Photos by Peter Merts, courtesy of the California Arts Council. www.artsincorrections.org.

I spent several days of this very hot summer visiting and teaching art in prisons across the state. From Fresno in Central California to Chino in the Inland Empire, down to Blythe on the border with Arizona and across the desert to Calipatria on the border with Mexico, many prisons are located in desolate places. Fields and farm stands surround some, while the most remote lie in the distant desert, nearly two hours past Palm Springs and 45 minutes from the nearest gas station. Arts in Corrections programs are located deep within layers of concrete and metal, through barbed wire and behind multiple gates guarded 24-7 by officers that slam and lock behind passersby. The location and structure mirror the distance and isolation of the individuals that live there, many for decades. Yet a kind of freedom is found — in makeshift classrooms, gyms, and dining halls — through creative arts.

On this trip, I was traveling south to teach classes and attend end-of-term certificate ceremonies with our Prison Arts Collective. I tend to teach my classes in correctional institutions over the summer when I’m not teaching on campus, which coincides with the hottest months; temperatures in Blythe and Calipatria reach 120 degrees on a regular basis. We come and go, yet I feel for those that live there, both in the institutions and in the community. I lead our Arts Facilitator Training, an intensive teacher education program to support incarcerated individuals with artistic skills to gain the theoretical and practical knowledge to lead classes for their peers. In the process, we have seen that students gain knowledge about themselves, society, education, and community development. I was inspired to lead this class from meeting so many men and women behind bars that have honed their artistic practices over the years and want to give back. I wanted to share the content that our teaching artists learn in college courses and in our training to empower participants to be leaders and mentors within the institution and support their personal development.

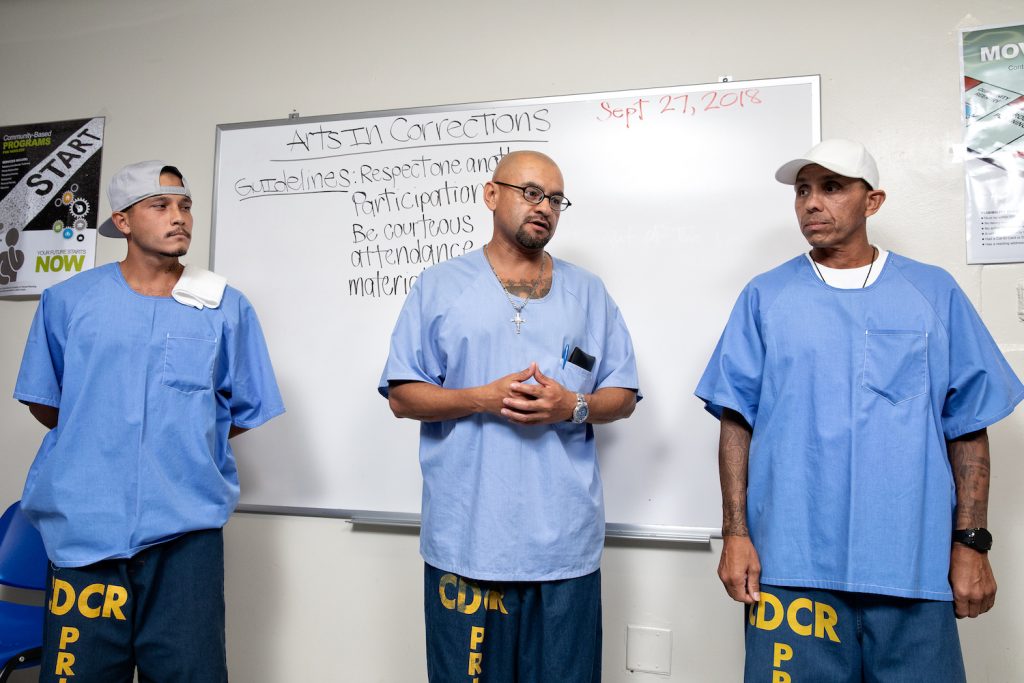

What I love about this particular class is that students start out with something that they know well — drawing, painting, guitar, poetry — but rarely with any sense of themselves as mentors or leaders, and throughout the course gain the knowledge, confidence, empathy, and leadership abilities to effectively teach their art form to others. We talk about learning theory and art interpretation. Students reflect on why they want to teach and how they will guide those with different backgrounds and levels of artistic experience from their own. We practice cultivating a positive environment in which everyone feels heard and shares experiences, both positive and negative, from our own educational backgrounds. Prior to graduating and facilitating classes, participants must complete a final project. Like most students during finals, they are typically nervous. They assignment is to develop and teach a 15-minute lesson for their peers and us teachers. The lesson can be on any art form but must engage the students and include all three elements of our curriculum: art history or culture, creative practice, and reflection.

We have taught this class six times now and each time, students anticipate the final with eager and nervous excitement. Many have never spoken in front of a group before entering this class. For some, this has constituted their first positive experience in any classroom setting. On the day of the finals, we give the classroom over to the participants and ask them to lead us through their lessons. For at least six hours, they stand up, singly or in pairs, and take us through their planned lessons in guitar or creative writing, painting, or drawing. They often surprise themselves with their success in this endeavor. To allow time for everyone, these carefully timed lessons unfold in rapid succession, one after another, with 15 minutes for the lesson followed by five minutes of discussion before the next student gets a turn.

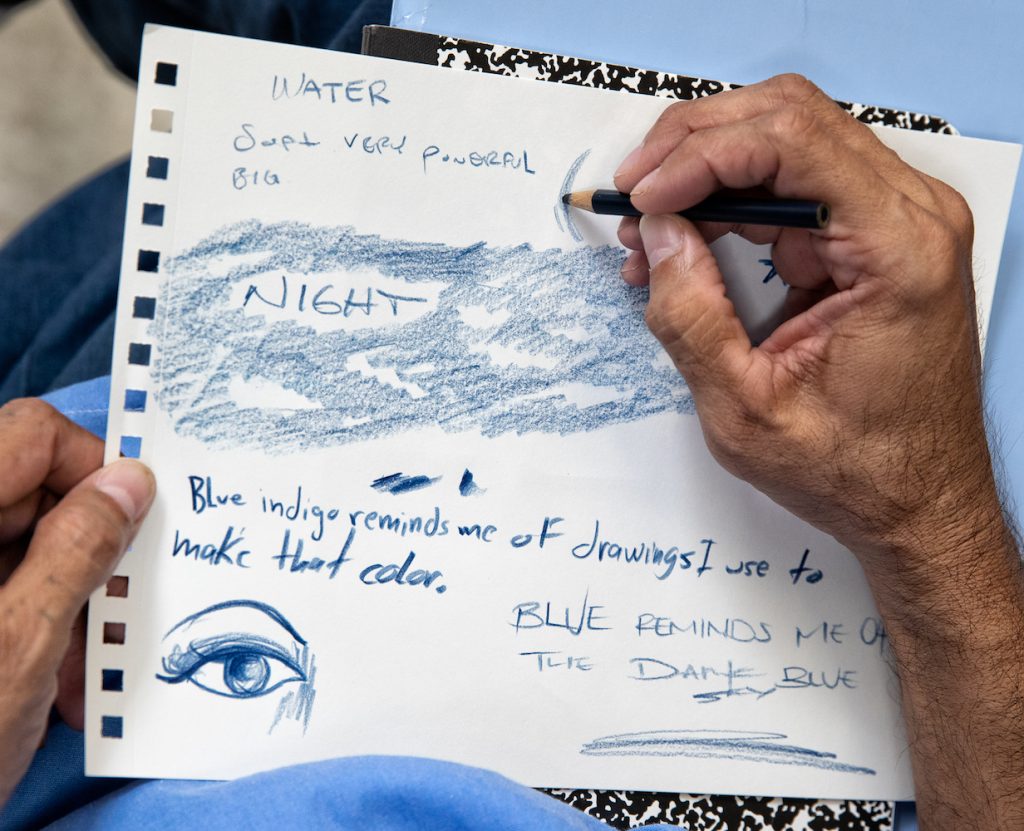

Over the summer, three groups completed their final projects. They presented to me, two members of our teaching team, and about 15 facilitators-in-training. In one room, we sat in old-fashioned school chairs, the kind with a wooden desk that attaches to the chair with a metal bar and curves around to the front. In another, we sat around table arranged to face the crowded front of the classroom. In the third, we arranged the desks in a U formation in front of a large window overlooking a cement patio and a dry mountain range. It’s nearly impossible to choose which of these innovative and hard-won lessons to share. Throughout, we were led through a history of choirs and a round of “Row, Row, Row Your Boat;” we stretched to find the correct finger placement on improvised guitars, the neck drawn on a sheet of paper with labeled strings, and experienced a few variations of the introductory drawing lesson, shading a sphere. We learned about the invention of postage stamps and were guided to create personalized stamps of our own. We wrote acrostic poems and haikus, reflected on memories, poetry, and art.

In one innovative lesson, a young man and former graffiti artist enthusiastically led us through a lesson on lettering. He shared that this art form celebrates freedom and style done at a necessarily fast pace. He shared images and led us through a step-by-step guide to make a dimensional and bubble shaped “G.” His encouraging approach and infectious enthusiasm spurred us along and I was surprised when mine came out with even a touch of the telltale pop and flare he was describing.

In another, a man that had been polite and friendly but somewhat quiet during class, shared a quote from Henry Moore about the definition of sculpture before directing us to find the image of Constantin Brancusi’s “The Kiss” in our art history reading. “We are going to make our own version, ‘The Smooch,’” he shared, to smiles and laughter. As he walked around to pass everyone a small, smooth bar of white soap, he gave a poignant metaphor about how, just like this soap, we can all change our paths or destinies. Soap is made for washing but we would turn it into sculpture.

Often, students co-teach the final project. At one point, two men stood in front of the class, a bit nervously, to lead a portrait lesson. The more outgoing of the two showed images of portraits copied from art history books, sharing that artists had made portraits since the beginning of time. The quieter man visibly gathered courage before speaking up and eloquently cites that the things we share — hopes and dreams, disappointments and heartaches — connect us. They asked us to think of someone important to us. We were to draw that person from memory and list five words to describe the person. As they passed out small pieces of paper and pencils, I thought about who I would draw and decided to sketch the image of an artist friend who had recently passed away. His memorial was scheduled in Los Angeles the night before these students’ graduation and I was leaving a day early to attend it. I had wanted to bring him to one of our classes behind walls and hadn’t ever had a chance. This was on my mind as I drew. I was so focused on attempting to capture my friend’s image and spirit that I truly became the student at that moment, a shifting of roles on many levels and one that I value.

Some lessons integrate rehabilitative skills that students have learned in other classes with the art and community building from our training. A pair of students planned to teach card making, a vital skill for those with little access to families and friends, and demonstrated how to draw a cartoon character (Winnie-the-Pooh) for their final, a first step to making a pop-up card to send to children, nieces, or nephews back home. Some students in our first Arts Facilitator Training applied what they had learned in a lifer’s group to their growing awareness of art and community to create a meaningful course in Creative Writing and Amends. They invite students to reflect on works of art and writing to build empathy and complete journal entries designed to help them to reframe past experiences and gain a new perspective. Another peer facilitator evolved what he learned about art interpretation into a fascinating class that invited his students to consider how interpretation — of events and actions and words — can change our understanding and point of view, deftly applying art criticism to valuable life skills.

Over the past year, this class has grown and our first peer facilitator graduates are now leading classes in poetry, drawing, music theory, painting, art history, and more. It is gratifying to visit the programs and see how they collaborate to cultivate a positive environment and support their students. In one recent session, a serious young man was leading a session in art appreciation. He is also taking college classes at the institution and had asked to borrow our art history book to develop his class. On the day I visited, he led a lesson about the Renaissance, sharing that it meant “rebirth.” They looked at images of art from the time period and then drew their understanding of rebirth. As they shared their drawings, each had independently tied the concept of rebirth to the new life that they will embark on after prison.

Another final project featured a landscape drawing. The pair leading it showed a landscape by Van Gogh and shared a bit of his biography before asking us to imagine a window. “You know how there are windows in our cells,” one of them began, “but they are painted over? Imagine that you scratched away a tiny square from that window and could peer through it. What landscape would you like to see?” This idea of a painted over window, with a tiny scratched out square, was moving. As I attempted to draw it, I noticed that the room had grown particularly quiet. I paused to look around. Fifteen students in prison-blue and two teaching artists, all in black, were bowed over their work, each lost in a distant memory or cherished dream, interconnected in the experience of re-envisioning and re-creating a sense of place.