We started with a simple plan. We’d get six people to suggesting a pair of books apiece, making a dozen in all — maybe a baker’s dozen, if one person couldn’t resist slipping in a third title. In the holiday spirit of excess, though, things got out of hand. As three of the four core members of the old China Beat team came together to make their suggestions, we couldn’t resist seeing if the final member of the quartet, Kenneth Pomeranz, would chime in too. Only one of us managed to limit ourselves to two titles.

Anyway, here’s the list which, combined with last week’s, is now well beyond a dozen, baker’s or otherwise:

Kate Merkel-Hess

@kmerkelhess

The Three-Body Problem, by Cixin Liu

This is the 2014 Ken Liu translation of a 2008 book that was a bestseller in China and stands out as a prime example of the country’s lively science fiction genre. It is classic SF — multi-page tangents on math, physics, and technology dot the text, and crucial components of the book take place in a virtual online world — but it is the context, and its presentation, that I found so stunning. The book, the opening installment of a trilogy, toggles between the stories of secret scientific installations during the Cultural Revolution and the present day, and while the Cultural Revolution is key to the set up, the politics of the period are never the point of the book itself. Liu, like many sci-fi writers, creates stories where the vastness of space and (mini spoiler!) encounters with alien life raise questions about our shared humanity and what it means. But in the science fiction that most Western readers are familiar with, those encounters take place against a Western backdrop. The Three-Body Problem neatly displaces us, while, indeed, successfully demonstrating the universality of appealing sci-fi themes and questions. For those who get hooked, the second Three-Body Trilogy book is available in English (it came out last summer as The Dark Forest, with Joel Martinsen doing the translation) and the third, Death’s End, is slated to be published in 2016 (with Liu back as the translator).

In Manchuria: A Village Called Wasteland and the Transformation of Rural China, by Michael Meyer

When I was in college in the late 1990s I spent a semester studying Chinese in Manchuria, so I was looking forward to Michael Meyer’s new book, which chronicles his time living in a little village in Manchuria called Wasteland. The book is part love story, part ethnography, and part history. Meyer ends up in Wasteland because it is the hometown of his wife, Frances, but for much of the book she is working as a lawyer in Hong Kong, only visiting infrequently, as Meyer navigates the sometimes-confounding social dynamics of a close-knit village.

Interwoven with Meyer’s stories of life in Wasteland and his reflections on the changing nature of rural China are his investigations of the rich history of Manchuria. As he shows, a place that many readers will probably initially view as a backwater has actually been a critical crossroads in some of the modern world’s most important stories. Meyer is also the author of the well received 2008 book The Last Days of Old Beijing: Life in the Vanishing Backstreets of a City Transformed, and taken together, the two volumes demonstrate his fascination with the way that the past is entwined with present and future. For a historian, that’s a comforting and natural way of looking at the world, but in the hands of a storyteller like Meyer it is also evocative and moving, a reminder of the way we live with the past and also change it.

Flood of Fire, by Amitav Ghosh

Land Bargains and Chinese Capitalism: The Politics of Property Rights Under Reform, by Meg Rithmire

Quest for Power: European Imperialism and the Making of Chinese Statecraft, by Stephen Halsey

Anxious Wealth: Money and Morality Among China’s New Rich, by John Osburg

There’s an embarrassment of riches to choose from, but my first choice is almost too easy: Amitav Ghosh’s superb Flood of Fire. As a novel, it’s completely engrossing; as a history of the 19th century opium trade, it’s remarkably accurate and comprehensive; as a vivid reminder of the human dimensions of those events, and the fact that the participants cannot be reduced to just victims and villains (or just Britons and Chinese), it is unsurpassed. You can read it without having read the first two books in Ghosh’s Ibis trilogy, but if this gets you to read them, so much the better.

For highly readable and important academic work on China, three new or at least newish works by younger scholars come to mind. First, Stephen Halsey’s Quest for Power: European Imperialism and the Making of Chinese Statecraft reminds us that for all the battering China took in the late 19th century, it was never formally colonized. Building on lots of other recent scholarship, Halsey shows that the last decades of China’s final dynasty, the Qing — sometimes written off as a long succession of failures — should instead be seen as an important period of innovation in Chinese statecraft, resulting in a military-fiscal state with many resemblances to those of early modern Europe. Of course, the dynasty ultimately fell anyway, but Halsey shows that the influence of its efforts lingers: among other things, in a distinctive understanding of sovereignty, which colors Beijing’s internal and external policies even today.

My other two books should particularly interest those who want a deeper understanding of the contemporary Chinese economy, and sense that economics alone won’t provide it. John Osburg’s Anxious Wealth: Money and Morality Among China’s New Rich is an excellent ethnography of elite businessmen (and a few women) in Chengdu. Osburg focuses on the endless “night work” of these entrepreneurs: the entertaining of customers, suppliers and other contacts without which they could not succeed. The book shows vividly how connections are made through providing others with drinks, parties, and sometimes women; how those connections matter, and why it’s too simple to call it all “corruption.” You also hear the participants in this world, both men and women, reflect on the toll this system takes, what “merit” and “competition” mean within it, and how they might like to see things change, both in their own lives and in Chinese society.

Meanwhile, to see how one very important feature of China’s economy came to have its distinctive shape, read Meg Rithmire’s Land Bargains and Chinese Capitalism: The Politics of Property Rights Under Reform. (This one is brand new, and I confess I haven’t read all of it yet myself.) Excepting a few petro-states, China today is almost unique in the degree to which government relies on revenue from state-owned assets, rather than taxes on private transaction; the biggest single such asset is the land itself, which can be leased for long periods, but not privately owned. This often-overlooked fact shapes Chinese development in many, many ways, and Rithmire provides an eye-opening account of the evolution and implications of land policy in three big Chinese cities, from the onset of reform in 1978 forward.

Maura Cunningham

@mauracunningham

Spy Games, by Adam Brookes

Dragon Day, by Ellie McEnroe

The Coroner’s Lunch, by Colin Cotterill

There’s nothing more satisfying than settling in at the end of a dark winter day with a hot cup of cocoa (or something stronger) and a thick spy thriller. Help someone in your life realize this by giving them two or three juicy volumes to enjoy while the snow falls outside and the fire roars. I recommend the latest offerings by Adam Brookes and Lisa Brackmann, who both write compelling spy novels with a China twist — though their books should be of interest to anyone who enjoys a good thriller, regardless of their level of China knowledge.

I reviewed both recent books in previous posts for the China Blog: Brookes’s engrossing Spy Games (reviewed here) continues the story of world-weary journalist Philip Mangan and his international exploits, while Brackmann wrapped up her phenomenal Ellie McEnroe trilogy with Dragon Day (reviewed here). To ensure that your gift recipient gets the full arc of both stories, bundle the new books with copies of their preceding ones — Night Heron (Brookes) and Rock Paper Tiger and Hour of the Rat (Brackmann).

I’ve got one more suggestion, which stays in Asia but is not China-focused and came out some time ago, though I only recently discovered it: The Coroner’s Lunch, by Colin Cotterill. I just finished reading this first book in a 10-volume series, which is set in Laos in 1976 and follows the adventures of Dr. Siri Paiboun, a 70-something reluctant coroner with a wry sense of humor. With nine more books to go in Cotterill’s series, my winter reading list is set.

Jeffrey Wasserstrom

@jwasser

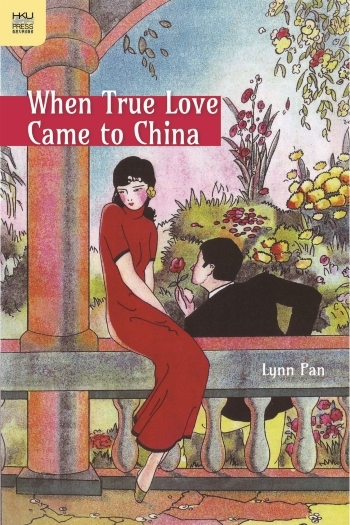

When True Love Came to China, by Lynn Pan

The Sacred Routes of Uyghur History, by Rian Thum

The Love of Strangers: What Six Muslim Students Learned in Jane Austen’s London, by Nile Green

My first reading suggestion is Lynn Pan’s extraordinary When True Love Came to China, which is available in Asia now and will be out in other markets this spring. Pankaj Mishra singled it out in the Guardian as one of his books of the year, describing it as “a rich and gripping account of how the first generation of modern Chinese intellectuals and writers discovered the pleasures — and sufferings — of romantic love.”

I’ll also let someone else tell you what is so good about my second selection, Rian Thum’s The Sacred Routes of Uyghur History, a beautifully crafted work. In his review of the book for this publication, Central Asianist Nile Green writes that while Thum’s book offers much to the reader seeking a better understanding of contemporary problems in Xinjiang, at its “core it is not political study” and goes beyond “the familiar ideologies of modern times toward older ways of knowing and belonging.” The result he says is a “humanist project” of “empathy and magnitude” which explores “the experience of the past in a society few have tried to understand in its own terms.”

Following some of my colleagues in slipping in extra works and moving beyond books that focus on China, I’ll close with a shout out for Green’s own new book, The Love of Strangers: What Six Muslim Students Learned in Jane Austen’s London. Original in format and gracefully written, it could be described with many of the same adjectives its author used to refer to The Sacred Routes of Uyghur History, for it, too, is deeply empathetic and humane. And while it does not engage with Chinese history, I look forward to teaching it someday beside Timothy Brook’s Vermeer’s Hat or Jonathan Spence’s The Question of Hu, memorable books by China specialists that take us back in time and move between Europe and another part of the world in a similarly engaging and creative fashion.