By Susan Blumberg-Kason

When I lived in Hong Kong in the 1990s, my only interaction with the police occurred when I’d return from Shenzhen by foot. Once on the Hong Kong side of the Lo Wu Bridge, I always breathed a sigh of relief when I saw their crisp navy uniforms. The sight represented stability, order, and safety, things that were in short supply in Shenzhen and the parts of Hubei that I often visited as well on my forays to the mainland. Life in those places had a Wild West, free-for-all feel to them. There, as opposed to in rule-honoring Hong Kong, the trend often seemed to be that those with guanxi (personal connections) could work the system, while others were left to their own devices.

What I knew about the then-Royal Hong Kong Police Force came mainly from movies. Hong Kong police films were a lot like classic John Wayne westerns, focusing on struggles between good guys and bad guys, with little ambiguity about which were which. At the end there was always a shootout and the good guys prevailed, but not before lives were lost and the viewer sensed that the heroes had not only saved the day, but humanity itself.

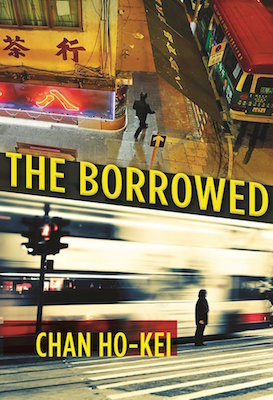

A couple months ago I was excited to hear about the forthcoming English translation of Chan Ho-Kei’s Hong Kong-set police novel, The Borrowed (Grove, 2017), especially since it promised to take readers from 1967 to 2013, thus covering the a dramatic period in the city’s history. (The Chinese original was published in early 2014, just months before the Umbrella Movement and another chapter in Hong Kong political story began.) There are relatively few English language novels set in Hong Kong, and this was one of the first Chinese ones to be translated into English. I imagined The Borrowed would resemble John Burdett’s The Last Six Million Seconds (William Morrow, 1997) a Handover thriller, or the William Marshall Yellowthread Street mysteries set in a fictional part of Hong Kong. Or that it might be a sort of Hong Kong counterpart to Qiu Xiaolong’s Inspector Chen mysteries that take place in Shanghai.

The Borrowed differs from all of these, though, in that it reads less like a single book than like a series of novellas, with the chapters arranged in reverse chronological order, starting in 2013 and ending in 1967. The title refers to Hong Kong’s pre-Handover status as a borrowed place living on borrowed time, and each chapter features Police Superintendent Kwan Chun-dok, aka the “Eye of Heaven,” as he was known around the force. Nothing got past Kwan, not even on his deathbed in Chapter One. He joined the Royal Hong Kong Police Force in the 1960s and was one of a select few local officers sent to England for a couple years in the 1970s for further training.

While the book drew me in from the start, the first two chapters seemed less hard-boiled cop tales and more social commentaries on topics such as Hong Kong’s growing income disparity and capricious entertainment industry. SARS was mentioned briefly in Chapter Two to give it historical context, but overall the opening sections of The Borrowed provided a clean and tidy account of two example of Superintendent Kwan’s almost superhuman pursuit of justice. I wasn’t unhappy with the book when I finished those opening chapters, and figured it would be a retrospective of Hong Kong’s modern history in the guise of tame police stories. Perhaps, I thought, I was naïve to have thought it would resemble the Hong Kong police movies I grew to appreciate in the 1990s.

But then everything changed.

It’s 1997 in Chapter Three, just before the Handover, and a wave of acid attacks on random pedestrians threatens to unravel the usually peaceful lives of Hong Kong residents. Two attacks at a Mongkok outdoor market—one of the densest places on the planet—are followed by another attack in Central, the city’s financial district and administrative hub, also at an outdoor market. On the same day of the latest acid attack, convicted murderer, Shek Boon-tim, escapes from a hospital on Hong Kong Island where he has been taken for acute abdominal pain. Kwan, though about to retire, can’t pass up this case. As Chan writes, “Kwan Chun-dok froze at this name. Eight years previously, on his very first day in the CIB, he’d been roped into an operation against the Shek brothers, Boon-tim and Boon-sing, who’d occupied the first and second places on the Most Wanted list that year.” The younger Shek brother died in that operation, as is detailed in the following chapter, but the older Shek was arrested and the person responsible for that was Kwan

The 1997 section is the prelude to Chan’s most chilling chapter of all, which is set during the 1989 wave of violent crime that fell on the eve of the June 4th Massacre up north in Beijing that ended a massive wave of protests centered at Tiananmen Square. Since the shootout with the Shek brothers was referenced in the previous chapter, the reader has an intimation of what’s in store in this one. The action in the 1989 chapter unfolds like the plot of a Hong Kong police movie made by John Woo, Tsui Hark, or Johnnie To. As in many Hong Kong films, technology plays a supporting role in the story. Chan explains that pagers back in the late 1980s used number codes, so people memorized and communicated through these codes. In late spring of 1989, through code interception, the police learn the Shek brothers are camping out in Mongkok at the Ka Fai Mansions, “an eighteen-story building with thirty apartments on each floor. At one point it attracted quite a few middle-class families, but from the 1970s, development moved away from the area and the building started showing signs of age. About three-tenths of the apartments were now put to non-residential use, from tailors’ shops, traditional medicine clinics, hair salons and trading companies to nursing homes and even Buddhist temples. There were also massage parlours, various clubs and associations, small-scale hotels and one-woman brothels—none of which were particularly good for public order. A place like this was a nightmare for the police.”

From the description of this bleak structure, the sense of impending doom is palpable and the scene is set for a police stake out involving uncover work at a Chinese take-out on the ground floor, ending up at the Ocean Hotel on the ninth floor, “a small and seedy budget establishment.” The ensuing events reminded me of the best Hong Kong noir movies in which the viewer is left feeling exhausted yet relieved by the time the credits roll. One Shek brother is killed and the other gets away, and although the reader already knows that from the previous chapter, it doesn’t make the story any less thrilling.

The carnage affects more than just the one Shek brother, two accomplices, and some police officers. The building residents who get caught in the crossfire “were quickly turned into cautionary tales for teachers and parents to warn children about. Rationally, they must have been aware that these deaths had nothing to do with the deceased’s professions, but the Chinese love stories of retribution. ‘Dishonourable deeds destroy the doer,’ the saying went, so they must have deserved their grisly fate. Like executed corpses displayed before the public, the bodies were now fuel for tabloid moralizing.” This passage is an example of how Chan demonstrates empathy for the average Hong Kong person, rendering him a champion of the people, just as he makes out his hero, Kwan, to be in these stories.

The last two chapters were almost as thrilling. One is set in 1977 and involves the kidnapped school-aged son of a British officer in the Independent Commission Against Corruption (ICAC), founded in 1974 to root out dirty cops and other crooked government officials. The last chapter takes place during the 1967 riots, linked to the upheavals of the Cultural Revolution on the mainland, and is cleverly crafted that I didn’t know the identity of the characters—even though I’d already encountered them in previous chapters—until the very end. Chan’s structure at first glance seems odd. But during the last chapter—written in first person instead of third person, as were the others—it suddenly makes sense.

In the afterword, Chan likens the Hong Kong police of his youth in the 1970s and 1980s to American superheroes. I compared them to the heroes of Westerns, but the idea is the same. They were larger than life and enjoyed a good deal of respect throughout the period of British colonial rule, in spite of some important problems. Before the 1970s, for example, the leadership of the Hong Kong police was mainly white British expats, with locals serving only in lower positions, and corruption within the force was commonplace. That changed in the 1970s and the police force Chan admired as a child appeared very different, with figures not unlike the imaginary Kwan in top positions. Although The Borrowed was published in early 2014, before the police lost credibility during the Umbrella Movement, Chan states in the Afterword that public perception of the Hong Kong Police Force had already started dropping in 2012, a year marked by mass demonstrations against a national education proposal and the inauguration of the now widely disliked Chief Executive C.Y. Leung. As Chan writes: “Hong Kong today is in just as strange a state as in 1967. We’ve come full circle, back to the beginning.”