“To me the choice was easy…I thought it was better to have 90 percent of the book available here than zero.”

Ezra Vogel, author of Deng Xiaoping and the Transformation of Modern China, statement made during a Chinese book tour.

“As an academic who doesn’t write for a large publication, I’m always happy to have a readership that extends beyond the three people in my family.”

Rebecca Karl, author of Mao Zedong and China in the Twentieth-Century World.

“I kept waiting for the other shoe to fall.”

Michael Meyer, author of The Last Days of Old Beijing.

[All quotes appeared in Andrew Jacobs, “Authors Accept Censors’ Rules to Sell in China,” New York Times, October 19, 2013.]

Here are some questions that students, friends, and people who introduce themselves to me after I’ve given a public talk on China often ask:

Are you sorry that none of the books you’ve written have come out in Chinese editions?

How much would you be willing to let Chinese publishers cut from your books, if told that allowing some things to get intentionally lost in translation was what it would take for these works to be sold on the mainland?

Would you balk at cutting a few sentences, be fine with deleting a whole chapter, or perhaps even be okay with trimming segments here and there throughout a book?

How strongly would you push back if asked for other sorts of changes, like allowing your book to have a dramatically different title in the Chinese edition?

I’ll likely get asked things like this more often now, thanks to Andrew Jacobs, whose recent article on the publication of Western works in mainland China has generated a lot of buzz. It’s no surprise that the article has caught the interest of China specialists. Many of us are fascinated by the challenge of sorting out what has and hasn’t changed about Chinese publishing and censorship in recent years. Jacobs draws attention to both novelties of the present (not long ago, books dealing even in part with sensitive issues simply would not be translated) as well as things that are holdovers from past times, such as the paranoia about protecting Party officials’ images that led to a reference to Deng dropping a dumpling being cut from Vogel’s book, and a text about a mayor and a mistress ending up one of the very few things excised from Meyer’s. And Jacobs focuses on three different sorts of members of our tribe: sociologist Vogel (whose Deng biography is selling briskly in China), historian Karl (whose book will likely be published soon by Hunan People’s Press), and journalist Meyer (whose book was retitled Zaihui, Lao Beijing, or “See You Again, Old Beijing,” in an effort, Jacobs writes, to make an often dismayed look at destruction seem a “nostalgic love letter”).

What is more notable is how much interest in the article there has been beyond specialist circles. On October 23, for example, the Guardian ran a follow-up article, “Author Bows to Chinese Censorship of his Deng Biography,” which zeroed in on Vogel’s relatively easy acceptance of modifying his work so that it could appear in China. The next day, “The Banal Reality of Censoring Books in China” appeared on the History News Network website. This article began with HNN editor David Walsh describing the battle Karl fought — and won — to keep Hunan People’s Press from going forward with their initial plan to present her book to Chinese readers as a straightforward biography of Mao, with an altered title to match.

Reading these three articles on censorship has made me appreciate anew a basic fact about the questions regarding translation, accommodation, censorship and so forth I sometimes get asked: at least for me, these queries usually cannot be answered as simply as people would like. And the same will be true now if I’m asked whether, like Vogel, I’ll be happy if “90 percent” of one my books can make its way into the Chinese market. It all depends, I’ll say, on which book we are talking about.

In the case of China’s Brave New World — and Other Tales for Global Times, which is comprised of separate though thematically connected essays, I was ready at one point to try to get a version published on the mainland that was only about 70% as long as the original, with several chapters that would clearly have created problems left out. (A friend found a publishing house that initially seemed ready to go forward with the book in that form, but then higher ups within it had second thoughts and the plans to bring out the translation were scrapped.)

With my first book, Student Protests in Twentieth-Century China: The View from Shanghai, which is mostly about pre-1949 events but has an “Epilogue” (perhaps making up 7% of the text) stressing parallels between those struggles and upheavals of the 1980s, on the other hand, I would view cutting out 10% as far too much. I would rather it not be published than come out sans that “Epilogue” and also stripped of passing comments in other chapters about the clear links and parallels between the “good,” in Chinese Communist Party eyes, protests that helped it rise to power and the “bad” ones that challenged its legitimacy in 1989.

Or, rather, I’d only consider going forward with a version like that if the press in question agreed to a condition I can’t imagine it would: marking each cut with an ellipsis to show that something in the original was no longer there, and putting a warning on the cover, like those you see when R rated movies are shown on an airplane, noting that the work has been modified for presentation in this particular setting. Without something like that done, I would worry that the book could too easily be read as supporting notions that I don’t agree with. For example, such cuts would eliminate the parallels I draw between protests of the 1940s, which were concerned in part with drawing attention to the flaws of the authoritarian and corrupt Nationalist Party government of that era, and those that erupted four decades later, which were concerned in part with drawing attention to the flaws of the authoritarian and corrupt Communist Party government of that time.

It might seem that at least one question mentioned at the start of this post would lend itself to a straightforward answer — the one about whether I’m frustrated that none of my books has come out in a Chinese edition yet. Of course, since I share Karl’s desire to be read broadly, I’d love to have all my books available in as many translations as possible, and since I write about China, reaching Chinese readers is particularly desirable. Still, this question needs clarification and contextualization, even though neither of the books just mentioned has been translated into simplified characters by a Chinese publisher, and the same goes for the other two books I’ve written, Global Shanghai, 1850-2010 and China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know.

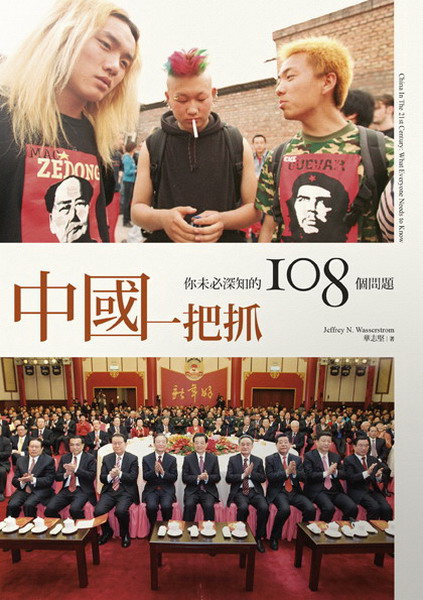

The most important thing to note is that there is a Chinese-language version out of China in the 21st Century, just not a simplified-character one. A complex-character translation of the book’s second edition, which I updated in collaboration with fellow LARB “China Blog” regular Maura Elizabeth Cunningham, was published this summer. It’s now readily available for sale in both Taiwan and Hong Kong, and some copies could already be making their way into the hands of readers in cities such as Shanghai and Beijing, even if this edition can’t be sold in mainland bookstores. So, it’s not quite true that there are no “Chinese editions” of my works. It’s not even accurate to say none of them can be sold openly in the People’s Republic of China, since Hong Kong is now a part of that country, albeit one where distinctive rules on publishing apply — something demonstrated by such things as there being a Hong Kong translation of Vogel’s biography of Deng that I’ve been told includes passages snipped out of the mainland edition.

Finally, what about sticking to your guns on titles? I admire Karl’s determination not to have her Mao book, which is very different in aims and scope than a standard biography, recast to seem like it was just that. I can also see, though, why Meyer might have felt differently about The Last Days of Old Beijing becoming Zaihui, Lao Beijing. If you are interested in making a living as an author in the present era, there’s a need to pick your battles, and he also might well have felt that going along with the title change provided him more leverage in working to keep parts of the book’s content he cared about from being cut. Added to this, there’s a basic difference between Karl and Meyer’s past experiences with publication, since the former’s articles have most often been published in scholarly venues, the latter’s in magazines and newspapers. If you write for general interest rather than academic venues, you simply get used to having titles other than the ones you came up with placed above your work. In my relatively amphibious career, I try to keep this in mind, so I can roll with the punches when my articles for non-scholarly periodicals are retitled (though ones that seem to me to veer too far from my original meaning certainly annoy me) yet ready to push back if anyone tries to get me to give up on a title I like for something I’ve written for an academic journal.

As for books, I was so happy to see one of my books finally come out in a Chinese-language edition of some kind, that it didn’t bother me that I wasn’t even consulted about what China in the 21st Century: What Everyone Needs to Know would be renamed. And just in case any Chinese publisher is reading this post, I’d like to make it clear that I’m open to having Global Shanghai, 1850-2010 retitled. It’s hardly a “nostalgic love letter” to the city that is its focus, but it does have a sense of old patterns returning in novel forms in the metropolis; so, especially if Meyer’s work sells as well as it should (it’s a really good book), I’d even be willing to consider Zaihui, Lao Shanghai. Hell, with a title like “See You Again, Old Shanghai,” someone might even bid for the movie rights.

* For more on the Chinese translations of The Last Days of Old Beijing — in the plural, since Taiwan and mainland editions have both come out — and the author’s experiences touring to promote these books in Asia, check out Michael Meyer’s “See You Again, Old Beijing,” an engaging and thoughtful memoir cum commentary published in SLATE. Also of interest are two “Letters to the Editor” inspired by Jacobs’s article that have appeared in the New York Times. One of these, from China specialist John Israel, recounts an interesting experience the author had with a sensitive issue of translation. The other is from the President of Ohio Wesleyan University, noting that Vogel “passed on all rights to income from mainland China sales” of his Deng biography to that school, his “alma mater.” The proceeds are to be used to establish “a permanent endowment to support Ohio Wesleyan students engaged in international study, with a preference for research and travel involving East Asia.”