thesBy Jeffrey Wasserstrom

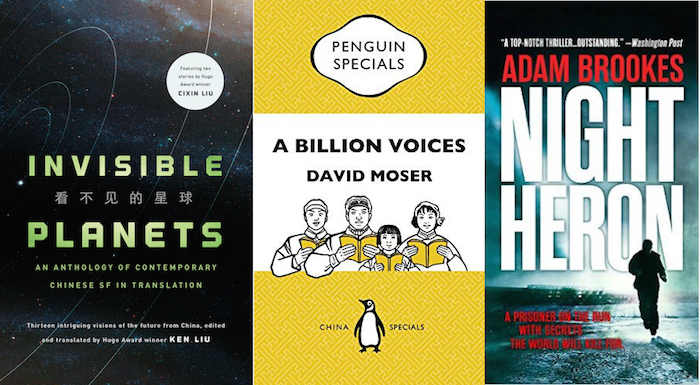

In this follow up to our December 7 post, two China Blog regulars, Alec Ash and Maura Elizabeth Cunningham, recommend a quartet of titles. These titles, which deal with everything from down-and-out residents of contemporary Beijing to a pair of American journalists who fell in love while covering World War II in Asia, would make excellent last minute presents for others — or enjoyable items to buy for yourself with any gift cards you get. I didn’t get a chance to do a full write-up for my own selections, but will slip a plug for them into this intro without extended explanation. I’ll just note that former BBC reporter Adam Brookes is two-thirds of the way through what will eventually be a trilogy of novels of intrigue that move between China and other parts of the world, and both Night Heron and Spy Games, each now available in paperback, are unusually well crafted page-turners. (For more about each book, see these LARB reviews of them, here and here.)

As an English literature major gone rogue in China, I’m a believer in understanding this country through its literary output. There are social offshoots to the country’s growth that can be best expressed ambiguously, or through a veil – and other truths that can only be voiced obliquely for fear of censorship. With that in mind, I’m recommending two works of Chinese fiction with a certain invisible something in common.

The first is The Invisibility Cloak by Ge Fei, a well-respected novelist in China now garnering some deserved international attention in translation. The novella brings contemporary Beijing to life through the biting and occasionally bizarre story of one of its down-and-outs. Translated by Canaan Morse, a poet and editor with deep knowledge of Chinese literature, it’s an inventive and enjoyable contemplation on China’s urban noise.

The second is Invisible Planets, an anthology of Chinese science fiction translated and compiled by Ken Liu, himself a talented author. I’ve long been impressed by Chinese sci fi as a creative means to discuss Chinese reality, and this collection pulls together some of my favorite writers, from Hao Jingfang to Chen Qiufan, as well as Liu Cixin. You won’t regret dipping into this one for a truly imaginative take on modern China.

This month marks the 75th anniversary of Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor, a story that’s familiar to anyone who has taken a basic American history course or sat through the regrettable Ben Affleck movie. Not so many people know much about what was happening on the other side of the Pacific in December 1941, though, and I’d recommend expanding their knowledge with Bill Lascher’s Eve of a Hundred Midnights: The Star-Crossed Love Story of Two WWII Correspondents and Their Escape Across the Pacific, which I borrowed from the library soon after reading the interview Paul French did with him here at the China Blog. Lascher follows the lives and careers of American journalists Mel and Annalee Jacoby as they reported from China before the United States entered the war and the Philippines immediately after. Big-name figures like Helen Keller, Henry Luce, and Song Meiling played roles in the Jacobys’ lives (as did two famous pandas that I’ve written about) but never overshadow the pair at the center of Lascher’s compelling narrative. Appropriately enough for a couple that first teamed up to write a film script, Mel and Annalee’s dramatic story would make for a fine movie—surely better than Pearl Harbor.

Back when I started studying Chinese in college, my first language professor distributed photocopies of a 1991 essay called “Why Chinese Is So Damn Hard,” written by a scholar named David Moser. In that piece—which I’ve read multiple times in the decade-plus since first encountering it—Moser displayed his knack for explaining the technicalities of the Chinese language in a manner that’s both accessible and humorous (he also reassured me that yes, Chinese really was as hard as I thought). Now, I think first-year Chinese students should be required to read Moser’s recent book, A Billion Voices: China’s Search for a Common Language, a short volume out of Penguin’s “China Specials” line that would make a perfect stocking stuffer. In fewer than a hundred pages, Moser recounts the various twentieth-century efforts to create a standard version of Chinese that eventually resulted in what we now call Putonghua, or the “common language.” As Moser explains, the Chinese we speak today is a political creation—and even with attempts to simplify and democratize the language, and the advent of digitization, it remains so. damn. hard.