Photo: Mary Guo in Beijing, April 15, 2014.

By Lu-Hai Liang

Let’s start with Mary. Well that’s her English name anyway. We met seven years ago in Yangshuo, a pretty little town in southern China where she was studying English. I liked her sparky personality and sense of fun, and we became friends. I was teaching English, taking a year out before I started university. I was 18, Mary 21.

Skip forward seven years to the present, and I’m back in China, this time to work in Beijing. I am British, of Chinese heritage. Mary is Chinese and her heritage is that of rural dwellers, known in Chinese as “nongmin” or farmers.

I’ve never known Mary to have a boyfriend but she recently told me, after I asked about her relationship status for this article, that she has had two, including the one she is currently seeing. I was surprised to hear this, since Mary had not mentioned any of this in our previous meetings (she works in Beijing). She is 28 now, which, according to the general consensus within Chinese society, makes her more-than-ready for marriage.

Except, she doesn’t feel ready. In China there is now a common though derogatory term for those over the age of 27, female and unmarried. Coined in 2007, it is “Shengnü,” meaning “leftover woman” (as in spoiled food, leftovers). The term’s implications are obvious — that older, unmarried women are to be pitied for being left out of marriage. Very recently when talking with Mary I had sensed a sadness in her. I thought perhaps she had been dwelling on these pressures.

A book authored by Leta Hong Fincher explores the “Shengnü” phenomenon and gender equality in China in depth. I was curious to find out what one of my oldest Chinese female friends thought, whether it had affected her. So over drinks (mango shake and milk tea) we discussed the issue. Here is some of what she said:

“I was 24-25 when my parents started to ask about boyfriends.”

“I think there are more ‘shengnan’ [leftover men] than leftover women.”

“Post-80s women look after, think about themselves. We think more about protecting our own rights, we think more carefully. We have open eyes to see a lot of social things; from websites, friends. The government may not like it, but we have to protect ourselves.”

Other things worth knowing about Mary: She has the highest education level of her family. She feels she is independent and says that her parents “firmly support every decision I make.” Her elder sister married when she was 22. She admits to envying her sister a little for her settled life, but also says her sister envies her for her freedom. Overall, she is happy that she did not marry young, stressing: “I know myself — I know what kind of life I want.”

There is a growing body of literature, written mostly by journalists, that seeks to explain the “Shengnü” issue. Not surprisingly, there is much criticism of the term and many writers have noted the deranged irony of the official Chinese women’s association, which ostensibly promotes male-female equality, playing an important role in popularizing it. I had expected to find my female friends, if still single, to be sad and anxious about their unmarried fates. But, in Mary at least, I found instead fortitude and strength.

But the term “Shengnü” presents many prejudicial problems. It has been deployed to put down women who are educated, urban and career-minded. It has been used to exert pressure so that these “top-level women” will marry younger, and so the men of China, of which there is a surplus, will be able to produce children. It is used with an eye to heading off social unrest and societal problems that might arise from too many men being single. What better way to relieve that than to flip the pressure onto women by stigmatizing those just unwilling to hurry up and marry?

It has not always been this way.

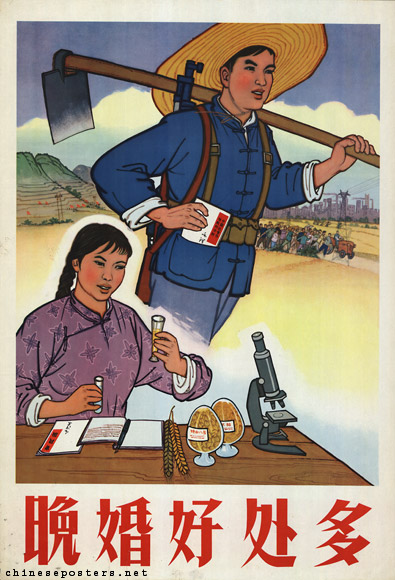

My mother was 24 when she married my father. The date was April 26, 1987, in Guilin, a famously beautiful city in southern China known for its karst and riverine landscape. My father was 31. My mother says at that time you could get a “wedding holiday” if you married after the age of 24. “The government encourage [sic] people to marry late, friends and family gave no pressure to me. Actually they all felt I marry too quickly,” she tells me via email, from England, the country to which she and my father emigrated (they later divorced).

She felt somewhat pushed into marriage by my father. Her mother (my grandmother) married when she was around 15 or 16 — she gave birth to her first child when she was 17. My grandmother would go to her aunt’s home when she was a teenager as she treated her well. My grandfather’s mother would often go there too, so my grandmother’s aunt acted as matchmaker.

In that generation, a matchmaker (meiren) was typically needed to arrange relationships. My grandmother was transported from her home to the home of my grandfather when she was 15 years old, having never seen my grandfather’s face before.

It seems in China that the change from generation to generation can be massive and swift, as if in one decade or two a button is pushed and the expectations of an entire people are switched. The terms people are influenced by, even if it’s as risible and odious an invention as “Shengnü,” can be effective. But those subject to them are not always so easily swayed.

Michelle Wang is 27 and works in the aviation industry in Beijing. She makes decent money and has a Masters degree from the University of Sydney. Born in Xi’an, she speaks fluent English and considers her family, when pushed to define them, to be upper-middle class. She identifies as ambitious and career-minded. Her parents are divorced.

“‘Shengnü’ have more advantage than men,” she tells me. “Because they can make children, and that’s why most [men] want to get married.” She is aware of the economic dimensions of marriage that exist in China, in which real estate often belongs only to the husband. If she marries she says she would insist that, if they were to buy a house, both her name and her husband’s would be on the deed.

Since the end of 2013, she has felt intense pressure coming from her parents who keep asking her about men. But she’s skeptical about marriage as a concept, explaining that her parent’s divorce contributes a lot to that. She would like to find a partner (she speaks of this figure as “The One”), but not necessarily a husband.

“I used to firmly believe marriage should be for those in love,” says Wang. “Now I know better. I’ve heard that ‘people can’t be happy without marriage’ — in time I might believe them, but not at the moment.”

“Financial independence,” she continues, “is the key for girls. Women now have the choice to be ‘Shengnü’. Women used to not have the independence to choose not to get married. It is unfortunate to be seen as ‘Shengnü, ‘ but actually it’s a sign of development, of evolution, of social progress, because in the old days, they didn’t have the option to be ‘sheng’ — ‘leftover’.”

She sums up her feelings with a succinct defiance: “The phenomenon is a sign of progress, not the term itself.”

Lu-Hai Liang is a freelance journalist based in Beijing whose work has appeared in publications such as the Guardian and the New Statesman. For his blogs posts and other information about him, see his website: http://theluhai.com/.