This is my first visit to our new program at this prison. I meet up with our teaching team in the expansive parking lot and we walk through a sea of cars to a small guard booth where an officer is sitting behind a Plexiglas screen. He greets us, already familiar with the four teachers that have visited for the past four weeks. They sign in, introduce me, and we are issued a key and alarm. The process is relatively easy, calm, and methodical.

One thing I have noticed through my work facilitating art in prisons is that nothing much is rushed inside a prison. This took some getting used to at first — our worlds outside these walls tend to move quickly, with so many deadlines, and so much to do. Organizing programming to occur inside a state prison is one of the most complicated logistical endeavors that one can imagine — but no matter how many necessary lists and emails, texts and phone messages, contracts, syllabi, and meetings occur to allow this work to happen, they don’t carry the same weight on the inside. Once all the preparations are complete and we are here at the gate, at the edge, all of that busyness subsides and we are simply present, in this moment, checking in, clipping on our badges, storing our IDs in a safe place. We complete each task slowly, take our time, so that nothing is neglected. When this process is complete, I follow our team along a winding path between chain link fences and through multiple gates. We pass a second check-in station, where we show our identification again. One at a time, we show our card and look into the eyes of the correctional officer. He looks directly back, studies each face momentarily, then down at our ID and back before handing the ID back, sometimes with a smile, rarely with much discussion.

We have been entering and working in prisons for a few years, leading weekly art classes, but we are still outsiders compared to those who work here daily, many for decades, and even more so to those who are housed here. We are keenly aware that we are visitors to another — not so much “world” — but, another place, with its own culture. When we are here, we consider ourselves as if we are guests in another’s home. We follow the customs and rules, both written and, to the extent we have grasped them, unwritten.

When we arrive at the space where our classes take place, I’m pleased with the room we have been allowed to use here. It is like a classroom or a small working studio. Our teaching team, consisting of three teaching artists, all alumni from the program that I oversee at our university, together with one current student intern, get right to work. They have prepared supplies in clear plastic bins, each carefully labeled with lists of the contents: 12 pencils, 12 erasers, six sets of markers (12 markers each), six brayers, one tube of red ink … and so on. Before passing out any supplies, they must be ordered and counted in this way. At the close of each session, all of the same supplies must be collected and returned to the boxes. This process, too, is slow and methodical; teaching inside a prison is by necessity an exercise in mindfulness.

After a short time, the men begin to arrive. A correctional officer is standing at the door. He greets each of the men as they enter, giving each man a quick look up and down before waving him into the room. The process is orderly and the men seem relaxed and happy to be here. Most of all what I notice are the smiles, so many smiles. At this particular prison, many of the participants are somewhat younger than in some of our other programs. They are in their 20s, 30s, and maybe 40s. I’m not sure if that contributes to the focused, happy, and more classroom-like atmosphere of this particular site, or if it is more the space that we are using that lends itself to being a school-like environment.

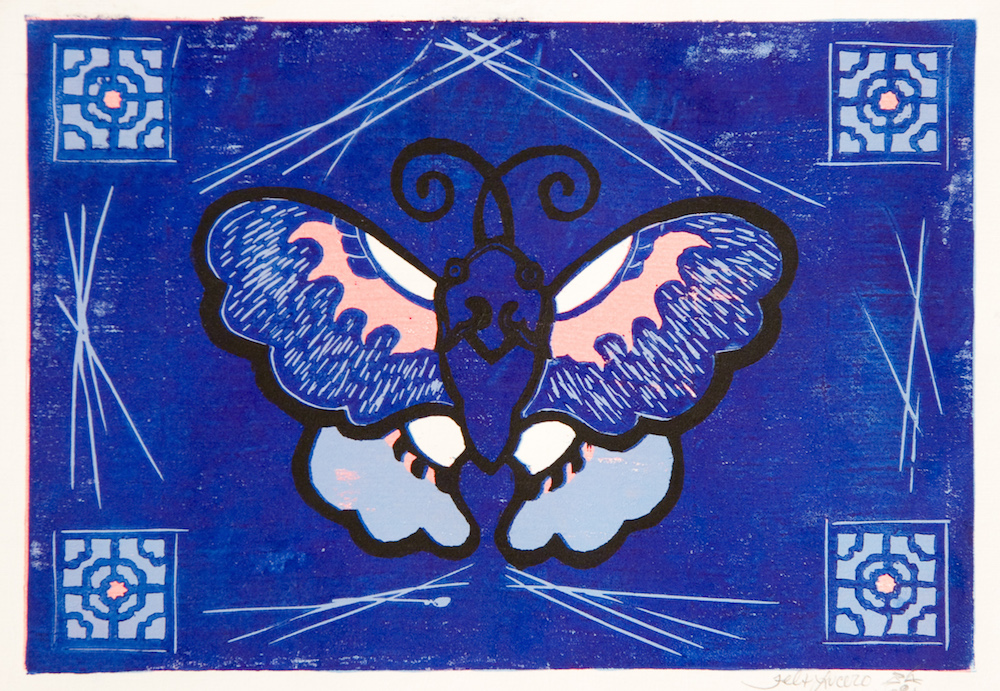

The men arrive gradually, in small clusters. As they do, they find their seats at their respective tables, already having selected which class they will be participating in for the session. The teaching artists are divided into teams of two to lead their classes, one in printmaking and the other in patterns around the world. In this latter class, the the men are introduced to cultures through a short reading and then shown artwork, specifically artworks influenced by pattern, from that culture. From there, they are invited to create an original work of art inspired by the pattern and culture. They looked at Japanese art last week and, as we wait for class to begin, some of the men show me their work: one shyly holds up a beautiful and highly detailed rendering of a blue fish with delicately patterned scales; another shows me a painting of amorphous and repeating red shapes, still in process, still being worked out.

As more men arrive, our Site Lead begins the session. She welcomes everyone back says that she is happy to see them before sharing the schedule for the day and introducing me. I sit down at a table near the door with a group of four men who are in the printmaking class and ask if I can join them in the first group activity. Their response is relaxed and gracious; they welcome me to the group. We are guided to sit back in our chairs and either close our eyes or look at one spot. We close one hand into a fist, and then, one by one, breathe in, pause, and breathe out, pause, and open one finger. We are guided to do this with each finger of the hand until we have taken five conscious breaths, generating a sense of relaxation that is visibly mirrored in our now open palm. I feel a gentle smile coming across my face and see the same on the faces at my table. What began as bubbling and almost boisterous energy throughout the room has settled into a more grounded and focused atmosphere. From here, we are asked to create five small drawings and write five words. I know this activity well and have taught it often, but I have not sat and participated in this way, with men that I have not met before and in this new space. I make five small squares on my paper. I look at the table around me. Most of the men have done this before, but it’s new for some, and they’re unsure what to draw. We talk a bit amongst ourselves, hoping to give one another ideas for the sketches. I suggest we look around the room. Another man explains that he is making sketches for a painting that he wants to work on.

Sometimes, through art, we have the opportunity to gradually ease the strict barriers that necessarily exist between inside and outside. The individuals that are incarcerated, whether temporarily or for life, severely lack opportunities to interact in the typical ways that we take for granted — what we might consider a casual greeting in a grocery store line becomes an exchange layered with meanings I can’t begin to understand on the inside. But all of that is left outside the art room and we have an opportunity to engage in another kind of interaction: artistic, educational, intellectual. We do not come here to chitchat — that is not our role — but rather, through art, a very particular conversation unfolds, whether inside or outside, that involves the technical language of color and line and shading as much as the interpretive discussion of meaning and possibility. I think some of the magic of facilitating arts programming inside prisons is the fact that, despite all the preparations and all the gates, the rules and limitations, the art experience itself is not so very different as it is on the outside. That such strict borders between us can be rendered invisible for even a period of time through art is a kind of alchemy.

After a short time, another man joins our table. He arrives late and is wearing a blue watch-cap. We welcome him and explain that we are on the drawing part of this three-part exercise. He is assigned a pencil, given a piece of paper, and gets right to work. But something about the man seems less pleasantly upbeat than the general tenor of the room. He seems sad and self-consciously aware of his own distraction, or perhaps discomfort. I ask how he is doing, “I have a lot on my mind,” he offers. I suggest that he could do the breathing part of the exercise to help get into the frame of mind for art but, he explains, the practice is new for him and he is not familiar with how to do it. One man at our table suggest that we do the breathing with him. I think that’s a great idea and suggest that, this time, we try all 10 fingers rather than just the five on one hand, to offer something new for those that just did this. They are up for it.

We close both fists. Some of us close our eyes and others among us gaze at one spot with soft eyes, unwilling or unable to close our eyes in such a space. We take a breath in, pause, let it out, pause, and open one finger. We do this again. And again. And again. We breathe in our own rhythm, each in our own time, rather than attempting to follow one leader. Some finish before others. They wait, calmly. Once again, the space feels more peaceful after the interlude, as if the air around our table had expanded. The man in the cap is one of the last to finish. Afterwards, I ask him if it had helped. He nods. “Yeah,” he says softly, with a small smile.

By now, the printmaking teaching artist has introduced the artwork we will be discussing for the day and the project that they will be creating. I leave my small group to work on their prints and walk around the room. I talk with participants in the other class about the cultures they have learned about so far and listen in as they read aloud about the Māori culture. “The Māori originated with settlers from eastern Polynesia, who arrived to New Zealand in waves of canoe voyages at some time between 1250 and 1300 CE…” The men volunteer to read aloud. One has the rich and resounding baritone of an actor. Some stumble on a few words and the others help them.

I make my way back to my table just about the time a moth flies in and lands on one man’s paper, fortunately managing to miss the sticky ink. The man in the hat says, “Wait, don’t hurt it.” He gets up from his seat, walks to the other side of the table, and carefully scoops the baffled moth in his open palm, cupping the other hand over it, and then walks to the open door and gently places the moth just outside.

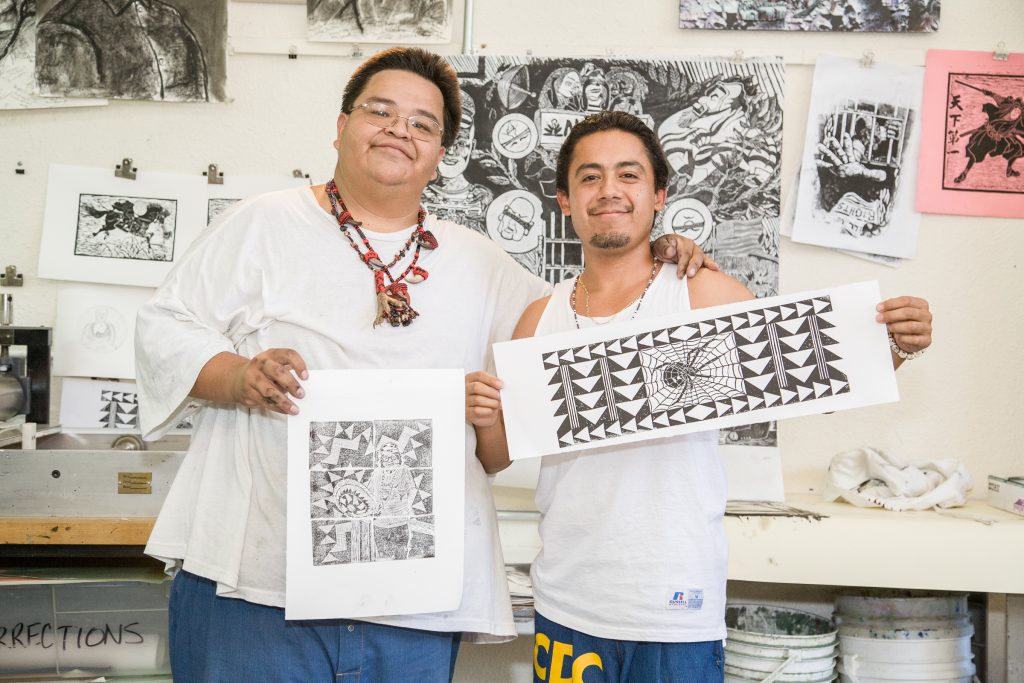

For the last portion of the class, all the artwork that was made that day is taped to walls and laid on the tables so that everyone can see and discuss what was created. The teaching artists guide a discussion, encouraging everyone to look at all of the artwork and to talk about what they see — what stands out, and what they think it means. One of the men begins to discuss a print with a vibrant orangey-red texture on one side and a dark structure on the other. “It’s got symbolism,” he says, “see, that’s fire and steel on the sides and there is a heart melting in the center. And that’s family and love. They give you strength through the ups and downs.”

I notice a print up on the wall with a detailed depiction of a small child wearing a backwards baseball cap sitting with his arms hugging his knees. The child is drawn in a sweet cartoonlike style and placed in the lower right hand corner of the paper. All around and above the child is empty space, the color blue. I ask who made the print and the man next to me, the man in the hat, says it was his. I explain why I like it, the way that the sweetness of the drawing contrasts with the openness of the space. He seems pleased. The conversation winds down and everyone begins to clean up. Like everything else in this process, this is a slow and methodical endeavor. But eventually each pencil and brush and brayer is carefully returned to its clear plastic bin. I see the man in the hat before he leaves and ask him about the drawing. He says of the boy in the picture, “He’s missing his dad.” I hope, if he has a son, that he will send the picture home to him.

Images by Peter Merts