Few readers in Korea seem to lack an opinion about Kim Ji-young Born 1982 (82년생 김지영), the best-selling novel in the country last year. The first book by Cho Nam-joo, a 39-year-old former television scriptwriter who quit her job after her daughter was born, it tells a story at first engineered for a maximum of normality: the title character grows up, goes to school, gets married, gets a job, and like the author leaves that job to become a stay-at-home mom once she has a baby. In another experience shared with her creator, Ji-young strolls her daughter out to a coffee shop only to overhear a few office workers refer to her as a mam-chung (맘충), or “mom-worm,” the kind of demanding, child-toting, deeply entitled woman some Koreans have come to see as a kind of modern menace.

The novel has drawn so much attention because of the frank manner in which Cho renders the countless indignities visited upon Ji-young in her still-short life, from the fact that her own mother had hoped for a son instead to being told that the boys who pick on her in school must “like” her to fellow bus riders’ reluctance to give up their seats for her during her pregnancy. The final straw comes when she has to cross the country to cook an elaborate feast for her husband’s family, just as she does every year of her married life, for the Thanksgiving-like Chuseok holiday. Ji-young suddenly snaps and demands to know why she can never spend Chuseok with her own family back in Seoul, but she does it in the voice of her mother, one of the succession of personas that overtakes her as she plunges into a kind of insanity.

To this extent Kim Ji-young Born 1982 has much in common with Han Kang’s The Vegetarian, winner of the 2016 Man Booker International Prize in in Deborah Smith’s English translation, a novel whose thirtysomething female central character rebels against Korean society’s expectations by refusing to eat meat. This leads into a series of other increasingly eccentric behaviors, culminating in an intensely focused effort to live as a plant, whereas Ji-young remains essentially a recognizable everywoman right down to her name (anyone who spends much time in Korea will meet a Kim Ji-young sooner or later, and probably more than one) and the footnotes with which Cho documents the statistical basis of her averageness. “I feel like this is a story of a real Kim Ji-young living somewhere,” Cho writes in the novel’s prologue. “Her life resembles very much that of my friends, colleagues and of myself.”

Even given the psychic damage cumulatively inflicted on Ji-young by existing while female in South Korea, one suspects that many a woman from the less developed countries of Asia would take her place without a moment’s hesitation. (The lives of women who immigrate here in order to do more or less that, and especially their turbulent relationships with their Korean mothers-in-law, provide abundant material for television documentaries.) Even in America a fair few women might find Ji-young’s situation — still young, well-educated, non-impoverished, father of her child in the picture, no opioid habit — not entirely unenviable. Despite the novel’s artistic strengths, its inevitable translation into major languages will, alas, do little to remedy modern South Korea’s reputation as a nation of whiners.

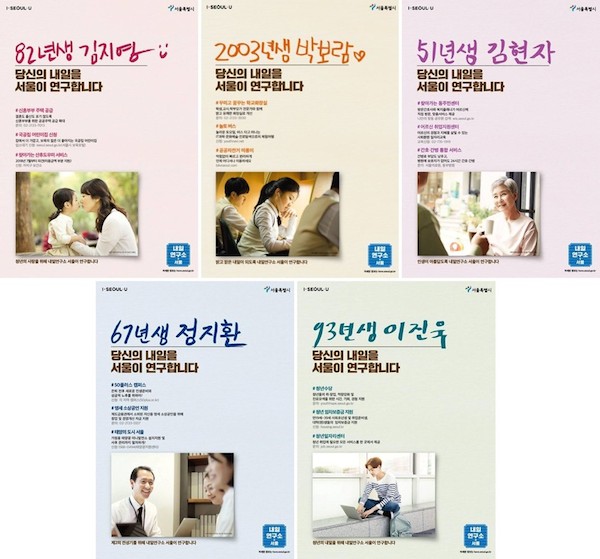

Nor will the reaction to a recent public-relations campaign by the Seoul metropolitan government that makes clear reference to Kim Ji-young Born 1982 and its newfound place in the Korean zeitgeist. At the end of March, a series of posters went up all over the city promoting “Future Laboratory Seoul” (내일연구소 서울), the name bannering a series of programs geared toward assisting citizens of various ages prepare for the next stage of their lives, whichever stage that may be. Each poster lists a few of the services available to one particular generationally representative figure with a generationally representative name: Kim Hyeon-ja born 1951, Jeong Ji-hwan born 1967, I Jin-uk born 1993, Bak Bo-ram born 2003 — and yes, Kim Ji-young born 1982.

The programs open to the city of Seoul’s white-sweatered vision of Cho’s character, and presumably the similarly dressed daughter she holds aloft, include housing provision for newlyweds, postnatal caretakers, and subsidized daycare. This, along with the fact that the designers used pink and orange for the female posters and blue and green for the male, drew the campaign immediate and harsh social-media criticism for reinforcing gender roles — and what’s more, completely missing the point of the novel whose title it borrowed. The Ji-young of the book, though, could have used such governmental offerings, the cost of child care being what forces her to quit her job (at, incidentally, a public-relations firm) in the first place. But then, in Cho’s telling, she dodged at least one in Korean sexism’s hail of bullets by leaving the company: a peeping-tom security guard installs a hidden camera in the women’s bathroom soon thereafter.

Kim Ji-young Born 1982 turned into a cultural phenomenon before Korea’s “#MeToo Moment” started in earnest, in part on the back of celebrity recommendations. Ironically, one of the book’s well-known readers, South Chungcheong province governor An Hee-jung, recently abdicated his position (and status as a “rising political star”) in the face of sexual misconduct accusations of his own. In such a social climate it comes as no surprise that one group launched a crowdfunding drive for a book called Kim Ji-hoon Born 1990, a kind of parody of Cho’s novel in which a young Korean man realizes he’s wasted his most precious years putting in mandatory service in the South Korean military while the women of his generation, not subject to the same requirement, were out there getting a head start on life. Though the project ultimately ended up withdrawn, it had already made its statement, and one that at least critiqued a specific institution.

But whether Kim Ji-young Born 1982, Kim Ji-hoon Born 1990, or any of the associated reactions and discussions, all in some sense draw from the conception of 21st-century South Korea, increasingly widespread within the country, as a species of hell. Jang Kang-myoung’s Because I Hate Korea (한국이 싫어서), another popular novel about a dissatisfied female published the year before Cho’s, approaches more directly the idea of South Korea as uniquely unable, among developed countries, to furnish the conditions of a satisfying life. But man or woman, Korean or otherwise, one surely doesn’t have to take too hard a look at the rest of those developed countries to realize that things, as a couple American sages of our time once put it, are tough all over.

Or to quote to a voice a little closer to this part of the world, Kim Ji-young Born 1982 brings to mind, as The Vegetarian did, the words of Elizabeth Costello, J.M. Coetzee’s feminist novelist and militant non-animal-eater from Australia (the destination of choice, incidentally, for the young woman in Because I Hate Korea). “I seem to move around perfectly easily among people, to have perfectly normal relations with them,” she says in the novel that bears her name. “Is it possible, I ask myself, that all of them are participants in a crime of stupefying proportions?” Every day she sees the evidence in the form of the “fragments of corpses that they have bought for money,” and if only they all saw reality as clearly as she does, she seems to believe, their crime of meat-eating would cease. A dubious proposition, to be sure, but Elizabeth Costello wouldn’t be the first novelist to believe in the curative powers of her own worldview.

Related Korea Blog posts:

The #MeToo-ing of Ko Un, Korea’s Best Hope for a Nobel Prize

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall hosts the Korean-language podcast 콜린의 한국 (Colin’s Korea) and is at work on a book called The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. You can follow him at his web site, on Twitter @colinmarshall, or on Facebook.