Working for an NGO is a little bit like running for elected office: no matter what high-minded goals you hoped to achieve, nor what level of idealism got you involved in the first place, you generally spend most of your time raising money. Crisis breeds opportunity; visibility equals funding. Donations to charitable organizations vary with the news cycle. To not have your name associated with a humanitarian event that is getting daily play on television is practically the equivalent of malfeasance.

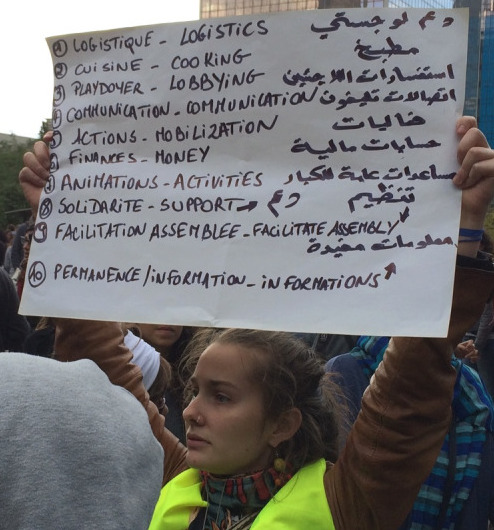

The first turf battle to play out in the refugee camp in the center of Brussels came after only a few days, when SAMU Social, the social services organization that has been working with homeless, addicted and otherwise marginalized people in Brussels day in and day out for the past fifteen years, attempted to take over the operation of the camp from the Citizens Platform for the Support of Refugees, a group of ordinary citizens who had organized on Facebook and were by all measures doing a remarkable job of looking after the needs of the refugees in the park. Accounts of what actually happened on that Monday afternoon a few weeks ago vary. Some say there was merely a heated exchange between the two groups over who was running the show, others that there was nearly a fistfight. It was short lived, however, and today the two groups are working together in a cordial, if occasionally tense, relationship. They get along well enough that some of the Platform volunteers even work occasional shifts in the SAMU tent. It was a different story when Oxfam showed up a week in with, as one volunteer put it, “a few boxes of clothes and wanted to put up this huge sign at the front of the camp.” (Long story short: they didn’t.)

But such divisions among the organizations on site are minor when compared with the political faults this crisis has opened, both within Belgium and across Europe. Like tremors lighting up a seismograph, the refugee influx highlights and exacerbates fault lines that already exist.

Attempting to fully understand Belgian politics is a quagmire for the foolhardy, but suffice to say that the country is divided into a Dutch-speaking north (Flanders) and a French speaking south (Wallonia), and that the two populations don’t much like each other. The Platform volunteers in the park are overwhelmingly French-speaking. The Secretary of State responsible for asylum seekers and refugees belongs to a conservative Flemish separatist party (the New Flemish Alliance, or N-VA).

(Although the term “conservative” here is relative. One measure of how far to the right the United States is compared to Belgium, and much of Europe, is that one of the debates over immigration here currently revolves not around whether to give full citizenship status to people granted asylum, but whether to do so after four years of residency, as the N-VA proposes, or immediately, as the French Socialists want.)

The fireworks began pretty quickly. During the first week of the camp’s existence Belgium’s Deputy Prime Minister, who is Flemish, demanded that the mayor of Brussels, who is a French speaking socialist, clear the refugees out of the park immediately. The mayor replied, grandiosely, since it’s not what had been proposed, that he would never send in troops against the “people of the park.” The mayor of Antwerp, who is also the president of the N-VA, called the mayor of Brussels “totally incompetent,” to have let the camp develop in the first place, and said that the reason the park was not being cleared was that it had become a “hot bed of extreme left activists”. The mayor of Brussels responded that the entire crisis has been created because the federal government has not done its job, i.e. allowing only two hundred and fifty asylum seekers to register each day, and failing to provide sufficient shelter for the rest.

Political pyrotechnics aside, it has been pretty obvious from the beginning that Belgium, like all of Europe, has two options in response to this crisis: increase its capacity to take in refugees and process asylum claims or slough off numbers of refugees, whether by shipping them to other, more receptive EU countries or back to wherever they came from. They appear to be doing both. Belgium recently announced that it would grant asylum to a little more than four thousand asylum seekers in the coming year. But with anywhere from forty to fifty thousand migrants in the country, this represents an acceptance rate of less than ten percent, the remainder being shipped back to their countries of origin. Also, it was announced last week that accommodation for eight thousand migrants will be added to the 28 thousand already created since the summer, these to house refugees between the time they register their asylum claim and the time their petition is formally adjudicated, which can be anywhere from three months to a year. Generally, these people are housed in camps run by the Red Cross, often located near airports, presumably to enable speedy deportations once asylum status has been denied.

The federal government is making concerted moves to clear the park, not with the stick of sending in troops, but with the carrot of providing facilities superior to camping in tents, like showers, food and warmth. Now that the weather is setting in, more and more refugees are packing their hand-me-down belongings into donated blue Ikea bags and moving indoors. In addition to being better, in the long term, for the refugees themselves (a point even the Platform volunteers acknowledge) the move inside will benefit the Center-Right coalition government by denying the park as a rallying point for “radical leftists,” as the mayor of Antwerp recently put it, and making the refugee situation less public. The scale of the migration caught the politicians off guard, but they are beginning to recover.

Across Europe the divisions are starker. Turkey has built a series of state-of-the-art refugee camps along its border with Syria, featuring three-room units for each family, with electricity and running water and a fully stocked supermarket where the residents (they are more residents than refugees, there) shop with debit cards funded monthly by the Turkish government. But these camps are only for Syrians. The Iraqis in Brussels talk about the level of discrimination they faced in Turkey, where they are payed below-market wages and kicked out of apartments the moment higher-paying tenants are found.

In Greece, many citizens go out of their way to help refugees who make it ashore after the human-trafficker roulette of the sea crossing, tacitly ignoring a recently passed law making it illegal to aid migrants. But in Greece, no political party has benefitted from the influx of foreigners so much as Golden Dawn, a party whose official symbol is a repurposed swastika.

Immediately to the north of Greece, Macedonia seems to be aware that all the refugees want to do is cross it, and seems to be facilitating that procession as rapidly as possible. Hungary probably understands that transit is all that is being sought from it, too, but has a grandstanding president who seems determined to make examples. (Many refugees in the camp in Brussels say that the people of Hungary are actually pretty nice. It’s only the government and the military and the border police and the roving bands of criminals who stalk the forests mugging those who have money and beating those who don’t who are mean.)

Serbia, too, seems to understand that it is simply an area of land to be traversed, but just can’t seem to help itself, and is impishly sending refugees the long way round, via its old adversary Croatia, as though playing a game of human hot potato. “We are like water,” said one refugee on the Serbian border with Hungary, “when we encounter a rock, we flow around it.”

Croatia, for its part, briefly stuck its head up over the dike last week and opened its border like a spillway, allowing migrants to pass unchecked around Hungary. But just as quickly, it realized the flow was a tsunami, and ducked back behind a dam of border controls.

Austria, for those refugees fortunate enough to make it there, is acting as a distribution center, the O’Hare Airport of this hub-and-spoke network, taking in and then sending on thousands of asylum seekers to France, Belgium, The Netherlands, and especially Germany. Germany. It’s where everyone wants to go who hasn’t wound up somewhere else. Germany recently announced that it would process eight hundred thousand asylum applications this year alone, and would take in up to half a million asylum seekers each year for the next five years. Germany, they all say. They want to go to Germany.

Germany is exorcizing its demons.

The refugees in the park seem to be excruciatingly aware of the geopolitics. Apparently the first group of them, the occupants of those fifteen lonely tents pitched in the park the beginning of September, wound up in Brussels purely by chance, their traffickers liking the odds here better, or blocked off from some other, preferred route, or simply running low on fuel and paranoid. Then that first group of arrivals radioed back down the line, FaceBooking and emailing and Twittering the under-ways and the yet-to-embarks that they were being received amicably, and the faucet was opened. But now they closely monitor the news, weigh options, plan contingencies.

But how great is the flow? It’s the question posed incessantly by the conservatives, the xenophobes, and the Prime Minister of Hungary. Will we not soon be inundated? The Muslim population of Europe now stands at about four percent of the total population. If Europe were to accept every single refugee currently seeking asylum on the continent, the total Muslim population of Europe would rise to about five percent. On such fine political and demographic calculations hinge, apparently, the political future of the European Union.