By Austin Dean

Maps are at the center of every territorial dispute. My map says this parcel of land over here belongs to me and always has; your map says that same parcel of land has belonged to you since time immemorial. Armed with supposed cartographic confirmation of competing claims, border dispute can last for decades.

In the midst of a territorial dispute, it is important to put maps on display. During Chinese National Day festivities last October, a large exhibit titled “Diaoyu Islands: History and Sovereignty” dominated the first floor of the National Library in Beijing. The intent was to overwhelm. Featuring a number of old documents, manuscripts, and maps, the message was clear: these rocks in the middle of the sea belong to us and always have.

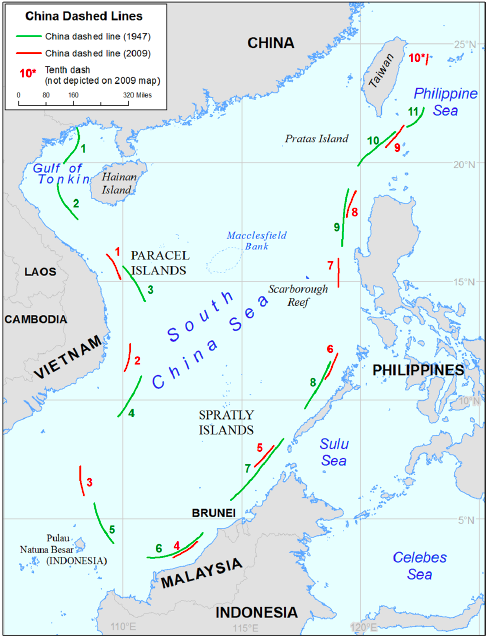

It was just the latest in a string of attempts to assert control over a disputed territory: in 1947 the Guomindang, still in power on the mainland, published the 11-dash line showing Chinese claims in the South China Sea. A 2009 map released by the PRC had nine dashes (with another one around Taiwan, just in case anyone forgot). The dashes in the 1947 and the 2009 maps don’t match up. According to a note prepared by the U.S. Department of State last December, “the sizes and locations of the dashes from the 2009 map are generally shorter and closer to the coasts of neighboring States than the dashes in the 1947 map.”

Of course, other countries have their own maps to assert their own territorial claims. Looking at a map of the tangled, overlapping claims in the South China Sea and thinking about all the things that could go wrong is more than enough to keep one up at night.

The world, as New Yorker writer Adam Gopnik reminds us, “is visible only through the maps that we make of it.” Because maps are so important, they “are made by minds attuned to the relations of power.” But sometimes maps are made by people whose minds are not attuned to relations of power and reflect human error more than power structures.

In the mid-1950s, the People’s Republic of China had a map problem—or, more accurately, several map problems. Stuffed in a file of materials from the Ministry of Education in the Beijing Municipal Archives is a report about a host of serious cartographical errors. In tune with the ideological atmosphere of the early Cold War, one type of map produced in the early PRC used color codes to define a country’s position: a socialist country, a newly democratic country, a country in transition, or a colonized/semi-colonized country. It was important for people to know not just where the country was physically, but where it was ideologically.

The errors began there. Some copies of the map labeled India, Indonesia, and Myanmar as colonized or half-colonized. Those were all wrong; all three countries became independent nations before 1950. That was not the only error. Maps also labeled areas of the world according to whether they were peaceful or fighting a war of liberation. India and most of the countries in the Middle East were mislabeled.

Beyond mistakes of ideological category, maps also mixed up borders. Sure to anger China’s ally in Pakistan, some maps showed that the disputed province of Kashmir actually belonged to India. The border between India and Bhutan was not clear, and the labels for Bhutan and Nepal actually appeared on the inside the border of China.

These mistakes, the Ministry of Education complained, not only made it difficult to educate students in the changing international situation but also caused problems for Chinese foreign policy goals. How could Chinese diplomats be effective when their maps contained all these basics errors? It made the newly established government under the Communist Party look like a not very serious operation. The Ministry of Education instructed schools, universities, and research institutes to inspect the maps hanging in their facilities for these and other mistakes and to take them down if discovered.

One broader point stands out about this small episode: the Chinese government, in the past and present, can at once appear both organized and disordered.

When looking from the outside and from a distance, the government of the PRC often appears efficient and adept at getting things done. This perceived efficiency is at the heart of the envy expressed by those like New York Times columnist Thomas Freidman, who pondered how much the United States could get done if “we could just be China for a day.” From the inside, though, the picture is usually different. What looks organized and efficient may actually be helter-skelter and halting. If we were China for just one day, there is a fair chance we would spend it attending a lot of hastily called meetings with no seeming point and sitting for hours guzzling tea as people gave boring speeches. Alternatively, we might spend it dealing with the fallout from whatever small crisis was flaring up at the moment.

In the case of the mistaken map, the committee in charge of mapmaking was organized enough to categorize the ideological geography of the early Cold War, but somewhere along the way India ended up still belonging to England and its borders got moved around. Made aware of the issue, the Ministry of Education called for a nation-wide inspection, with the result—if people actually listened to the communiqué—that cadres went around inspecting maps instead of doing whatever else they had going on that day.

In thinking about the PRC, it is important to hold this seeming contradiction in your mind: it is both organized and messy. Maps, though, don’t allow for such subtlety. My map has to say this land has always belonged to me and your map has to show the exact opposite.

(The missive on the mistaken map is in file 153-004-01782 in the Beijing Municipal Archives.)