Carmen Maria Machado begins her debut by asserting control. The first story in Her Body and Other Parties, “The Husband Stitch,” starts with a parenthetical guide to reading the story aloud. There are five instructions, but two stand out; the first is for the narrator’s father: “kind, booming; like your father; or the man you wish was your father.” The second is for “all other women,” for whom the reader is instructed to use a voice “interchangeable” with the one they use for the narrator. This dynamic largely shapes the book, as Machado and her narrators recognize and battle against the heteropatriarchal structures that have tried to shape their lives.

In that way, “The Husband Stitch” is a fitting title. It refers to an “extra stitch” doctors can add when sewing up an episiotomy after a woman delivers a baby so that her vagina is tighter, theoretically making sex more pleasurable for her husband. It’s a bodily transformation for no other purpose than pleasing someone else. In the story, after the narrator gives birth, her husband and the doctor make the decision for her without seeking her consent. One second they’re discussing it, the next she is out, and the next: “You’re all sewn up, don’t you worry,” the doctor says. “Nice and tight, everyone’s happy.” In a book full of passages that make the skin crawl, it’s one of the most disturbing.

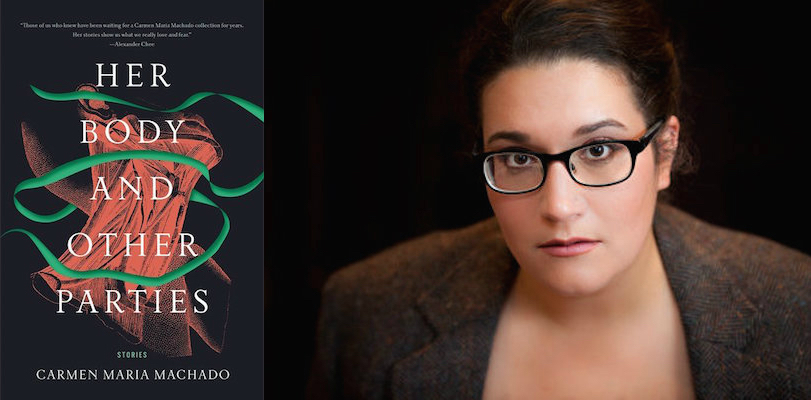

In Her Body and Other Parties, Machado draws the reader in with her formal experimentation and fantastical premise. While these methods are imaginative and surprising and effective, the weight of the book comes from her evocative portrayal of the banal atrocities that women (and queer women in particular) face every day. In the exploration of that subject, she finds herself in excellent company with other young writers like Jess Arndt and Kristen Arnett, while also carving out a space uniquely her own.

In “Real Women Have Bodies,” women begin mysteriously disappearing at the height of the recession. Nobody knows why, as the typical theories have been debunked:

At first everyone blamed the fashion industry, then the millennials, and, finally, the water. But the water’s been tested, the millennials aren’t the only ones going incorporeal, and it doesn’t do the fashion industry any good to have women fading away. You can’t put clothes on air. Not that they haven’t tried.

Machado efficiently draws the rules of her story’s world and efficiently criticizes those of ours. The vapidity with which the objects of blame seem to have been selected is frustrating in the face of such a bizarre epidemic. But it is no less vapid and should be no less frustrating in the face of more common events, where the blame still often falls upon millennials, despite being a generation with a tiny amount of power compared to the babyboomers that run the world, or a clearly gendered target like the fashion industry. The moment passes quickly, but Machado’s knife is sharp enough that it only takes one motion to make a deep cut. The mechanism by which the women are disappearing never becomes clear, though the narrator finds out that the women are not dead or gone but have “faded” and are incorporeal but still conscious and sentient. Without a how or why it can feel like there is no meaning in the loss outside of its phenomenology. In Machado’s hands, though, intrinsic meaning is unimportant because her characters make their own. “It turns out,” Petra, the narrator’s girlfriend says, “they think that the faded women are doing this sort of — I don’t know, I guess you’d call it terrorism…I like that.” Even when the women have lost their bodies, they’re still seizing control.

Machado also successfully reinterprets existing narratives, storylines and characters into something much more haunting in “Especially Heinous: 272 Views of Law & Order: SVU.” The story, organized in 272 short sections, each named after a Law & Order: SVU episode, follows the show’s Elliot Stabler and Olivia Benson as they do their jobs and traverse bizarre problems like mysterious sounds in the basement and shadow characters Abler and Henson. It’s a reclamation of a problematic property that commercializes sexual assault for the purpose of entertaining a massive audience. Machado, instead of focusing on the spectacle of their professional lives, zeroes in on the difficult consequences for their personal lives. She also deftly weaves a critique of the criminal justice system into the story. In the section “Cage,” she writes:

The rapist is raped. The raped are rapists. “Some days,” the prison doctor says to a resident as they stitch up another torn rectum, “I wonder if the bars make the monsters, and not the other way around.”

It’s a non sequitur (which the story is full of) that flexes the story’s focus, keeping its eyes on something larger than its immediate concerns. Machado is a juggler, and a talented one at that.

The real magic in Her Body and Other Parties is in the sentences. Few writers are as evocative and effective as Machado is, and there is no better example of that in the book than “The Resident,” which is nothing short of a small masterpiece. The story follows an emerging writer, identified as “Ms. M—-,” to a residency in the mountains at a spot called “Devil’s Throat.” It becomes ominous quickly when the narrator hits something with her car. “There, the black, lifeless eyes of a rabbit met mine. The lower half of her body was missing, as neatly as if she were a sheet of paper that had been ripped in two.” Machado’s command of metaphoric dissonance is prodigious, and this one never stops ringing. Things get no less spooky once she arrives at the residence. She’s told that they were not expecting her until tomorrow, though they’ll be ready for her that day. On the surface it is the type of bureaucratic inconvenience that happens all the time but in Machado’s hands the pleasantries born from this situation are social black holes. The characters navigate a your-fault-or-mine routine with precision, never allowing Ms. M—- to take the full responsibility she wishes to take for the mistake, or offering much in the way of sincere reassurance that her early arrival is not an inconvenience. The discomfort continues when another resident, without permission, goes to her car and retrieves her things for her. Once she gets to her room, she lies down for a nap and wakes up disoriented.

As I swung one leg from the bed, I had a monstrous vision of a hand darting from beneath the bed’s skirt, grasping my ankle, and dragging me beneath while the sound of delighted banter in the dining room drowned out my horrified screams, but it passed.

There is something writerly about the fear Ms. M— is expressing in that moment, emphasizing the irony of her would-be demise. Machado makes more out of the difficulty of writing than most, using the ups-and-downs of her work life as fodder a story that at times takes on the character of an intensely psychological horror-thriller. There are moments when the narrator’s body itself is the monster under the bed that prevents her from doing her work. Early on, she finds a bump on her thigh, which sends a “shock of pain” through her leg when pressed. She decides to puncture it and finds that “it resisted only briefly” and then “[a] limb of pus and blood climbed the stalk of the needle before […] trailing down my leg like an untended menstrual cycle.” The story persists with that type of event and imagery until its end, letting neither character nor reader out.

All good story collections are in some sense unified by a style or theme that binds the book together, but few cohere with as much force and energy as this book. Machado always keeps her eye on the ways women, particularly queer women, are fighting for bodily autonomy against a society that wishes to take it from them and the collective effect is towering. Her Body and Other Parties is an artful powerhouse and a writing textbook rolled into one. It is fearsome and fearless. It is a book that won’t be forgotten.