thought the key to this book was that he always seemed to be around these amazing and unbelievable situations. Then, as I dug deeper, I realized that chance played a role, but Mel was in such close proximity to these pivotal people and events because he’d made choices that put him in their orbits.

Ultimately what mattered for Mel and his career is how he developed his interest in China, returned to the U.S. newly-devoted to that interest and to fusing it with his interest in journalism, how he decided to return to Asia (twice), and his commitment to reporting on the war even when other pressures — joining the military, safe job opportunities on the homefront, seeing his family, falling in love — weighed on him. Again, I don’t think that’s terribly different from how any of us decide to take next steps in our studies, our careers, or our lives.

Recently I talked about Helen Foster Snow with an actress playing her on TV. We discussed how the overpowering myth of Edgar Snow has rather obscured and shadowed Helen despite her being (in my opinion) the far better journalist and writer of the couple. Setting aside that Mel’s your cousin (and so you’re forgiven a little partisanship), wasn’t the same true for Annalee back in WW2?

I think it was, though Mel did his part to get Annalee her due. He briefly toyed with suggesting she replace him doing radio broadcasts from Chongqing’s XGOY (though that didn’t last since they wanted to reunite) and once he left Manila, he urged Time to look to her for reports. He also made sure the publication knew which reporting was hers from the work they did together on Corregidor and on the run from the Philippines.

Still, one of the more nefarious aspects of systemic sexism is that much of it is unconscious. People regular referred to Annalee as Mel’s wife, as a sort of supporting actress in his story. One example of where you can hear this is in an episode of March of Time, the weekly documentary radio series, about the dramatic journey Mel and Annalee took escaping from the Philippines. This series used dramatic recreations of news events, rather than directly recording the subjects themselves, and that particular episode depicted Annalee as much more of a simpering damsel than she actually was. It was as if the writers couldn’t imagine Annalee having agency of her own. Also, Annalee’s sidelining didn’t end at her association with Mel. I couldn’t begin to tell you how many times I’ve heard the phrase “Teddy White’s book Thunder Out of China” when it was just as much Annalee Jacoby’s book as it was White’s. That many more associate this bestseller with its male co-author than the female half of the equation speaks volumes.

As to who was the better journalist, well, it’s harder to assess Mel’s career. I don’t want to spoil the book too much, but whereas the Snows each had decades to distinguish themselves, I think it’s fair to say Mel didn’t quite have the opportunity to make his mark in the profession or build a body of work that they or Annalee did.

You rightly dwell on the wartime capital of Chongqing where both Mel and Annalee reported from — it’s been an underwritten about place at that time. Annalee and Teddy White wrote, “Chungking is marked on no man’s map … Men great and small, noble and corrupt, brave and cowardly, convened there for a brief moment; they are all gone home now.” It seems the city left its mark on both of them — a very special place at a very special time right?

It sure did. Chongqing also left its mark on me, both in the form of the city as it was viewed by Mel, Annalee, Teddy, Carl & Shelley Mydans, and their contemporaries, and in its present form. I visited Chongqing in March 2015, while I was still writing the first draft of Eve of a Hundred Midnights. I was entranced and vexed by Chongqing, an impression I think I share with others who visit the city. It was an uncanny visit, too, as I arrived in Chongqing at the tail end of China’s Spring Festival.

One night, I was atop Liangjiang Pavilion, a viewing platform above hilltop Eling Park with 360 degree views of the city. That afternoon I’d visited the Three Gorges Museum, whose exhibit on the war includes a dramatic multimedia recreation of the intense air raids that pummeled Chongqing (In vivid detail for Life, Mel wrote about the worst of these, a June 5, 1941 catastrophe during which thousands died in ensuing stampedes). Bathed in the glow of the pavilion’s red lights, I watched fireworks boom here and there above the city, while the staccato of firecrackers rattled unseen in the dark alleys I knew spread beneath. Chongqing is a city of hills in all directions, a topography that amplified these fireworks’ echoing blasts. Though that night was celebratory, I could only think of the war, of what Mel and Annalee and the half-a-million terrified people who moved to Chungking during the conflict must have heard.

It’s true that I was probably looking for symbolism in Chongqing as I searched for Mel’s footsteps. I was hungry for meaning, for connection, for a reason to be there, alone, thousands of miles from home. Still, aside from what I may have been looking for, there’s a certain magic in the city. There’s this constant flow between noise and peace that pervades life in Chongqing. It’s such a crowded city, yet any time you turn a corner you may stumble into an oasis of calm, perhaps an apartment stoop lined with leafy greens set out to dry, a hidden park where it feels like time has stopped, or maybe just a quiet riverside bench on a pathway beneath an expressway. Modernity is quickly burying Chongqing, yet for those who look close enough, layers of the city’s history still exist beneath the Samsung ads and glass apartment towers like strata in a geologist’s model.

I was only in China for a lamentably few weeks, so I can’t claim much understanding of the country as it exists today. Yet based on that experience and from everything I’ve heard since, or discussed with those who remain, Chongqing still stands out as very much its own place in a way that other Chinese cities didn’t quite do for me.

I realize your question was more about the way Chongqing lingered in my subjects’ imagination than my own. I wonder whether I would have had as much of a fascination with the city, if I’d ever had paid it as much heed, had it not had such a hold on Mel. I return over and over again to “Unheavenly City,” an unpublished article about Chongqing Mel wrote (one of quite a few unpublished works that I desperately think deserve publication). One passage strikes me in particular:

“…Americans, Britons, and other foreigners would rather be uncomfortable in Generalissimo Chiang Kai-Shek’s wartime capital fifteen hundred miles from the China coast than any other place in China. No, they wouldn’t admit it. Not in Chungking anyway. They talk about Shanghai night life, think nostalgically of easy-going old Peking, and long for a gimlet at the swank Hong Kong hotel. Boarding a giant Douglas, which miraculously slips out of soupy fogs onto Chungking’s Yangtze river airport, the same people head for the China coast and vacation. For days before leaving the capital city they are in a jittery state of excitement, making the rounds of farewell parties and saying that they will never come back. So great was one correspondent’s anticipation of leaving that he ran a hundred and two temperature for three days before flying out. A week in Hong Kong and he cabled his head office to send him right back to Chungking.

Few foreigners desert Chungking without wanting to return. The set formula is to tell friends in Hong Kong what a hell-hole they are missing, and then to rush right back on the next plane loaded with only thirty pounds of clothes and bare essentials.”

It seems like an age has passed since we first communicated about Mel and Annalee — this really was a labor of love? And what’s next, got the China bug still?

I do have a bit of the China bug. That’s funny, because I started this book I would have thought the brother I mentioned previously was the only family member afflicted with the bug, and the fact I have it now reminds me how much I used to emulate his interests when I was a kid (to his annoyance). I started learning Mandarin this year — though that’s slacked a bit — and I hope to travel to China within the next two years, perhaps when New Star Press releases the Mandarin translation of Eve of a Hundred Midnights, as it plans to do within the next 18 months.

Anyhow, I’d definitely like to write more about this era, both in China, in the Pacific more broadly, and in journalism. Whether the adventurer-turned-journalist-turned-propagandist-turned-celebrity-photographer Earl Leaf, the unique and tight-knit community that lived at the Chungking Press Hostel, the often-overlooked role of French Indochina in World War II, or the glamorous circles Mel rubbed elbows with in Macau, I have a number of tangential article ideas. As I mentioned earlier, I’d love to recreate the journey Mel and Annalee took when they escaped the Philippines. I’m also toying with an idea around a hypothesis of mine that the year 1937 was an unusually influential one in world history.

There are also ideas that have nothing to do with Mel or this time period. Before I started working on this book full-time I was developing an interest in natural disasters and how they impact society, and I have an idea on the history of disasters and our responses to them cooking. I might also return to reporting on transportation and changing cultural perceptions of transportation and infrastructure, which was a key part of my graduate work.

Oh, and pinball. There’s a book out there about the game of pinball, and I think I’ll be the one to find it. That’s how I justify recently joining a competitive pinball league, at least.