By Emily Wells

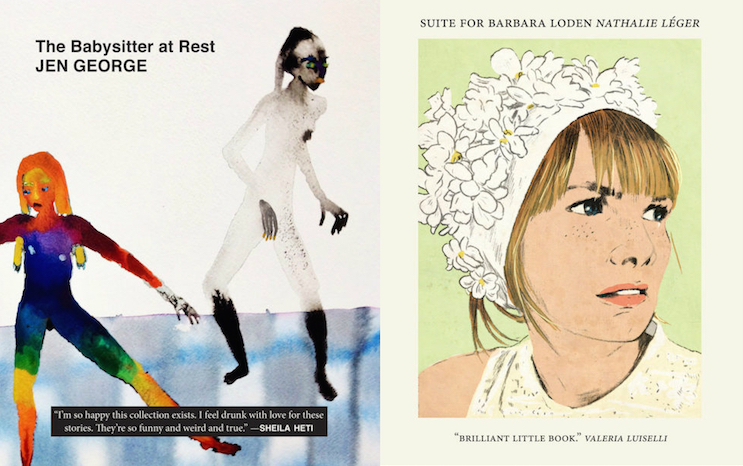

October was a thrilling month for Dorothy, a publishing project, a small press focused on publishing “fiction or near fiction or about fiction, mostly by women.” Dorothy releases their entire annual catalogue in October, in this year’s case, two small volumes: the first English translation of Suite for Barbara Loden by Nathalie Léger, and a collection of short fiction, The Babysitter at Rest by Jen George. The two books compliment each other well. Both are unconventional forays into the burdens of womanhood and storytelling, and are desperately concerned with what it means to be female and unfulfilled.

¤

Nathalie Léger’s Suite for Barbara Loden covers an astonishing amount of ground. At once, it is fiction, biography, history, and the journey of all-consuming research. It begins with a Sebald-esque quest, in which the protagonist (an extension of Léger) embarks to find out everything she can about Barbara Loden, the writer and director of the 1970 film Wanda. The film follows a generally passive woman (played by Loden) as she leaves her husband and children, begs a neighbor for money, gets picked up at a bar then abandons the man the following day at a rest stop. Later, she becomes infatuated with a man she believes to be a bartender, who is actually a bank robber.

It is fitting that Loden is the object of Léger’s fascination, given the inclination of both women to make art that blurs the lines between themselves and their work — “It’s like showing myself in a way that I was,” Loden said in a 1971 interview about Wanda. The film is a favorite of John Waters, Isabelle Huppert, and Marguerite Duras. The frequent comparison between this book and the work of Duras is an apt one. The North China Lover (another version of The Lover, in which Duras added notes for how she would have liked the film to have been made) especially comes to mind. Both books contain vastness in a slim volume.

Given the nature of the book, Léger spends a great deal of the pages describing her process, including how she initially became so captivated with Loden when she was asked to do a short entry for a film encyclopedia:

“Convinced that in order to keep it short you had to know a great deal, I immersed myself in the history of the United States, read through the history of the self-portrait from antiquity to modern times, digressing to take in some sociological research about women from the 1950’s and 1960’s […] I felt like I was managing a huge building site, from which I was going to excavate a miniature model of modernity, reduced to its simplest, most complex form: a woman telling her own story through that of another woman.”

This spirit, of women telling their own stories and those of other women, is present throughout the entire work. Suite for Barbara Loden, is above all, a story of Léger’s obsession against the impossibility of the task of piecing together the life of a woman who invented a character as close as possible to herself. Leger switches between artfully describing the scenes of the film and sharing the details of Loden’s biography, inner life, and influences that she is able to discover:

“When Barbara Loden was asked why she played the part herself (wouldn’t it have been easier for her first film to work with another actress playing the part of Wanda? Wouldn’t it have been simpler for her first film to concentrate on directing rather than having to negotiate the exhausting back and forth from one side of the camera to the other, the orders to give, the decisions to make, the permanent worry?), Barbara would answer almost contritely, as if she were apologizing, that only she could do it. ‘I was the best fit for it.’”

Of course, it is the power of literature that allows Leger to accomplish her goal in the end. She explains that she could not possibly gain access to the papers and documents that would have allowed her to retrace the life of Loden to her satisfaction, and that in the end, it is the fictionalization of Loden’s life that allows her to experience some of the closeness she desires. She seizes more agency in telling the story with the encouragement of a documentary filmmaker: “he said to me — this man, who never works on anything that isn’t real, said to me quite calmly — ‘Make it up. All you have to do is make it up.’” The story is Leger’s after all, and she struggles to understand why she was drawn to Loden and Wanda in the first place. What is initially Léger’s explicit hesitance to create a biography that does not do Loden justice is transformed into her own story, one of how the lives of women seep into one another. One facet of Léger’s fascination is the concern for what women end up consenting to in the pursuit of love:

“I’ve allowed myself to be pushed around, just waiting for it to be over, preferring misunderstanding over confrontation — it’s impossible in moments like that to think that defending my body could be worth the effort, and anyway what does that mean, “my body,” at the age of fifteen? Only this matters: not to be alone, not to be abandoned.”

Speaking of her husband Elia Kazan, Loden once said to a magazine: “He taught me that what mattered most was not to remain silent. Before I never said a word, I was always silent. And now, what’s left for me to do? He told me you’ve got to be heard. Everything that you do must be heard. That’s why I made Wanda. As a way of confirming my own existence.” While the woman to whom Léger has given a voice is certainly a fabrication, she is a vibrant one — a woman that confirms the existence of herself, Loden, and other women. The book is an accomplishment especially in exploring the nature of the fused identities of women and the female artists they are drawn to.

Supplément à la vie de Barbara Loden, the text in its original French, was released in French in 2012. An excerpt, translated to English, was published in the Paris Review in 2016. The Dorothy release is the first fully-translated edition of the book. Léger’s work is impressively diverse, as she also translates, edits, and curates, including exhibitions on both Beckett and Barthes at the Pompidou.

¤

The five stories in Jen George’s The Babysitter at Rest depict a world in which the female protagonists are not only willing to debase themselves; rather, it is an assumed part of their existence — of which they are painfully self-aware. The hilarious and heartbreaking stories are long, some the length of novellas, and full of sardonic observations on the futility of what is generally considered maturity or success or love. George captures the loneliness that comes from participating in a society that feels rigged against sadness, intimacy, and genuine expression.

The collection’s first story, “Guidance/The Party,” follows a 33-year-old protagonist who is instructed by a genderless, tequila-chugging guide, set on steering her toward adulthood. The Guide breaks into her home to offer dubious, unsolicited advice, throws her journals in the trash for the sake of her “future sense of self-worth” and says she “must now claim to enjoy things, learn a lot, and know yourself — this will heavily influence others’ assessment of your objective beauty and worth. Be aware that too much proselytizing may date you, so don’t go overboard. Your life may fall apart around you while you’re putting on the act of radiating positivity, but you will not realize it for some time.” The Guide throws away her unflattering clothes and forces her to have a party so she can show herself off as the embodiment of empowerment and accomplishment. Of course, this doesn’t entirely work out, and the woman is left contemplating missed opportunities and her long-term dissatisfaction:

“Q: Was there a particular point at which I should have done something different: gone to school for something specific, made professional advances, interned, taken a risk or leap of faith, asked for help, called people back, shown gratitude, applied for a job with a salary and benefits, saved money, gotten insurance, built a community, resigned myself to a relationship with someone for financial stability, had a baby?

A: Probably.”

Lost opportunity remains one of the main concerns in the book’s title story, which is perhaps the gem of the collection. The story opens:

“I’ve been given a fresh start, a new beginning. It’s almost like being reborn, but without birth and childhood. I get to start as a young adult, when you are capable of looking after yourself and making decisions. When your body is in its prime. The only rules are you start pretty broke, and you have to have roommates.”

Then the underage (or at least likely-underage — she doesn’t remember exactly how old she is) protagonist has an inappropriate affair with the father of a baby that she is paid to babysit. The baby will never grow up, and the babysitter often reminds him that she is not his mother, that she is paid to watch him. The baby’s father asks her not to “pursue obscure aspirations of becoming something, though I know you wouldn’t know how to even if you wanted. It’d spoil you. You are better the way you are.” And in this way, her sense of fresh start and new beginning are negated. The presence of authority figures is pronounced throughout the stories — doctors, teachers, domineering lovers, and Guides obliterate the wills of the female protagonists and replace it with their own.

In “Futures in Child Rearing,” the protagonist struggles to name a hypothetical future child because of her certainty that each name will result in a very particular life. She wants to name the child Ocean, but fears the implications: “the void, the vast emptiness, the unknown, big whale shits, giant octopuses, or other possible tentacle situations.” She also considers Meriwether, Jupiter, You Have Reached Your Destination, Horace, Atta Girl, and You’re OK:

“You’re OK is a good name because I always liked when people said that to me. There is reassurance in that name. She’d reassure herself and others in instances of injury such as falling down the stairs, getting hit in the head by a soccer ball traveling at high speed, slipping on ice and hitting the tailbone so hard she would like to cry but doesn’t, or being knocked down by a rogue wave while wading in the ocean. On the other hand, there may be an element of mediocrity associated with the name, because of the ‘OK,’ that I’m unwilling to accept.”

In “Instruction,” the final story in the collection, the protagonist writes a song called A Woman Trying to Believe in the Inherent Benevolence of the Universe that She’s Read About in Self-Help Books and Spiritual Manuals. This could have been an apt alternative title for The Babysitter at Rest, and captures George’s ability to dignify the pathetic with an air of tragedy.

Deadpan, dark, and acerbic, George’s collection is sure to delight those with a penchant for dark humor and eccentric articulation of distress.