By Chris Fink

It’s easy to mock Tucker Max’s What Women Want by opening to a page at random and reading a line or two, but I took it all in, deep. Unlike the hundreds of women who have apparently slept with the author, I hope I’m one of the only people who has read his whole book, because mocking is too gentle, like a teasing kiss, compared to the venereal bonfire this thing deserves.

To be fair, it is equally possible to open to a stray passage and nod along and be inspired. But they are almost all undone by lines like this: “women who value benevolent sexism more are happier with their lives.” There’s a lot going on here, but bottom line, the other editors at Little, Brown need to have a little sit-down with What Women Want’s editor, John Parsley.

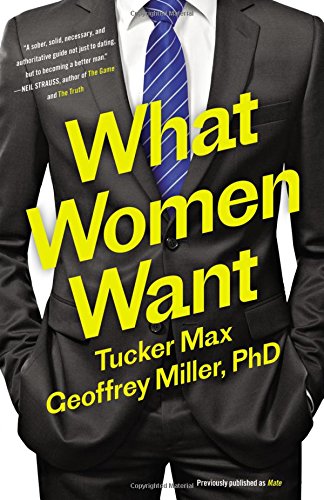

When taking this review assignment, I had no idea it was a self-help book. I didn’t know any more than its laughable title, What Women Want, which turns out to be a re-release and re-brand of a book called Mate: Become the Man Women Want, a more accurate but clearly too submissive title for its target audience. I’ll offer suggestions for even more fitting titles later.

The author’s name, Tucker Max, which I’d never heard of, only solidified my intention to eviscerate the book before opening it. But something happened when I was handed the paperback and saw Geoffrey Miller’s name on the cover as sub-author. It was a strange moment, like catching your father sleeping with your alcoholic volleyball coach. I adored a book by this accomplished evolutionary psychologist, The Mating Mind, a provocative and breezy presentation of Darwin’s most ignored contribution to evolution: sexual selection. The 19th century’s men-in-power went gangbusters twisting the other half of Darwin’s revolutionary theory, natural selection, to their ends, codifying the illusions of race, sexism, justifications of economic stratifications, and eugenics to their personal gain. Sexual selection, until recently, was laughed at as anything more than an afterthought subsumed by the mighty survival-of-the-fittest construct, as if rams smashing into each other was about who was more badass, not about impressing chicks. Ewe chicks.

But seeing Miller’s name on the cover of What Women Want, which I had yet to crack open at this point, made me think: Oh shit, was I too naïve when I read The Mating Mind? Is it a douchebag bible, like this book will probably be? So I waded in, without protection, with as open a mind as possible, leaving agenda and cynicism sidelined.

I headed out into public, where I do most of my reading, got some coffee, sat down, took the book out of my bag, then quickly returned home. I grabbed a copy of an old London Review of Books, ripped off the cover, and wrapped it around the image of a headless, medium-build, suit- and-tied man with his hands creepily in his pockets, and the big piss-yellow words WHAT WOMEN WANT sprayed across the cover. Then I headed back out.

The fundamental disaster is this: even if Miller is a little bit wrong about his sweeping hypotheses, his book is a dangerous manual for eugenics-lite at best, and a perfect guide for sociopaths at worst.

The layout for “The Five-Step Process to Mating Success” is as follows: Step One — “Get Your Head Straight”; Step Two — “Develop Attractive Traits”; Step Three — “Display Attractive Proofs”; Step Four — “Go Where the Women Are”; Step Five — “Take Action.”

How that doesn’t read like a WikiHow for serial killers, I’m not sure.

The book is constructed like an instruction manual for building an Ikea lady-snare out of your most basic instincts. A driving analogy is used adroitly early on, right at the opening of Chapter 1, titled “Build Self-Confidence”:

When you were 16 […] confidence […] low. At 26, however, your confidence is much higher because you’ve had 10 or more years of experience on the road without smashing into parked cars and running over children. When you get behind the wheel now, you understand all the unseen risks and thus have a very high expectation of getting where you intend to go safe and sound.

The entire rest of the book discusses how to become an excellent driver of a particular stripe, implying, by omission, that those who don’t will die off. It also ignores the fact, within this analogy, that horrible drivers are filled with confidence. On this proverbial road of life, how to know which kind of driver you are — let alone shedding delusion about said skill — is close to impossible, no matter how pithy or close to the “facts” of sexual selection the book is.

Women in the book are constant creatures of raw mate selection, at the whim of biological destiny, following rules you can rely on, presented with unconvincing science, though very confidently stated. If you’re a woman looking for yourself in there — unless you’re a sales/marketing Crossfit babe — then you’re not the girl for these authors. If you’re a heterosexual male not interested in those kinds of women, your chance of getting laid, let alone reproducing, is as potent as sperm in the wind.

Even aesthetic differentiation, which is only mentioned in two places and is insultingly reductionist, gets treated within the stalking-like confines of going after your lady-prey.

Of course, different women and different subcultures have different tastes. Goth women like black leather; hipster women like brown leather; kinky women like red leather. Laying down your own electronic music dance tracks in FL Studio software will impress more women in San Francisco than in San Antonio, and vice versa for playing Conway Twitty songs on the banjo.

It’s the Walmart approach to sex, where only the most mainstream hits within niches of desperate consumerism survive.

Paradox abounds in these pages. With what I think are sincere intentions, the book tries to be a good uncle to dumb-ass frat boys. Unfortunately, it offers them an American Dream-like promise that they can become better at scoring by making themselves better people — while also extolling a “science” that dictates whether you are born with those skills or not. If you have a mental illness or a physical weakness, or like Star Trek, give up, you’ll never be selected by a woman. There isn’t a single example of what someone with, for instance, a deformity, who has all the other sexual selection fitness indicators checked off, does to overcome the instincts of women who were born to, by instinct, uncheck his box.

There is one mention of gay men in this book and it is in what I’m assuming is full-Tucker voice, where he writes:

You are a young, relatively inexperienced gay man […] you and some friends decide to check out a new gay bar full of hot guys […] the guys are all as tall as NBA players, as muscular as NFL linebackers, and as sexually aggressive as a felon on his first night out of jail […] how would you feel in this situation?

One always appreciates attempts at empathy, metaphorical or otherwise, but it’s difficult to get past the slight logic spasm here: where men and women are supposed to have different brains but small gay men are “women” and big gay men are “men.” The sequence betrays the main flaw of this entire project: a total rejection of anyone who sits even adjacent to, let alone outside, binary gender roles. Sexual selection can accommodate homosexuality, vast individual variations, and sophisticated group behavior, but nothing anywhere near those constants in the biological landscape are mentioned. That same passage goes on:

Some of the male traits that frighten you most also seem to be the most attractive to you. The guys who pose the greatest physical threat are also the same guys you can envision making you feel safest. The guy who seems like the most egotistical player in the bar is also the one making you laugh so hard that your ribs hurt. It’s all a giant, swirling, pulsating contradiction. This is the world of sex and dating for women.

That sounds shockingly resonant to many women and is a rare insight for any male, but it’s also the equivalent of when a sitcom makes something feel real. It’s a familiar approximation, but still a cardboard version of life that relies on a view of reality that may not apply to all audiences.

The most sexist passage in Max’s treasure trove of misogyny may be surprising:

The Pill only arrived in 1960 — that’s just two generations of reliable female birth control. That’s not enough time for evolution to have recalibrated women’s mate preferences to this new reality that they could, in theory, have lots of casual short-term sex without getting pregnant.

Throughout the book, the authors are unequivocal about predicting female behavior, but here it’s a condescendingly generous “in theory.”

The book spends a lot of space assuring its reader of moral responsibility while extolling traits that are the absolute worst attributes of “men” who, if reading the book, can learn how to be more efficient at hiding their anything-but-empathetic intentions.

The hardest part of this review is that this toxic slog is somehow also full of good advice in the right context, environment, and dosage. For instance, in Chapter 9, under the header “Improve Your Agreeableness,” the bullet list contains: “learn to take care of animals, learn to take care of children, learn to mentor young people, learn to care for the sick, injured, and old.” That’s all beautiful, even if it’s in the service of chasing tail, but it’s one of too many roads that the authors ask their readers — whom they imply over and over are college-age at most — to traverse. The dedication is first “To our 17-year-old former selves.”

And there really are a handful of passages that would have made great Maxim short articles. The best science in the book is when, I assume Miller, lays out exactly why penis enlargement is completely impossible. And there are even sweet gems in there: “The best way to meet a lot of women is to make your dating life an extension of your social life,” a simple, healthy suggestion that works wonders for anyone who relies mostly on dating apps.

And just when I was ready to skim sections, which was almost always, I stumbled on beauties like:

Avoid the male-dominated business, computer, and professional development classes [when enrolling in continuing-education courses]. Focus on classes that attract young women, that involve fun interactions with other students, and that teach attractive skills — things like cooking, wine tasting, arts, crafts, music, dance, yoga, and psychology. These classes usually include a lot of middle-aged married women, but don’t ignore them — they usually have younger sisters, daughters, nieces, and coworkers that they’d love to introduce you to if you seem nice.

Miller offers this mea culpa at the start of The Mating Mind, which I think is why I forgave him his very loose speculations throughout that book:

There are also limits to my practical understanding of our mental adaptations. I know less about art than most artists, less about language than political speech writers, and less about comedy than Matt Groening, originator of The Simpsons.

What this short passage importantly reveals is that Geoffrey Miller lacks imagination. Of course, political speech writers are masters of language, but what about novelists, poets, translators? Matt Groening had almost nothing to do with why The Simpsons was satirical genius. Lack of creativity is a bummer for any scientist, but for an evolutionary psychologist, which is still dangerously close to being a school of the occult, it will rub up dangerously to the 19th century’s use of natural selection.

Sexual selection is real, genetics affect us in ways we’re not comfortable discussing yet, and conventional wisdom contradicts reality often, but we don’t know anywhere near enough about gene expression, epigenetics, diet, population flow, power dynamics, resource economics, associative mating, and a whole host of factors that directly affect how we interact to put so much confidence in Miller’s well-meaning mansplaining.

If this book was called What Women Wanted, discussed the speculations of how we evolved to pick mates, examined how we still struggle with those selection impulses, and researched how culture may be changing those impulses as a function of evolution, it could have been a real powerful work. As it is, in our current world, where the National Enquirer is the height of journalism, this book is a masterpiece of compassionate paternalism.

Suggested titles for a third rebranding: I Turned Forty and So Should You; Women Like Men Who Shower and Don’t Wear Crocs; Crossfit and the Fourth Reich; What Patriarchy?; You Might As Well Kill Yourself.

What Women Want will conjure memories of those old immortal Beatles lyrics: “And, in the end, the love you carefully plan and scheme is equal to the love you take from hopelessly instinctual lady creatures.”

Now get out there, and remember the closing chapter: “Create Your Mating Plan and Go Forth!”