“55 Voices for Democracy” is inspired by the 55 BBC radio addresses Thomas Mann delivered from his home in California to thousands of listeners in Germany, Switzerland, Sweden, and the occupied Netherlands and Czechoslovakia between October 1940 and November 1945. In his monthly addresses Mann spoke out strongly against fascism, becoming the most significant German defender of democracy in exile. Building on that legacy, “55 Voices” brings together internationally esteemed intellectuals, scientists, and artists to present ideas for the renewal of democracy in our own troubled times. The series is presented by the Thomas Mann House in partnership with the Los Angeles Review of Books, Süddeutsche Zeitung, and Deutschlandfunk.

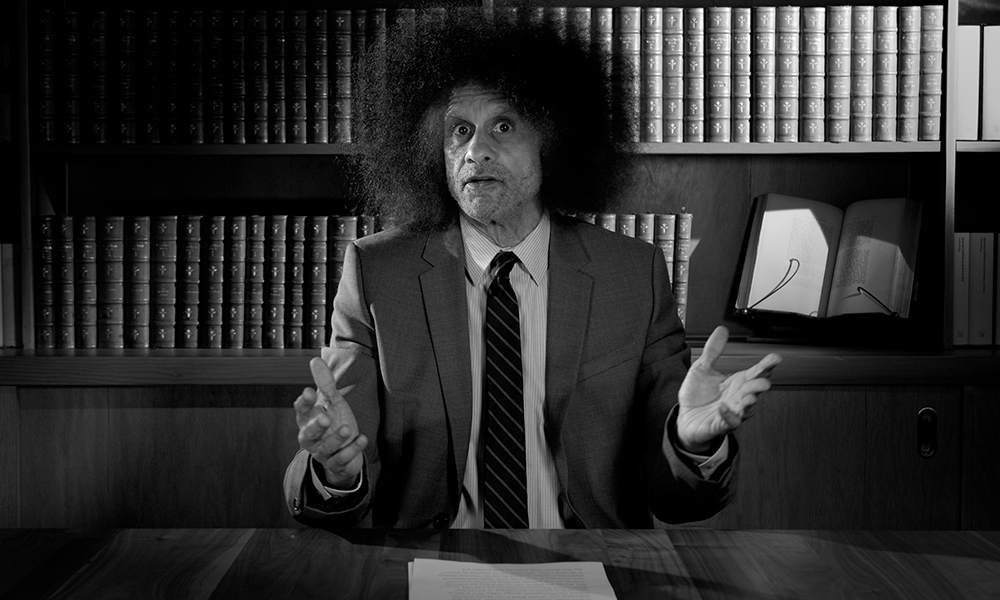

The video of Jody David Armour’s talk can be viewed below.

¤

Effective political communication is the beating heart of democratic social justice movements. Given that undeniable fact, should Black Lives Matter activists seeking transformational change soften their political messaging to appeal to the majority of Americans? When former President Donald Trump told NFL owners they should fire players who kneel during the National Anthem, he was actually speaking for most Americans who, according to polls at the time, supported requiring professional athletes to stand during the National Anthem at sporting events. The battle cry of “Defund the Police” has also drawn sharp criticism from pundits and politicians as too extreme or radical or militant or triggering to be a useful political tool.

Given the widespread disapproval of the protest tactics and messaging of grass roots organizers and their allies and accomplices, it is fair to ask whether these forms of political communication hurt the cause of racial and social justice more than they help. I always get this question. Does the disapproval a certain protest tactic or rallying cry generates in the general public make it an ineffective tool of social change? Or does the tactic’s or slogan’s efficacy lie in the very fact that it is provocative, disruptive, and unpopular? Politically active players and grass roots activists alike can take heart from this country’s history of looking down on the tactics and messaging of an earlier generation of civil rights activists whom history has vindicated.

Although activists in the civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s are generally held in high regard today (Rosa, Martin, Medgar, and countless unsung activists), polling data from the 1960s show that the majority of Americans felt such protest actions (sit-ins, freedom rides, marches) would hurt, not help, the black struggle for equality. A 1961 Gallup poll found that 57% of Americans felt the freedom buses, sit-ins at lunch counters, and similar tactics by blacks would hurt their chances of being integrated in the South. Only 28% of Americans thought these actions would help (and 16% had no opinion). Just before the 1963 March on Washington where Martin Luther King gave the famous Dream speech, Gallup asked a representative sample of adults about the planned protest, and only 23% said they viewed it favorably. In 1964, nearly three-fourths of Americans told Gallup that mass demonstrations by blacks were more likely to hurt than help the fight for equality. A 1966 Harris survey of whites found that 50% believed King was hurting the “Negro cause of civil rights,” while only 36% thought he was helping it (with 14% not sure).

Recognizing the deep opposition to the civil rights movement’s tactics in its day — tactics viewed as useful and necessary today — may help current-day Americans resist hasty condemnations of the tactics and slogans of this transformational new civil rights movement we now find ourselves in the midst of.

One form of potent political messaging that many blacks participated in at the height of the George Floyd protests last summer was the observance of Juneteenth, an annual celebration marking the day enslaved Black people in Galveston, Texas learned that they had been emancipated. Put differently, Juneteenth is the date many black folk have chosen to celebrate the official deliverance of black bodies from America’s bondage.

When I think of black bodies in America’s bondage, I first think of my own father — a six foot eight-inch barrel-chested black veteran of the Second World War and proud Marine who, in the words of America the Beautiful, “more than self his country loved.”

This fact baffled me for years. I couldn’t fathom a black man like my father pledging allegiance to a flag, and the nation for which it stands, after that very same nation showed its gratitude for his military service by throwing him in a cage in a state penitentiary for 22 to 55 years for alleged possession and sale of marijuana. How, I used to wonder, could he and other black victims of intolerable racial oppression in America perjure themselves again and again with the fiction of nationhood?

Dad taught himself the law in prison and found the key to his cell in the warden’s own law books, vindicating himself in a case I now teach in my criminal law class called Armour v. Salisbury; but his wrongful conviction took a terrible and ultimately lethal toll. I could only attribute his unflagging love for “his” flag, his undying zeal for his own captors and their emblems, to some kind of psychological disability — say, Stockholm syndrome — in which victims sympathetically identify with and even celebrate their abusers.

In time I came to see his patriotic devotion to the American flag not as a mental illness but as a profoundly political act, one intimately wedded to Juneteenth and the malleability of meaning in matters of political communication.

The United States Declaration of Independence, adopted by our nation’s founders in Philly on July 4, 1776, pronounced that “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.”

These were exhilarating promises and aspirations, but in their deeds the men who wrote and adopted that Declaration did not live up to their lofty language, for many of them bought and sold black bodies like mine on auction blocks in open markets across this nation.

The “us” that the American flag originally stood for — it’s original “meaning” — did not include folk like me, who, according to the Supreme Court’s 1857 Dred Scott decision, “had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.” It took 600,000 dead men in a cataclysmic race war to transform the meaning of the American flag into an emblem that includes black folk in its “us” of American citizens.

The words of the Declaration of Independence became relevant to Juneteenth, their meaning changed radically, when, in his Gettysburg Address, President Lincoln thought about the graveyard his country had become, and, echoing that foundational Declaration, said, “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent, a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.’

That new nation that Lincoln pointed to is the nation that inspired my father and which Juneteenth celebrates.

And then Lincoln uttered these words that have burning relevance for the generational upheaval we are witnessing in this country today: “It is rather for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us — that from THESE HONORED DEAD we take increased devotion to that cause for which they gave the last full measure of devotion…” That cause, the cause of racial equality and freedom for black people in America, is the cause, the animating spirit, that drives today’s marchers and protesters and freedom fighters.

My father knew that the flag he bled for once stood for slavery and Jim Crow, but he also knew that meanings are not fixed and frozen. Rather, they are prizes in pitched conflicts among social groups seeking to define their social identity, vindicate their social existence, and mid-wife a more just world.