When I am busy with a book project, the period between the end of the spring quarter and start of the fall can mean a welcome chance to make major headway. But it also means periodically searching out fiction to read that offers a complete break from the book’s subject matter. Usually, this has involved steering clear of all novels relating to a place: China. This summer, since I am working on a book about the Boxers and the international invading force mustered to fight that messianic anti-Christian group, it meant searching for novels that had nothing to do with a year: 1900.

One work of fiction that is presently providing me with the kind of diverting temporal break I desire is Shanghai Redemption, the latest novel in Qiu Xialong’s successful Inspector Chen series. I’m enjoying reading an advance copy of this book, partly because its action takes place in the recent past and present rather than more than a century ago. In addition, at least so far, it has been blissfully free of even passing allusions to the Boxers, who did some brutal things, and the international invasion, which also involved some horrendous acts of violence. It may seem silly to imagine that either the Boxers or the Baguo lianjun (Eight Countries Allied Army), as the 1900 invading force is known in Chinese, would make their way into a contribution to a series that has focused on Shanghai from the 1990s on. But you never know. Allusions to them show up in some very surprising places.

In a 1990 speech, “We Are Working to Revitalize the Chinese Nation,” for example, Deng Xiaoping brought up, seemingly out of nowhere, the Baguo lianjun. He said that, when he heard that seven foreign countries were planning to use economic measures to punish the CCP for the previous year’s June 4th Massacre, this immediately made him think of the time 90 years earlier when a slightly larger set of foreign powers, including some of the same ones, had invaded China.

When it comes to the Boxers, they are referenced in, among many other works of fiction, Neal Stephenson’s cyberpunk classic The Diamond Age. The action in that 1995 novel unfolds in a hypermodern Shanghai, just as Qiu’s new novel does, but had I chosen to read it rather than Shanghai Redemption to get away from the events of 1900 this summer, it would not have given me the same kind of complete break from the book I’m writing. The characters in The Diamond Age include neo-Victorians, who have eccentric habits like reading things written on paper rather than screens, long after this stopped being common, and also neo-Boxers. The latter are eager to succeed in driving foreigners out of China, something that their namesakes of an earlier time had failed to accomplish.

While Shanghai Redemption, which was just published earlier this week, is providing a welcome break from my current book project’s subject, its opening chapters set me thinking yet again about an author whose work obsessed me while writing an earlier one. Namely, Aldous Huxley whose best known novel, a futuristic foray into science fiction published in the early 1930s, inspired the title of my 2007 book, China’s Brave New World—And Other Tales for Global Times.

Qiu’s new novel opens with Inspector Chen, a literary minded policemen who writes poetry and translates T.S. Eliot, visiting the cemetery where his father is buried. He is amazed upon arrival at the evidence it provides that conspicuous consumption, ostentation, and crass forms of materialism have begun to affect even the realms of burial and mourning in today’s booming, status conscious China. There is much about the scene at the cemetery that speaks to its distinctively Chinese setting, such as elements of the dialog that refer to ideas of Confucian filial piety. Still, when Qiu describes this resting place for the dead as having been given new touches that “add to” its “pompous appearance” and thereby help it to conform to the dictates of a “materialist age,” I immediately thought of the early pages of Huxley’s After Many a Summer Dies the Swan. In that work, written at the end of the 1930s, a British visitor, presumably based on Huxley himself, visits a Southern California cemetery and is struck by the way that it encapsulates all that is strangest about nouveau riche American excess.

Here are some excerpts from Qiu’s novel:

Chen hadn’t been to the cemetery in several years, and it, like everywhere else in Suzhou, had changed. The sign at the entrance appeared to have been recently repainted, and a new arch stood over the entrance, redolent with the grandeur of a gate to an ancient palace. It added a majestic touch to the scene, standing against the verdant hills stretching to the horizon…. He walked down the hill to the office and pushed open the door. Inside he saw several small windows where people were paying their fees, and along the opposite wall, a row of chairs where customers sat waiting. Next to the row of chairs were two or three sofas marked with a sign reading VIP AREA. That section was probably for the people responsible for the luxurious new graves on the hillside.

Here, meanwhile, are some sample lines from Huxley’s:

The car turned a shoulder of orange rock, and there, all at once, on a summit hitherto concealed from view, was a huge sky sign, with the word BEVERLY PANTHEON, THE PERSONALITY CEMETERY, in six foot neon tubes and, above it, on the very crest, a full scale reproduction of the Leaning Tower of Pisa, only this one didn’t lean…

An hour later, they were on their way again, having seen everything. Everything. The sloping lawns, like a green oasis in the mountain desolation. The groups of trees. The tombstones in the grass…a miniature reproduction of Holy Trinity at Stratford-on-Avon, complete with Shakespeare’s tomb and a twenty-four-hour service of organ music played automatically by the Perpetual Wurlitzer and broadcast by concealed loud speakers all over the cemetery…

I now have a new item on my to do list for my next trip to the Chinese mainland: see if any of the bookstores there I have visited in the past stocks a translation of After Many a Summer Dies the Swan. It seems as though it might well speak to some issues of the day. In addition, its surrealist nature might appeal to the same Chinese readers drawn to One Hundred Years of Solitude, which has sold well in China. Chinese familiar with Huxley’s Brave New World might also enjoy it, as even though After Many a Summer Dies the Swan is set in what was then present-day American rather than in the world of the future, it contains a similar concern with issues of hedonism and social stratification.

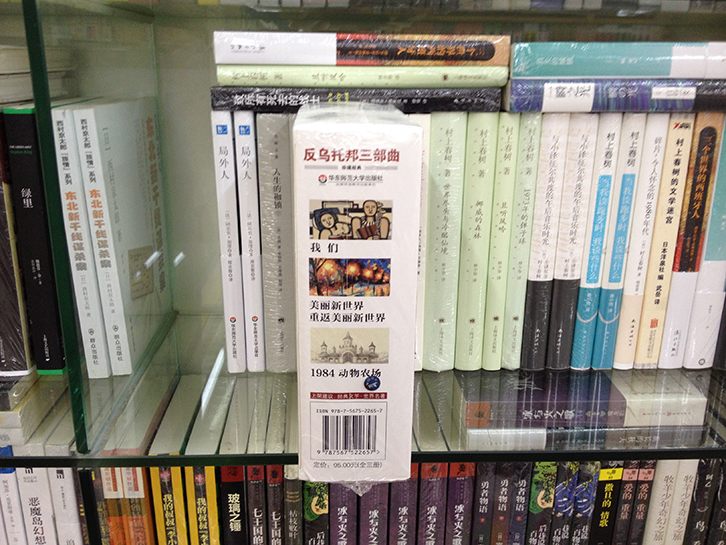

One thing I discovered while shopping for books in China last year is that Brave New World is available in two different Chinese language packaging. Not only can you still buy a translation of it standalone volume, as you have been able to for year, but you can pick up a three-volume dystopian classics value pack that includes it. One of the volumes in this set is a two-in-one George Orwell pair, with Nineteen Eighty-Four and Animal Farm bundled together. Another is a Huxley combo: Brave New World combined with Brave New World Revisited, a non-fiction work written in the 1960s that assesses trends that the author saw as confirming to or suggesting the need for modification of the predictions he had made in the early 1930s. The third volume is Yevgeny Zamyatin’s We, a 1921 Russian work that is often described as a major precursor to and influence on the writing of both Brave New World and Nineteen Eighty-Four.

It is interesting to note the ability of people living in a country still run by a Communist Party to buy this value pack, made up as it is of works that satirize in different ways collectivist states and totalitarianism. And though I have only dipped into rather read closely the Chinese language texts it includes since buying the set at a Shenzhen bookstore in 2014, the translations of the novels, at least as far I have been able to determine, all seem unexpurgated.

This is not the case, however, with the one non-fiction work in the collection Brave New World Revisited. In the English language version, Huxley includes a section on brainwashing that refers to things being done in the People’s Republic of China. Those and other sections that specifically refer to China have, not surprisingly, been left out of the Chinese language edition. It is one thing to allow readers to make up their own minds about whether an allegorical dystopian work could be relevant to the country in which they are living, quite another to have a writer come right out and say that China in Communist Party rule had become a place where some things Huxley wrote about as part of a nightmarish possible future had actually been realized.

One reason I secured a copy of the new Inspector Chen novel was that I thought that after reading it I could see if Qiu would do an author Q & A for this blog. After reading the opening chapters, I know I will want to do that — and that one thing I’ll ask is which if Huxley novels he has read. He may find it odd that I’d bring up an early 20th century Western author who moved in the same circles as Virginia Woolf in an interview about a novel set in today’s Shanghai. If he doesI’ll remind him that he begins his latest book with a nod to a famous line by someone other than Huxley who fits into just that category. “April is a cruel month,” Shanghai Redemption begins, “if not the cruelest.”

This bit of allusive word play paves the way for a short disquisition on the most important Chinese holiday relating to the dead falling in early April. And that’s just the sort of toggling between cultures to be expected from Qiu, a Shanghai-born but now St. Louis-based author whose protagonist is so attached to the work of T.S. Eliot, who was born in St. Louis but lived most of his adult life in London. The poet and Huxley moved in related circles in England — until, that is, the latter crossed the Atlantic in the other direction in the 1930s, choosing to live out the rest of his days in the consumerist California whose foibles he satirized so brilliantly in After Many Summers Dies the Swan.