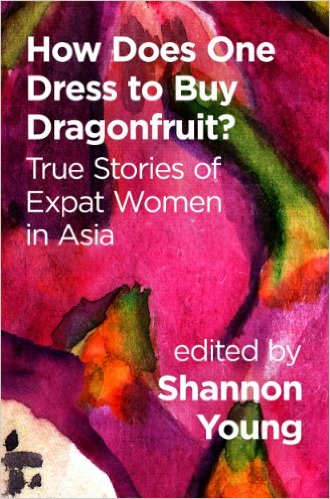

In my last China Blog post, I interviewed Hong Kong-based author Shannon Young, who talked about both her recently published memoir and a 2014 collection of essays she edited, titled How Does One Dress to Buy Dragonfruit? True Stories of Expat Women in Asia. That volume, Young explained, “gives a voice to the expat women who are often labeled as trailing spouses and dismissed,” their lives stereotyped as a parade of coffee dates, shopping expeditions, and yoga classes with other expatriate wives while their husbands work in government or business and their children attend international schools.

There are indeed plenty of women who move their families overseas at the behest of their husbands’ employers, though their lives are unquestionably more complex than the shallow vision I’ve just described. And there are also plenty of women who move abroad for other reasons: to learn a new language, to pursue their careers, to experience life in another country, or to leave behind an unsatisfying routine at home. Whether they live overseas with families, with partners, or alone, all expat women face a similar question, as Young writes in the foreword to Dragonfruit: “Who am I in this culture, this place?”

Some of the 26 women whose stories are included in Dragonfruit describe how they find freedom in their new homes. Sometimes this freedom is literal: Neha Mehta writes of feeling a greater sense of personal safety in Bangkok than she ever did in her native India, and of how this enables her to take public transportation and move about without her husband. For other women, freedom is figurative, as experiences abroad help them let go of lives that aren’t working for them anymore. In “Giving in to Mongolia,” Michelle Borok describes how at age 34, she took a vacation from her demanding job in Los Angeles to ride horses in Mongolia, where “I just got to be in charge of me, and I rediscovered how happy I could be with only myself for company.” No longer satisfied with her life in the United States, Borok moved to Mongolia and married a local man.

Many of the anthology’s contributors speak of being changed for the better by their time abroad, but Dragonfruit also includes essays on the difficulties involved in living overseas. Authors write of their struggles to communicate in foreign languages; to feel comfortable in settings where they don’t physically fit in; to navigate romantic relationships with partners who come from other cultures. And while moving to another country can feel like leaving behind “real life” at home, real-life problems — cancer, infertility, marriage troubles — don’t respect national boundaries.

One of the trickiest aspects of putting together an edited collection is achieving balance in the voices represented. Young writes in the foreword that she received 86 submissions for Dragonfruit and selected 26; of those, 13 essays are by women who live or have lived in Greater China (Hong Kong, Taiwan, or the PRC). Many of these essays — especially the ones by Dorcas Cheng-Tozun, Kaitlin Solimine, Christine Tan, Jocelyn Eikenburg, and Susan Blumberg-Kason — are the ones I liked the most in Dragonfruit, though I’ll admit that I’m surely biased toward China stories, and also that I was previously familiar with most of those authors (and in a couple of cases, have met them in person). But while I enjoyed the China essays, I wish a greater range of countries were represented in the collection. Just as “there are as many kinds of stories as there are expat women” (in Young’s words), the size and diversity of Asia means that expat women living in its different countries will have very different stories to tell. Dragonfruit offers a taste, but I’d welcome a second volume that features a broader assortment of women wrestling with the eternal expat question: “Who am I in this culture, this place?”