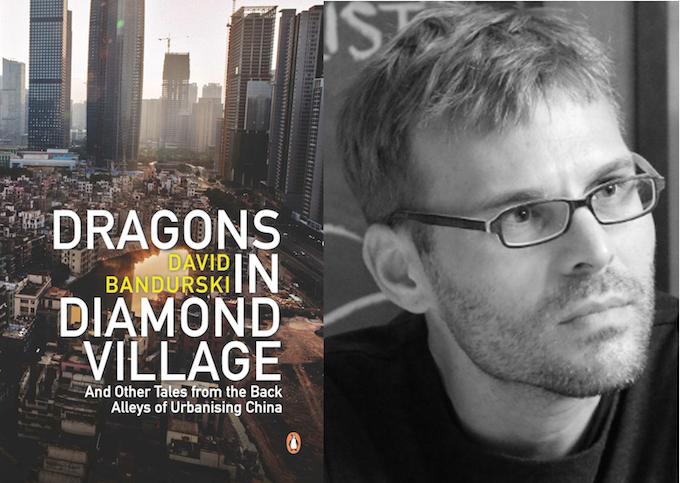

In last week’s post, three regular contributors to the China Blog gave suggestions for books dealing with Chinese themes that would make good holiday gifts. Next week’s post will take the form of a sequel, offering recommendations for last minute present shopping. So, it seems fitting that this post, which falls between, is an interview with the author of a very appealing book on China that would also be good to give to someone on your to-buy-for list. Published in other markets by Penguin last year but only recently available in the U.S., it is titled Dragons in Diamond Village: And Other Tales from the Back Alleys of Urbanising China, and it is by the versatile David Bandurski, an independent journalist, documentary filmmaker, and now book author as well. Bandurski joins me here to discuss recent developments in rural-urban unrest and the state of the Chinese media.

JEFFREY WASSERSTROM: I just saw this great Lucy Hornby review of your book in the Financial Times. Congratulations on that. Since the FT is paywalled (though probably accessible via a Google search), can you tell readers some things you particularly liked in it and explain why?

DAVID BANDURSKI: Well, all of the stories in my book take place in urban villages — rural villages, often with deep histories, caught up in the fabric of urban development. In our news coverage of China we don’t hear much about urban villages, but in fact they are ubiquitous. The FT review appreciates this. Hornby writes: “One Chinese researcher who specializes in analyzing local unrest on Beijing’s behalf has told the Financial Times he has a secret formula for starting his investigations: look for the unfinished construction site and ask the neighbors why it has been held up. The answer will almost always unlock an explanation for local grievances, as it does in Xian Village.”

That is so true. In fact, my habit when I was researching the book was to spread out a city map and circle the names of villages within the city limits, visiting as many as I could. Almost without fail I would find troubled semi-rural enclaves, tucked behind modern developments, facing exactly the kinds of problems I write about in the book. I also enjoyed the quote from Chinese novelist Yan Lianke, whose latest book, The Explosion Chronicles (just out in English translated by Carlos Rojas) is about urbanization. Talking about “an internal truth that’s been paved over,” he says: “You need to see how many people have been torn apart to create today’s cities.” That really resonates with me, as it no doubt would with the urban villagers I write about.

Having reviewed for newspapers myself, including the FT, I know how hard it can be to cover a complex book, as yours is, in a very short format. So, is there any aspect of the book that the reviewer didn’t get a chance to discuss that you’d like to mention?

The review focuses on the central narrative of the book, which is the story of Xian Village, a community right in the center of modern Guangzhou that has earned the nickname “Diamond Village” because of the value of its land. But I also try to weave this story together with other stories of what the review aptly calls “rural resistance in urban China.” So, for example, I also explore the story of a villager from the remote outskirts of the city whose native village is consumed by urbanization because local leaders want to cash in on land deals. They say, look, you have to move on, you can’t rely on the land anymore. His land is taken while he doing jail time for trying to lead opposition to a development planned in secret without community input. This act of theft sets him on a permanent path of resistance until he’s an unrepentant rights defender. He connects with other villagers and activists around the city, including, quite serendipitously, others I write about.

As I hope my book makes clear, this process has brought villagers and activists together in interesting ways, as part of a very harassed and fragmented rights movement.

Wukan was back in the news earlier this fall. Can you very briefly bring readers of this blog up to date on that story — and say a bit about how it relates to themes in Dragons in Diamond Village?

Sure. Wukan is a village in Guangdong Province, on the outskirts of the city of Lufeng, that broke into protests in 2011, with villagers calling for real democratic elections. They wanted action on corrupt land deals in which the government sold their land to developers without proper compensation — a frightfully common story, I’m afraid. To make the long story short, the villagers won the right to elect a new village leadership.

Protests broke out again in Wukan a couple of months ago after the democratically elected leader of the village, Lin Zulian, was jailed for corruption. He made a public confession on Chinese state television. When the villagers staged more protests in response to what all signs point to as a spurious prosecution and a forced public confession, riot police moved in, arresting villagers. Anxious to avoid a repeat of events in 2011, the authorities were also far more aggressive in dealing with foreign journalists trying to cover the story. I think this was retribution, four years delayed, against the village of Wukan for an experiment many Communist Party leaders surely saw as a dangerous precedent.

This experiment was, in my view, doomed from the start. How could the elected leaders possibly hope to resolve these land issues when leaders at every level over their heads had been complicit, and not only hoped their experiment would fail but had a clear interest in seeing land deals of this kind continue? The Financial Times reported in 2011 that 40 percent of local government revenue in this part of Guangdong came from land financing, basically the sale of cheap village land to property developers. In many cities, the percentage is even higher, and the incentive to take village land for profit is a huge driver of the kinds of cases of abuse and resistance I document.

How does all this fit in with Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption drive?

In spite of all of Xi’s talk about the need to strike tigers, or senior officials, as well as flies, I sense that local officials are more empowered than ever to take their own course. I worry that at the local level there is even less oversight than before. We saw this in the recent Wukan crackdown, when all of the information coming out was from the local government and police — something I also wrote about. So I think we could see more, not less, abuse of this kind under Xi.

As I suggested earlier, cases of abuse in urban villages are actually far more common than coverage, particularly in English, would lead you to believe. The execution of villager Jia Jinglong was recently in the international headlines about China. Jia’s crime was to murder the man responsible for the forced demolition of his home. That demolition was part of an urban village regeneration project started back in 2009, and very similar to the one underway in “Diamond Village.” Another recent headline in the New York Times read: “A Chinese Farmer’s Execution Shows the Pitfalls of Rapid Urbanization.” But it’s about more than just urbanization. It’s about lack of real rule of law, and lack of mechanisms of consultation like those hoped for in Wukan.

Can you fill in readers a bit more on Jia and what you think he stands for in the minds of many Chinese familiar with his case?

Jia Jinglong became a symbol of injustice for many Chinese, and his execution provoked fierce debate over unfairnesses in the system, and the impossibility of seeking recourse through legal channels. This is something I think you can see clearly in my book, the way villagers find it virtually impossible to be heard. Again, we see stories like this happening all the time. Back in May, a man named Fan Huapei was gunned down by police in Zhengzhou, the capital of Henan province. When I saw that the case stemmed from a forced property demolition, I did a quick search and found that, yes, the village in question was another urban village facing regeneration. It was home to about 500 local village families and more than 50,000 migrant workers. A chatroom post by a local resident pre-dating the tragedy said district leaders “regard laws as so much dung, and the ordinary peoples’ lives and property as so much livestock.” Fan had stabbed three men to death in a conflict over the forced demolition of his tenement property, a source of rental income from migrants. His case was eerily like that of Guangzhou villager Li Qizhong, whose story I tell in my book. I remember Li telling me on one of my visits to his “nail house” — the term in Chinese for a property holding out against demolition — that violence was the only language government leaders understood, and so he would speak to them in their language.

Last but by no means least, the last year has been an incredibly eventful and often worrisome period for two issues that you track very closely: control of media on the mainland and freedom of speech in Hong Kong. Two places I go to in order to keep up with developments relating to these topics are the China Media Project and the Hong Kong Free Press. What other sources would you recommend as worth checking out? Is there someone who is consistently doing good work on them that readers of this blog might want to follow?

Media and publishing in Hong Kong are certainly under greater and greater pressure. The case of the missing booksellers has gotten a lot of international attention this year, highlighting interference by Chinese authorities but problems have been going on a lot longer than that. The great thing about Hong Kong is that this is a place where we can still stand up and push back. This is why a number of us recently got together to relaunch the Hong Kong chapter of PEN, the international writers’ group. We want to promote and defend freedom of expression in Hong Kong, and to promote literary creation of all kinds, in both Chinese and English. So I encourage anyone interested to follow us or become involved. We have plenty of interesting events in store.

Hong Kong is also seeing a burst of start-up activity in the media. You mentioned Hong Kong Free Press, which publishes in English, and they are a great source. One of my favorite Chinese-language outlets is Initium, launched last year by veteran journalist Zhang Jieping. I think they manage quite well to cover affairs in Hong Kong, China and Taiwan in ways that others don’t. Some of their reporters are escapees, in fact, from mainland media.

In retrospect, I think we could say that ten years ago we were spoilt for choice if we wanted rational, intelligent commentaries, or even in-depth reporting, from mainland Chinese media. A lot of those voices have disappeared, or at least gone underground for the time being to private WeChat forums, or old-fashioned e-mail networks. Just this year, for example, we saw the demise of Consensus Net, which had been a leading platform for writing from Chinese intellectuals. I still turn almost daily to Caixin Media, which has maintained its professional standards, even if there is less it can cover.

Increasingly, I find I am turning to more classic readings of Communist Party discourse. And that means, unfortunately, daily digs into the official People’s Daily to read the tea leaves as best I can. Chinese President Xi Jinping has recently pushed himself as “the core,” which suggests he is positioning himself for the next major Party meeting a year from now. What happens in the next year will tell us a lot about what direction China and China’s media are heading. I am anxiously watching those signs, and readers are of course welcome to follow my writings at the China Media Project.