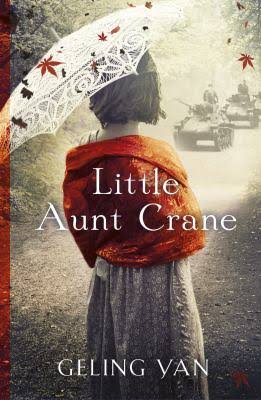

Yan Geling is a Chinese novelist, born in Shanghai, who lives in Berlin and travels frequently to China. Her novel The Flowers of War was made into a film starring Christian Bale, and she has won wide acclaim both inside and outside of China. Her new novel in English, Little Aunt Crane (translated by Esther Tyldesley) is a wonderfully empathic story of a young Japanese girl, Tatsuru, who stays behind in China after the end of World War Two. Tatsura becomes the second wife of a Chinese heir, and befriends the first wife Xiaohuan during the decades of political tumult that follow. It’s an enjoyable read and a fresh narrative perspective on Chinese history. I asked Yan Geling some questions on email about her process, intentions, and themes.

ALEC ASH: How did you first begin to learn about Japanese colonists left behind in China after the end of World War Two, and why did you want to write about it as a subject for your novel Little Aunt Crane?

YAN GELING: Years ago, one of my childhood friends told me a story about twin brothers in her class who intrigued her. Her classmates discussed them behind their backs, saying that there was a woman in their house besides their mother who seemed to have a mysterious position in their family. This woman would kneel down to tie the boys’ father’s shoelaces and make everybody take off their shoes before entering the house. Later my friend and her classmates discovered that this mysterious woman was not a Chinese but a Japanese who was sold to this family in a sack during the Japanese retreat from China, and she was the twins’ natural mother. I was amazed by the story and couldn’t help imagining how all of them had lived in secrecy and harmony in a Chinese neighborhood. After I moved to the U.S., I told the story to many friends in artistic and literary circles, and they all thought it was good material for a novel. One of my author friends even bought me a kimono to encourage me to write it, but not until 2007 did I muster enough courage to create a novel whose main female character was Japanese. What also made it possible to carry out expensive research in Japan was that my husband was reinstated in the U.S. Foreign Service as a diplomat, and we moved to Taiwan in 2006. By then our financial situation allowed me to hire interpreters to help me do research in a village in central Japan that had been divided in two, with one half of its farmers going to Northeast China as colonists in the early 1930s.

History is hugely important in understanding contemporary China, especially its fraught relations with Japan. What can Tatsuru and Xiaohuan’s friendship teach us about China today?

I don’t know. I don’t think a novel has a function or a mission such as teaching somebody something. Instead, I think a novelist, by writing a story in the most vivid way, with poetry of language and by sharing it with the public, is willing to discover the truth about the story together with the readers. I have written stories about women suffering during wars and after wars, because I think that no matter who wins or loses, women on both side are the ultimate victims. Their bodies are the last part of a defeated country to be conquered, to be violated. They are the mothers, wives, and daughters of soldiers whose lost lives leave voids in the women’s lives, too deep to be filled. In this sense, Xiaohuan and Crane (Tatsuru) have a shared understanding and sympathy with each other beyond their own knowledge.

In both this novel and in The Flowers of War, finding humanity in the midst of chaos is a recurring theme. So much of China’s recent past has been a litany of horrors, yet you focus on small acts of kindness and bravery. Does this mean you’re an optimist?

I think the Chinese are a people of survival. We are all wonderful survivors. We have risen in population during the last century, a century in which wars and famines have happened all the time. We have survived natural and political disasters almost every other year during the last sixty years. Without optimism I don’t think my people could live until today. I have gone to poor rural areas in China and seen destitute people joke and jest and laugh. I can imagine Chinese at the bottom of society, surviving like them over thousands of years. They must have a good sense of humor to go through hardship, and they must have learned how to steal whatever small pleasure they can to hold on to their dear life. I can’t imagine that any people could survive so many centuries of sorrow if to live only means to suffer. They have learned to steal joy, however little, out of the overall suffering.

You served with the People’s Liberation Army during the Cultural Revolution as a dancer in an entertainment troupe from the age of 12. What were some of your other experiences in the PLA, and how did they influence your writing later?

I think my becoming a writer has much to do with my tough upbringing, including my experience in the army. When the Cultural Revolution took place, I was seven, and it was human nature playing itself out before my eyes. Unfortunately, I was too young for that. And because my father, a writer and a freethinker, had an unpopular political status, I was ostracized and felt very marginal in the army performing troop. It bothered me at the time, but I discovered later that I benefited from it when I started to write. I believe all artists and writers should be independent from the mainstream, so they won’t take the values system or moral standards of the mainstream for granted. On the contrary, they should make it their duty to question and doubt the way of life and way of thinking of the mainstream. Now I am glad to live overseas as a Chinese writer, to remain independent and critical of both sides.

Who are some of your favorite Chinese authors, both in the past and today, and why?

I never use the word favorite when it comes to literature, because I like too many authors whose styles are very different from one another. I like Cao Xueqin, author of Dream of the Red Chamber. I also like my contemporaries, such as Mo Yan, Wang Anyi, Yu Hua, and Jin Yucheng.

For another sample of Yan Geling’s writing, read Disappointing Returns, an extract from her latest novel in Chinese, translated by Dave Haysom on Read Paper Republic