The following article is the third in a five-part series about the movement at the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. The mobilization, of people and resources, which was spurred on by the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline, began an unprecedented convergence of hundreds of Indigenous Tribes, and thousands upon thousands of people. The series, which was originally written as a single piece, offers the reflections of Brendan Clarke, who traveled to Standing Rock from November 19th through December 9th to join in the protection of water, sacred sites, and Indigenous sovereignty. As part of this journey, which was supported by and taken on behalf of many members of his community, Brendan served in many different roles at the camps, ranging from direct action to cleaning dishes and constructing insulated floors. He, along with the small group he traveled with, also created a long-term response fund, which they are currently stewarding. These stories are part of his give-away, his lessons learned, and his gratitude, for his time on the ground.

POST THANKSGIVING LULL

After Thanksgiving, people left in droves. Winter rode in on the back of a snowstorm, and the temperature dipped below freezing, where it would likely remain for the rest of winter. Routine set in, as much as such a thing can in a place and time as uncertain and changing as Standing Rock.

Every morning, well before the pink light graced the hilltops, a man’s voice would come over the PA system, “Get up! It’s time to pray. It’s a beautiful day. Get up! This is what you’re here for. We’re not on vacation.”

Slowly, fumbling in the dark for a headlamp, I would begin the long process of getting dressed with layer after layer after layer. Then, along with others who were awake and dressed, I would make my way to the Sacred Fire next to flag road. By then, the wake up call had turned to song and prayer, which sometimes lasted more than an hour. As the singers sang, and the elders prayed, the sky would turn pink over the hills east of the Missouri, this long river who had called us all here. Then Beatrice, a clan mother from Michigan, would begin a water blessing ceremony. The heartbeat of the ceremony was a song that was so familiar in its melody, but not its words. As the story finally came forward one day, it was the same water honoring song that Paul Raphael taught the women back home, only it had been translated into Lakota when the Lakota children performing this water ceremony asked if they could sing the song to the waters in their own language.

After blessing copper vessels full of water in a brief ceremony, we would walk through camp, along flag road, down to the edge of the Cannonball River, with the women leading the way. When we finally approached the banks of the river, the men would go ahead of the women and create two parallel lines, making a hallway of helping hands to serve the women as they navigated the steep, often snow-covered steps down to the water. The women then offered their songs and prayers. Then the men and women switched roles.

Day after day we began in this way. As the days passed, some faces remained the same, and others came and went. The ceremony began to take its own shape. People learned each other’s songs, and where and how to be. Perhaps the deepest learning in this for me was about my patterns when I would walk this line. When I began, I would use the hands when I needed them, down a particularly steep section, or when standing from kneeling by the river. But as I stood helping, I would watch some people who would pause at every person and shake their hand, look them in the eye, and connect, even if just for a moment. I made a commitment to move in this way during the remaining days while I was there. Others must have done so too, or the ceremony found more of its own shape, and this contact with each person along the way became the norm. What resulted was not simply a connection with the river, the waters, the day, and our purpose at camp, but also with these otherwise unfamiliar people from around the world. What emerged from a culture of unfamiliarity, a row of hands, but not people, was a first inkling of a shared culture of relating. And are we not all related? Do we not all come from the common ancestors in the Rift Valley, in Africa? Do we not all come from the same water, that our mothers and fathers drank when we were in utero? Do we not all come from those brave single-celled pilgrims that traveled from the ocean to the land, eons ago? This is not to say that we are the same, but isn’t it fair to say that we are all related?

The word related means to “carry again.” At first glance, this seems a bit “unrelated” to the word relatives. But in its original usage, it meant, “the ones we are carried back to after our death.” Our relatives then, are the ones who will bury us. And let us not be mistaken; it is the Earth, perhaps with the help of her human hands, who will bury us in the end. In light of this common relative, we can better hear the truth — harsh, healing, and resounding — in the moment when thousands of people say, to a tiny row of police on a hilltop burial site: to our relatives on top of the hill, you are standing on the graves of our ancestors.

CEREMONIAL PROTOCOL, AND NO PROTOCAL AT ALL

After participating in the morning prayers, I always left feeling as though I could do anything, or nothing, and still be of use. It was all offered in the container of the prayers. Nevertheless, during most of the days at camp, I worked on winterization projects: building insulated flooring, tarpees (a woodstove and tarp-based shelter modeled after the tipi), roofs, wall tents, and woodstoves. On some days, I simply split and stacked wood for hours. There was so much to be done, and still, nearly every day, unless I had a multi-day project, I woke up unemployed, and in search of ways to be of use. It was easy to get swept up in the sense of busy-ness, particularly rampant amongst those who were at camp for only a few days and wanted desperately to do something during their short window. While the intention behind this desire is likely benign in so far as it does not approach the “Savior” mentality, it is not without impact. Extending out from my hallway of hands experience, I watched the different ways that people in camp related.

By nature, I look people in the eye and say hello when passing them by. As I walked around camp, sometimes searching for work, and other times for a person or a meeting place, my eyes were always also searching for the moment of greeting with another. To my surprise, a pattern unfolded based on who would meet my gaze, and who would not. To put it simply, roughly 90 percent of the time, if someone would walk past me without saying hello, or making eye contact, they were “white” in appearance. Head down, or eyes casting about looking “through” people, they were usually moving quickly, as if on some urgent task. When my searching eyes would find a person of color or an Indigenous person, I cannot remember a time when a greeting was not exchanged. I thought of Energy Transfer Partners, the company building DAPL, entering into these lands with their heads down, on their urgent task, unwilling to pause for a long enough conversation with the locals, human or otherwise. I share this not to ignite or reinforce stereotypes, but rather to seek understanding across difference. From what I can tell, this difference is more deeply rooted than the chance moments of passing one another on the road, or in the helping hands of the water ceremony. It is a difference etched into culture itself.

On many days, I found myself at California camp, cooking, cleaning, or building. I had found a home away from home there, and was explicitly told as much. The California kitchen was the largest kitchen in the camp, feeding nearly 1000 people per meal on some days. Grandma Diane, a Bishop Paiute elder, and her friend Patty, of the Hoopa nation, were at the helm. Two years prior, I had met Grandma Diane on Walking Water, when she and her tribe feasted those of us on the Walking Water Pilgrimage as we passed through Bishop. What was so remarkable to me, among much else, was the pace of the kitchen. Sometimes, the cooks and servers would circle up for nearly half an hour before a meal, to offer prayers and blessings over each other and the food. Other times, I would watch the volunteer head cook have a long and meaningful conversation with one of the grandmothers about the sacredness of life in the animals that were being eaten. And all of this was happening while a huge menu was being built out of entirely donated food that was as unpredictable as were the number of hungry mouths to feed each night.

While I was at the kitchen, I had the chance to witness two different interactions that moved me especially deeply. On the first, a Native man came to the Sacred Fire, which burned all day and all night behind the kitchen, with an offering. As it turned out, his brother-in-law had spent some time at the California camp and felt well cared for. He had recently fallen ill, and asked this man, his relative, to come and say thank you. The man did so and sang beautiful, heartfelt, family-honoring songs, to all those present. He then walked around the circle and shook every single person’s hand before leaving. It would be more accurate to say that he touched everyone’s hand, for the aggressive shaking common to western culture was not the norm amongst most Natives at the camp. On another day, as I stood in the kitchen sharing a meal with Patty, two men from the Lower Klallam Elwha tribe in the Pacific Northwest walked through the service doors. They introduced themselves, and spoke of their homeland and their ways, including their battle against the Elwha Dam to restore the native fisheries. They then spoke about how in their culture, they always took time to honor the cooks, who were responsible for keeping the people well-fed, and therefore healthy. For the next 20 minutes or more, they shared cook-honoring songs in their home language, and then proceeded to touch people’s hands and give and receive hugs. The reason for all this, they remarked, was primarily because they had been well-fed by this kitchen over the past few nights. But, as far as I can understand, there is also a deeper reason. Simply put, they were taught to do this. They were raised in a way where relatedness is not a passive role. They were raised to understand ceremonial protocol, in a culture that establishes safety not through fences, but through asking permission, relationship, and familiarity. They were taught to relate. I was reminded of Paul Raphael’s stories of when he was a child. When chided by his elders for some unapproved behavior, the words were not, “Have you no shame?” as I often heard, but rather, “Act like you have relatives.”

As these two Elwha men stood there singing, a young boy from the California camp came over and stood in front of one of them. The man looked at the boy, and then handed him his drumstick and turned his drum toward him. The boy began to play, and the man began to speak again. He shared that he likes to let little children play his drum whenever he can.

“That way,” he said, “maybe they will get the feeling of being here, and the next time we play a song, they will be up here with us.”

The man then decided to share a song “caught” by his nephew, before his nephew was even old enough to have his own drum. All the while, the young boy was beating the drum. The two men prepared to sing, the one playing his drum, while the other held his drum out for the young boy in one hand, and in the other, kept time with his hand in the air, as if playing an invisible drum. In the instant that they began to play, the young boy caught onto the drumbeat and joined them. He literally did not miss a beat. I thought of all the times when I or others I have been with have asked young people not to drum, which they sometimes seem to want to do on whatever surface they can get their hands on. My eyes filled with tears, a mix of grief and joy, at the different way that I beheld.

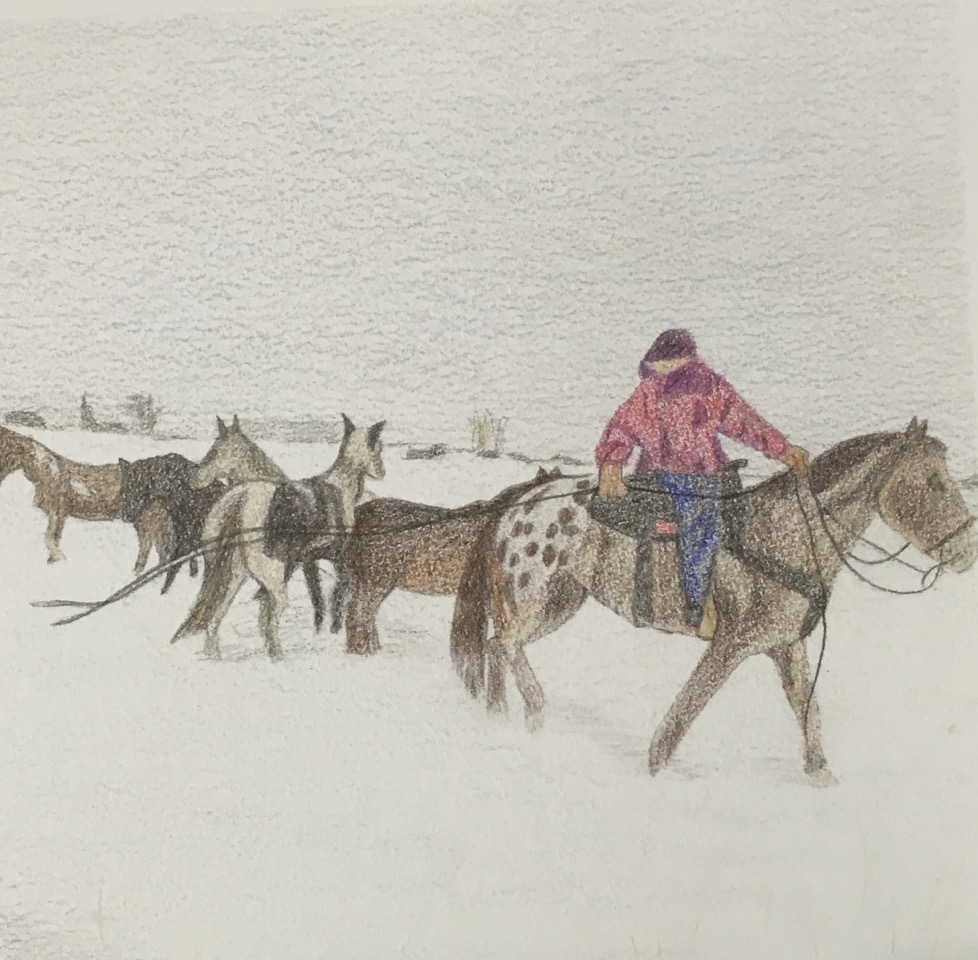

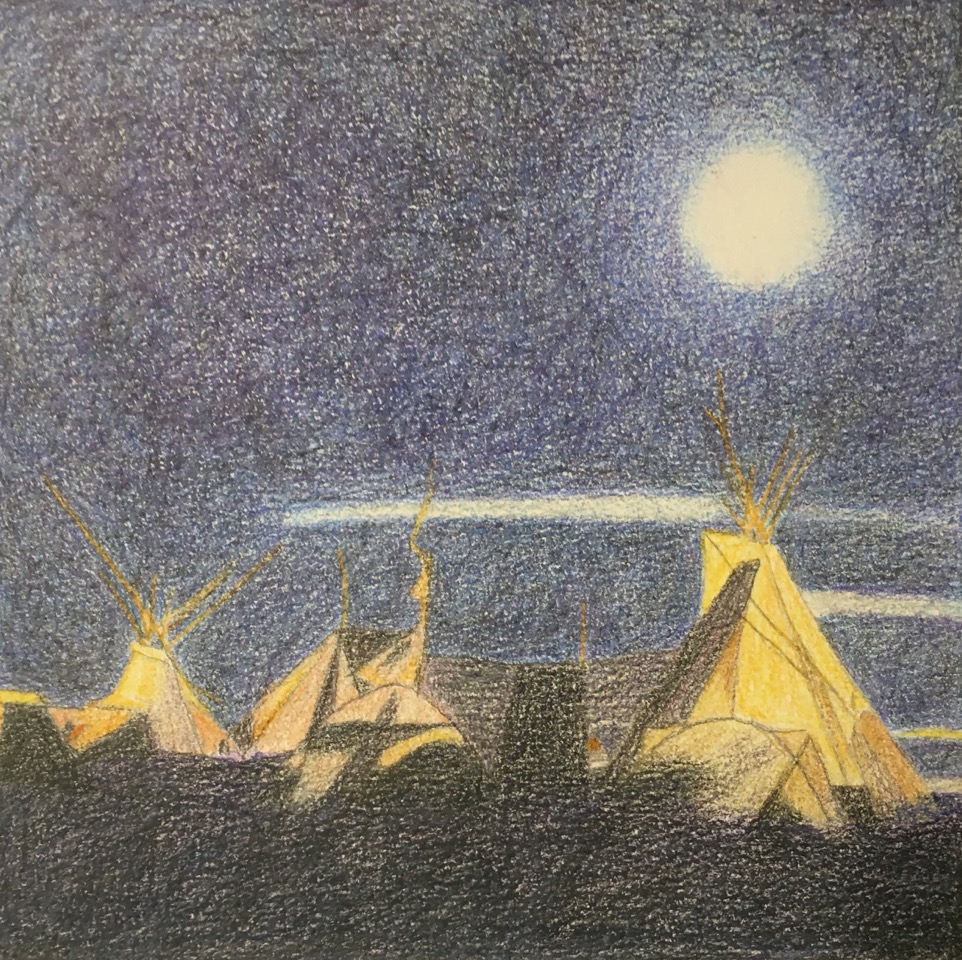

Original Artwork by Chip Romer: Each piece in the series is accompanied by original drawings by Chip Romer, the Executive Director of Credo High School in Rohnert Park, where Brendan currently teaches. In the fall, when Brendan shared with the administration that he planned to go to Standing Rock, he assumed that he would have to quit his job. Instead, they asked him to go as an ambassador for the school. The drawings are part of a series that Chip began while Brendan was at Standing Rock. They are a mediation, a reflection, and a prayer. The series is called, “Pictures of Resistance.” They are being shown publicly here for the first time, alongside Brendan’s writing.

Header image via Dark Sevier