David L. Ulin writes: California owes its name to the written word. The source is the fictional Queen Califia, whose story comes from the Spanish writer Garci Rodríguez de Montalvo’s 1510 romance The Adventures of Esplandián. “Know ye,” Rodríguez de Montalvo wrote, “that at the right hand of the Indies there is an island called California, very close to that part of the Terrestrial Paradise, which was inhabited by black women without a single man among them, and they lived in the manner of Amazons. They were robust of body with strong passionate hearts and great virtue. The island itself is one of the wildest in the world on account of the bold and craggy rocks.” Is it any wonder, then, that when Diego de Becerra and Fortún Ximénez landed at the southern tip of Baja in 1533, they chose to name the place the Island of California, as if they had discovered their own heaven on earth?

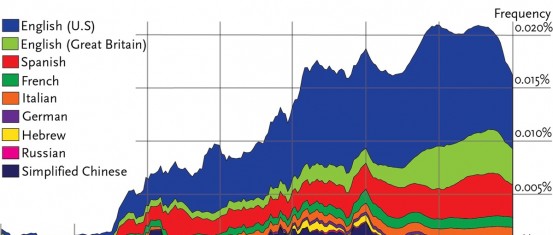

I think about the Island of California when I look at Joshua Comer’s data analysis graph. His task — to track the word “California” (and related phrases) through millions of books published across nine languages and several centuries — appears simple enough, but what it yields is something else again. To me, it looks like a voiceprint, or a series of overlapping voiceprints, the residue of a conversation we’ve been having without ever really calculating it, from continent to continent and year to year. It may start with Rodríguez de Montalvo, but it’s the proliferation that’s important. . . or, better yet, the cacophony.

Cacophony? Yes, the cacophony of California, which is itself made up of voiceprints, languages interrupting one another, each reading (and writing and speaking) the place through its own filter, its own point-of-view. Such an idea comes embedded in the very heart of Comer’s research, which seems to address the state as both myth and landscape, manifest and historical destiny, demographic and promised land. I’m not even going to try to summarize his findings; to be honest, I don’t think I could do them justice, and anyway, I’m less interested in the data than in the effect. Still, for all that his graphs reveal the fate of references to the state and some of its most essential tropes (the “California dream,” for instance, or “Californian gold”), what they also do is suggest that this is just the beginning of the story, that we are looking at the expression of California as idea.

Read the full piece, and look at Comer’s graphs, here.

(Have you heard? Boom: A Journal of California has joined LARB’s new Channels Project. The LARB Channels — which include the websites Avidly, Marginalia along with Boom — are a community of independent online magazines specializing in literary criticism, politics, science and culture, supported by the Los Angeles Review of Books.)