“In Taiwan, Teens Protest Statues Honoring Former Ruler Chiang Kai-shek,”

Los Angeles Times headline, August 11, 2014

Like other historians of modern China, I give a fair number of class lectures that deal with Chiang Kai-shek (1887-1975), aka “The Generalissimo,” who was the most powerful man on the Chinese mainland from the late 1920s until 1949 and held that position in Taiwan from that point until his death. Not many of us, though, really warm to him. I know I never have. He comes across in most accounts as stiff and autocratic, and even sympathetic biographers seem impatient to switch from talking about him to telling stories about his glamorous Wellesley-educated wife, Soong Mei-ling. I’ve always been left cold by his speeches and writings, feeling they awkwardly tried to fuse two things that don’t really go together: adulation of Sun Yat-sen and his revolutionary vision, on the one hand, and veneration of traditional values and orderliness a la Confucius, on the other. And yet, seeing that Los Angeles Times headline last month, I almost felt sorry for the Generalissimo.

Even at its height, his personality cult on Taiwan was no match in grandeur for the one on the mainland established by his archrival Mao Zedong, whose Communist Party drove Chiang’s Nationalist Party into exile in 1949. And efforts now by students to get his statues removed from their campuses follow an earlier move in 2007 to rid other public settings of reminders of his rule—moves that Tong Lam discussed and showed images related to in an earlier post for this blog.

Surely, I mused, all this must be hard for Chiang’s ghost to bear. Especially knowing that, despite all the horrible things that Mao did while he was alive, the Chairman’s words are still quoted with approval by mainland leaders. And pilgrims still head to Beijing to gaze on Mao’s body lying in its crystal sarcophagus.

Yes, when I saw that headline, I almost felt sorry for Chiang—but not quite. Two things held me back.

First, while Mao was responsible for many more deaths than Chiang, the Generalissimo and the Chairman both did truly horrible things. In 1938, as part of a desperate and ultimately futile effort to halt Japanese invaders in their tracks, for example, Chiang ordered Nationalist soldiers to blow up a Yellow River dam, causing a flood that killed hundreds of thousands of civilians.* He then blamed the atrocity on the Japanese. And Chiang has blood on his hands for actions in Taiwan as well, including responsibility for a Nationalist massacre of civilians in 1947 (a counterpart in some ways to the better known Communist one in Beijing in 1989)—the marking of the sixtieth anniversary of which was what led in 2007 to that earlier move to do away with remnants of the Generalissimo’s personality cult.

The other reason I can’t quite feel sorry for Chiang is that Mao’s successors often seem happy to draw from his playbook, as Rana Mitter notes in Modern China: A Very Short Introduction. In that 2007 book, Mitter imagines Chiang’s ghost “wandering around China today” accompanied by Mao’s spirit. Looking down on a country whose officials celebrate Confucius, someone Chiang extolled and Mao vilified, and have stopped promoting Marxist notions of class struggle, which Mao stressed and Chiang had no time for, Mitter pictures the Generalissimo’s ghost “nodding in approval” and the Chairman’s “moaning at the destruction of his vision.”

And there’s been plenty more Confucius-related news from the mainland since 2007 that might similarly help make up for the anti-Chiang reports coming out of Taiwan. Chiang’s ghost, but not Mao’s, would have been happy in 2008 to see Confucius honored during the Opening Ceremonies of the 2008 Beijing Games, and to learn that “Confucius Peace Prize” had been created to compete with the Nobel one. (I’m not sure what either would have felt all that good about the first winner being Vladimir Putin!). I can also imagine Chiang’s spirit beaming and Mao’s spirit scowling each time that news comes of he Communist Party extending still further the global reach of its Confucius Institutes initiative.

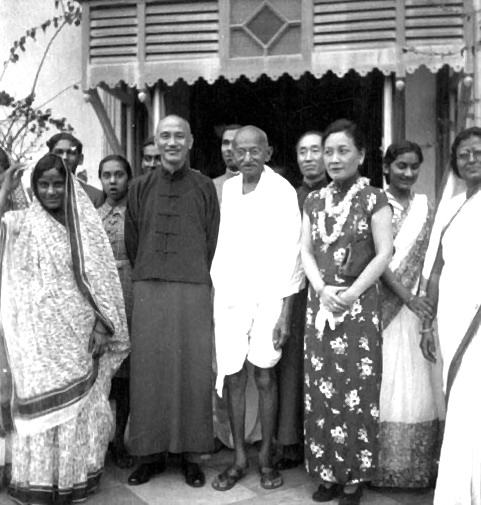

There are very different kinds of new stories coming out of China that might make the Generalissimo’s ghost feel that Xi Jinping, despite his fondness for quoting Mao, is interested in following in Chiang’s footsteps in some regards. For example, last week, when Xi made a high profile visit to India last week, his glamorous wife Peng Liyuan accompanied him. Peng is sometimes referred to as China’s “First First Lady,” but her trips abroad with her husband bring to mind ones that Chiang and Song took during World War II—including the 1942 one to India during which the photograph at the top of this post was taken.

What might make Chiang’s ghost happiest of all, though, is a totally different sort of mainland story, having to do with Xi. I am thinking of reports that describe him as being worried, as his predecessor Hu Jintao was, about the notion taking hold that China is now run by a small set of corrupt, tightly interconnected individuals with official ties who have grown far too rich and far too powerful.

Why would these stories of Xi’s anxiety make Chiang happy? Because the things being said about Xi and company now are so much like those that were said about Chiang and those close to him in the late 1940s, just before the forces of the Chairman defeated those of the Generalissimo in the battle for control of the mainland.

Chiang was not known for his sense of humor. Still, I can imagine his ghost, when reading about Xi and company lashing out at foreign journalists for detailing how much money relatives of top Chinese leaders have amassed, letting out a rare chuckle and saying: “What goes around comes around.”

* The Yellow River flood has recently gotten renewed attention from scholars: it is treated well in a recent Journal of Asian Studies article by Kathryn Edgerton-Tarpley, “From ‘Nourish the People’ to ‘Sacrifice for the Nation’: Changing Responses to Disaster in Late Imperial China” (May 2014 issue), for example, and in a fascinating book by Micah Muscilino, The Ecology of War: Henan Province, the Yellow River, and Beyond, 1938-1950, which is coming out in November.