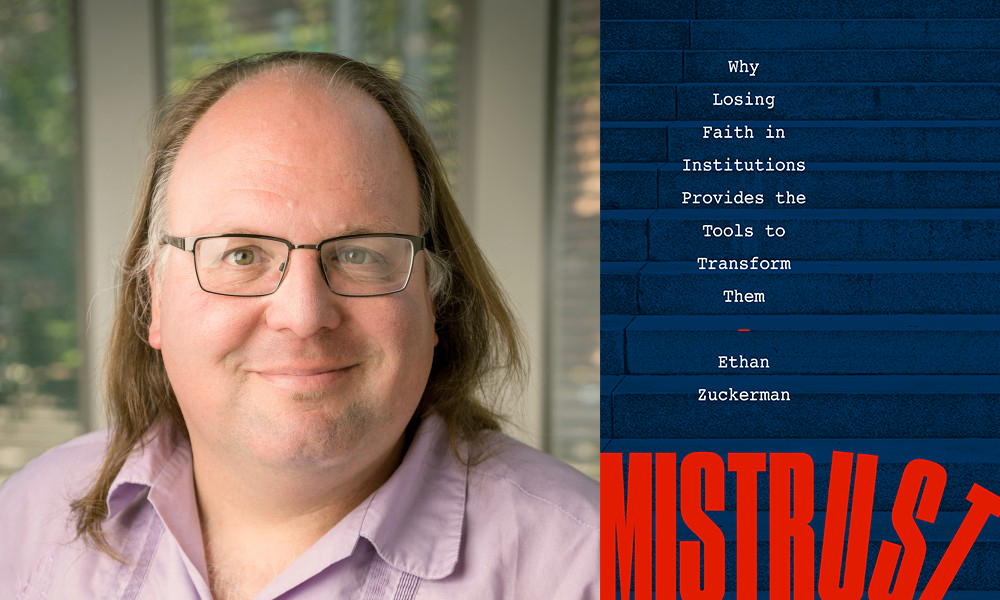

How might digital-media activists and innovators push beyond simply critiquing data-surveilling corporate platforms? How might they build their own public utilities? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Ethan Zuckerman. This present conversation focuses on Zuckerman’s recent essay “The Case for Digital Public Infrastructure.” For the last decade, Zuckerman has directed the Center for Civic Media at MIT. Zuckerman soon will launch the Institute for Digital Public Infrastructure at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. His research focuses on the use of media as a tool for social change, the role of technology in international development, and the adoption of new technologies by activists. He is the author of Rewire: Digital Cosmopolitans in the Age of Connection. With Rebecca MacKinnon, Zuckerman co-founded the international blogging community Global Voices — showcasing news and opinions from citizen media in more than 150 nations and 30 languages. In 2000, Zuckerman founded Geekcorps, a volunteer organization that sends information-technology specialists to work on projects in developing nations, with a focus on West Africa. Previously, he helped found Tripod.com, one of the Web’s first “personal publishing” sites. Zuckerman blogs here. W.W. Norton will publish his new book, Mistrust: Why Losing Faith in Institutions Provides the Tools to Transform Them, later this year.

¤

ANDY FITCH: To start from your basic point that tech innovators’ business models don’t emerge inevitably or consistently across the world, but instead get shaped by distinct societies making their own political and economic choices, could we first compare a couple of historical trajectories for broadcast media? Could you describe how British public-service broadcasting’s emergence in the early 20th century established certain international parameters (in terms of societal function, and funding models) for radio and then television? And how did US approaches depart from this British model — first through more decentralization and commercialization?

ETHAN ZUCKERMAN: Let’s start with the rise of radio. Radio emerges incredibly quickly. The first consistent radio broadcast of voice and music doesn’t get launched until 1912. But then, within 10 years (so by 1922), we see reasonably mature models for radio broadcasting. Radio develops independently in a bunch of different places. Several people have a claim to the basic technology, primarily the tube amplifier. This three-element tube, the transistor’s basic antecedent, allows you to broadcast and to receive actual waves of sound over radio. Until that point, we could only transmit bursts of static. Though then when the tube amplifier appears, all this radio gear produced for World War I (to send Morse code back and forth), now being resold to hobbyists, suddenly becomes useful for broadcasting over very large distances. So everybody now has to figure out: how will radio work? What will it offer?

The US predictably embraces a form of creative chaos. Everybody and their neighbor tries out radio. High schools and colleges and universities start radio stations. Churches broadcast sermons via the radio. Department stores get in the game, because of course they want to sell radio sets and radio receivers. And for maybe my favorite example, hotels, many of which already have ballroom orchestras, start their own radio stations — again as a way of creating content and sort of advertising at the same time.

Soon the US has more than 700 stations on air, offering a diverse mix of commercial and non-commercial content. The commercial model still hasn’t been fully worked out, until American Telephone & Telegraph (AT&T) realizes its long-distance phone lines provide this great way to get voices to radio stations. The first radio ads appear when a Long Island real-estate salesman purchases 10 minutes of air time to pitch his new housing development. That causes a lot of controversy, with people questioning whether direct advertising into the home is appropriate. But over time this model gets further established.

Through a combination of these various innovations and of FCC decisions (giving more weight to commercial than to nonprofit stations), radio in the US gets consolidated pretty quickly around this model combining local broadcasters and some nationally syndicated programming — sent over telephone wires, and supported by advertising. So within another decade (now by 1932), US radio has emerged out of chaos into this more or less free-market model recognizable to us today.

Britain does something radically different. Britain has a similar number of radio innovators — sometimes even the same people. The American Marconi Company quickly becomes a big deal in the US. But Marconi himself lives in Britain. He starts up various radio experiments, as do a number of people. Though then, most basically, the British Post Office jumps in and says: “Nope. This won’t do. We can’t have that kind of chaos they have in the US. We need a single broadcaster. We need to control the airwaves, and decide on what’s fit to put out there.”

So the British government recruits John Reith — a minister’s son, and an engineer. When Reith takes the job, he doesn’t really know what radio is. But he ends up filling this new role quite well. He has a very strong moral sense. He has a strong sense of propriety. And rather than that leading to some stultifying agenda (which certainly could have happened), Reith’s principled approach leads to the BBC emerging as this quite new phenomenon, the public-service broadcaster. This all becomes especially clear about two years into the BBC’s existence, during a nationwide strike. The newspapers have gone on strike. Radio suddenly becomes the main news source. Until this point, the BBC has pretty much steered clear of news reporting, with the newspapers terrified that radio will put them out of business.

During this 1926 strike, Reith and his staff start finding ways to put on air not just government officials, but labor leaders. That introduces this quite revolutionary approach to public broadcasting, where you’ll hear directly not just from information ministers, but from opposition forces as well. That transformative approach ends up astounding British audiences, and starts to define the parameters of the BBC’s public mission. The BBC’s public-service broadcasting will differ from government-controlled media, and also from the explicitly commercial proposition coming out of US radio.

Both countries already have newspapers operating as incredibly powerful commercial entities. At first, radio seems likely to offer the same. But the BBC soon develops some distinct advantages over US broadcasters. It has a monopoly. It has this incredible revenue stream, from annual license fees that the Post Office levies on radio receivers. So it has a fantastic budget, and all sorts of benefits that the US system doesn’t directly provide to broadcasters — though the US system still does quite well for itself.

Could you likewise sketch those British and US models starting to converge later in the century, say through a Great Society-era Corporation for Public Broadcasting seeking to complement profit-oriented media?

Not until the 1960s does the US take a closer look and start thinking about something like public broadcasting. Newt Minow emerges as a central figure. When JFK gets elected, Minow, a Democratic activist close to Robert Kennedy, becomes FCC commissioner. Minow then terrifies the broadcast industry, by calling television a “vast wasteland.” They think he plans to put them all out of business. For one wonderful little detail, from Gilligan’s Island actually, the ship which runs aground, stranding everybody on the island, has the name the S.S. Minnow.

But Minow ends up doing something quite different from what commercial broadcasters had feared. Rather than try to ban anything, or take it off the air, Minow basically approaches possibilities for public broadcasting from the perspective of market failure. “Look,” he says, “we’ve failed to provide good children’s programming. We’ve failed to provide good local news.” So Minow starts putting in place the infrastructures that will bring us PBS and NPR. The FCC starts funding the Corporation for Public Broadcasting. This new US approach basically says: “Maybe we don’t need or want an exclusive system like the British have. Maybe public media can add to our existing broadcast system.”

Of course Britain itself hits a point when they start to open up their own airwaves to broadcast competition. They still have the license fee. Radio and television audiences still pay for the BBC. But competition emerges both from satellites and from commercial broadcasters. So eventually, those two distinct national approaches do start to converge.

Then for a quick comparison between two 21st-century techno-media models, could you sketch what makes China’s digital ecosystem particularly rich and complex today: much livelier than a preceding generation’s authoritarian state culture, much more innovative than many American commentators suggest, much more immersive than social-media platforms’ hold on US users, all leading to hypermonopolies that Silicon Valley CEOs “can only dream of” (as well as to terrifying prospects from the perspective of civil-liberties, privacy, and antitrust advocates)?

First, as you suggested, we shouldn’t think of China’s digital sphere just as authoritarian and state-controlled. Americans dismiss China’s model of digital culture at their own peril. Here I sometimes think back to when President Clinton, discussing the Chinese state’s relationship to the Internet, said China would find it impossible to censor the Internet, which he likened to nailing Jell-O to the wall. Well, Chinese Jell-O-nailing technology has in fact gotten pretty good. But even with the Chinese internet closely controlled and often censored, it’s still enormously vibrant.

We have to factor in, for example, that Chinese mobile-phone culture already has moved leaps and bounds beyond typical phone usage in the States. Almost no one in China carries cash. Everybody does payments on their phones. And Chinese social-media platforms rarely operate as stand-alone companies. You don’t just have some Chinese equivalent to Facebook, which lets you talk to your friends amid a bunch of advertising. Instead, these extremely large and complex companies often provide their own vertically integrated ecosystems.

So if use Weibo, that’s Sina Weibo, which also includes all Sina.com services: from search, to microblogging, to taxi service, and pizza-delivery service, and online shopping services. They all get bundled and integrated within this single Sina system. Whether you use Weibo or Weixin or something similar, that system can move quite seamlessly between conversation and transaction and navigation of the real world. And yes, the Chinese state does have some control over all of this. Yes, specific types of speech almost certainly will get taken down. But that all happens within what still remains this amazingly vital and creative space.

So when my essay refers to forms of vertical integration that Silicon Valley CEOs can only dream of, I have in mind, say, Facebook really wanting its own cryptocurrency. Okay fine, but that will just mean catching up with Chinese companies which built payment systems into their technology from very early on. Or when you see Uber trying to figure out how to do everything (how to spread beyond ride-hailing to Uber Eats, for example), I think of that as a very Chinese way of doing digital services.

Then alongside these cases of US monopolistic and Chinese hypermonopolistic platform concentration, you present Wikipedia as a high-profile, highly trafficked digital enterprise structured by well-articulated values and goals — less subject to market signals, deliberately abstaining from advertiser-based revenue, or surveillance of users. You suggest that Wikipedia’s reputable and efficient volunteer contributions make a lean firm like Facebook look administratively bloated by comparison. You also describe various intriguing Wikimedia spinoff projects, while acknowledging a lack of such striking successes outside the encyclopedia domain. So what further possible horizons might this Wikipedia model point towards, particularly if innovative platform designers commit to building outside the logic of commercial markets and “practical” operational plans (narrowly premised on sustaining themselves through data extraction or ad/subscription revenues)?

We can easily overlook Wikimedia’s remarkable successes, particularly in the encyclopedia space. If you remember, 10 years back, we had a debate much more about whether you could rely on anything from Wikipedia. After all, anyone might have written it. In certain infamous cases, someone would have vandalized somebody else’s biography, or added something scandalous which then never got corrected. But a decade later, we have fairly widespread acceptance that Wikipedia mostly gets it right most of the time. So when YouTube, for example, decided to do some fact-checking and add neutral verifiable information to video posts on controversial subjects, they leaned on Wikipedia.

In a funny way Wikipedia has transformed into basically our best attempt at a shared conceptual reality. So could this Wikipedia model work for anything else? Well first, we should acknowledge that this Wikipedia model still doesn’t work perfectly even around its essential encyclopedic content. Any number of people involved will tell you that this notoriously prickly community still shows systemic biases against articles on women, against articles coming from Africa or other developing regions. And then, in terms of Wikimedia’s ongoing limitations, we have the fact that it really hasn’t yet figured out how to reinvent anything other than the encyclopedia.

Wikidata does offer a different type of encyclopedic database, accessible for other kinds of research. But Wikimedia has not fully succeeded in reinventing the newspaper, for instance, or establishing new forms of open-source publishing. Perhaps more fundamentally, though, they’ve offered the world this really helpful scaffold. They’ve basically said: “Hey, here’s how we’ll interact. We’ll ask people to write encyclopedia articles. And not only do you already know what an encyclopedia article looks like. You probably can imagine how you might add to an existing article. So our articles can start out a little stripped-down, but then people can figure out ways to expand on them.” That template, that script, sort of cracked the code for successfully letting people participate, and for encouraging them to participate in productive ways.

Here you could even think of something like TikTok — this Chinese network essentially trying to get everyone to produce music videos. TikTok also provides its own basic script, along the lines of: “Hey, remix this. Hey, participate in this craze.” Of course Wikipedia might provide a greater social benefit than that. But in both cases, the question now becomes: what else can these volunteer models build? A couple years back, for instance, Wikimedia tried to build a search engine — not designed to compete with Google, so much as to compete with something like WolframAlpha. It was more of a fact engine, and also made a broader case along the lines of: “Look, Google increasingly relies on Wikipedia to make search work. YouTube, of course, is itself a Google company. But our Wikipedia brand keeps getting overshadowed in the process. So rather than just get subsumed into Google fact boxes, or answers from Siri or Alexa or something, maybe we need to put ourselves forward as Wikimedia.”

But the community soon backed off of that. They seemed to decide it was just too ambitious and too wild. But I still consider figuring out how to run WikiSearch a very worthwhile project. I’ve started talking to some libraries about related models, for certain frequently researched topics. How do you stay safe from COVID-19? How does the electoral college work? Particularly for evergreen topics that always will get searched a lot, and that likely will remain somewhat controversial, what would it look like to design a Wikipedia-style search-results page, and with this appearing on the front end of a Google search — rather than just Google’s algorithm-generated results? To me, that sounds like a very healthy innovation.

Still Wikimedia has pulled off a very successful model, driven by high-quality volunteers and a devoted user base who donate to it. Could other sites manage this combination as well? Hard to say — which points to why, ideally, we wouldn’t just rely on philanthropy, but also on public funding.

And even the most forceful critiques of Big Tech platforms might at times, you suggest, further cement these platforms’ ongoing centrality — rather than providing real-world alternatives. So instead of just playing defense by denouncing data-surveilling practices, could you sketch some additional ways to play offense today, for instance by combining “the ambition and comprehensive vision of the early BBC and the ability to complement commercial media exemplified by PBS and NPR”? Could you point to how the Corporation for Public Broadcasting’s historical emergence, for example (again, long after certain media forms had established significant commercial clout), shows us that it’s still not too late to offer this kind of intervention in present-day media ecologies?

Here instead of the Corporation for Public Broadcasting, I’d actually focus on the Children’s Television Workshop. CTW comes about in the late 1960s, really to address the question of whether we can provide universal preschool, perhaps by using television. They do an enormous amount of research, over three full years, with childhood-education specialists, with preschool and kindergarten teachers, with writers, directors, puppeteers. From that research, they come up with Sesame Street, a pretty magnificent fulfilment of this goal of creating televised preschool — and also a powerful demonstration that, like you said, we always can come in and fill some of these gaps left by our siloed commercial media. So when I look at that precedent, I wonder how we might create and fund dozens, perhaps hundreds, of projects that take on those gaps in some similar way today. How can a town build new public spaces for discussing local issues neglected by national-politics coverage? What kind of social-media platform could we create that provides users with articulate counterpoints of view, with which they can constructively disagree?

Starting from these kinds of “How might we…” questions differs from a typical Silicon Valley approach, where you might keep pivoting in precisely what you provide, until you finally find a way to get sold. The end goal for us would focus more on civic impact. But certainly some pivoting would still happen, and we’d end up someplace quite different from where we started.

We’d want such entities to pick up one or more challenging questions about media’s civic roles and responsibilities, and then to spend multiple years researching the question, prototyping a solution, getting it out there. Ideally, if we want these entities to do real research, then that often should come out of our state universities. So does that all sound possible? I think so, particularly if we find a way to tax surveillant media, and to direct some of the revenue towards this kind of research and development. Does this all sound doable in present-day America? Maybe not immediately at a national level. Maybe more in a European context. But we definitely could start something like this at a state level. And again the broader vision would begin with establishing research centers, and having each of them pick up some central problem, conduct the research, design a prototype, and bring it out to benefit the civic marketplace.

Such entities could focus, “The Case for Digital Public Infrastructure” suggests, on initiatives related to content-creation (as in your example of sophisticated local-news coverage and policy discussion), on tool- or services-creation (perhaps with a non-surveilling platform like Mozilla’s Firefox as precedent), on social-science research (studies of social-media’s psychological and cultural impacts). So to close, could you make even more concrete how a few such representative projects might, say, foster democratic civic culture, promote a broad plurality of networked communities, facilitate governance within these self-regulating networks, and/or build out in additional ways a participatory, publicly accountable digital infrastructure?

So I’ll actually be starting a center around this set of ideas soon, at the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. This center, the Institute for Digital Public Infrastructure, will try to do a few things at the same time. First, obviously, we need to develop the vision. How can we get people on board with this idea that many of our media platforms really should be public?

Then I’d love to see us help bring about a plethora of distinct social networks, each with different rules and norms for different purposes. For instance, you can imagine a social-network space for people with a disease like type 1 diabetes (which I have), where participants might want high degrees of anonymity, high degrees of privacy. You might want to make this network exempt from ad-tracking. Americans often worry that insurance companies will see if they post anything in public about having a certain disease. So this network likely should have significant moderation. You’d want people to feel both very welcome and very comfortable. So you might have controls over this space, where a moderator could say things like: “Look, we won’t host a heated political debate here. We’ve shut down that particular conversation.”

But you’d also want other networks to operate by very different rules. For a while now I’ve wanted to build, for example, a small-town social network. I live in a town of about three thousand people, run by a town meeting. From a distance, this town meeting might look quaint and Norman Rockwell-esque. But up close, it can feel like an amazing pain in the ass in terms of getting anything done — say when walking through each line of the budget, with everyone in town capable of commenting on any single line. So I’d love for us to have a part-online and part-offline hybrid model. A couple days before a public discussion, people could start sending questions, and officials could start responding.

Of course you could try to just squeeze these functions into a Twitter or Facebook exchange, but that won’t work nearly as well. Those networks have their own specific purposes and corresponding designs — which tend to chafe at the kinds of restrictions that various communities and discussions might call for. You’d basically end up building your own new system anyway, which few people would then use.

So, architecturally, we envision three basic goals for these new networks. First, we’ll want an aggregator. Instead of relying on different sites or applications for all of these distinct social interactions, we’ll want to put them all in one place — much as you can navigate through all of Wikipedia, say, within one web browser. Why shouldn’t we have the same sort of social-media web browser, where you can find your favorite social networks all together (and can decide, for example: I want to see more of Facebook, or more Twitter, or more of the small-town network)? Here an aggregator actually makes smaller and less consistently trafficked networks, like the small-town network, much more viable. Most importantly, you yourself don’t have to remember to take the initiative to check in on them. They can simply show up in your feed when they get active again.

We also want this Institute for Digital Public Infrastructure to develop some sort of social- network construction kit. If I want to create a new social network with new behaviors, I might need to start from something like social-networking Legos or building blocks, so that I can just say: “Here’s how I want the space to work. Here’s who I want to let in. Here’s how I want it governed or not governed. Here’s who can govern it.” Once you have a sense of the different capabilities people might desire in these social networks, then you need to assemble a basic toolkit so that they can put their own networks together. Then third, you need some sort of central log-on system. Right now both Facebook and Google maintain such systems. That’s fine. But that also means these companies use these log-on functions as a surveillance system, so that they can watch us move all across the Web.

So that’s a start for building out a digital public infrastructure. In the long run, I’d also love for us to put together some kind of non-surveillant ad network. Ad networks can really help if you want to monetize a website. But maybe you don’t buy into the whole surveillant-advertising package. I bet a bunch of sites would willingly earn slightly less on their ads, in exchange for feeling better about making informed and ethical decisions about who does and doesn’t get tracked across the Web. I’d also love to see us take on projects like an auditable and transparent search. For now, it seems almost impossible even to imagine how researchers could answer a question like: “Is Google search biased towards or against any particular political candidates?” (especially when so much of Google’s algorithmic operations remains confidential).

Most basically then, we envision this Institute for Digital Public Infrastructure taking on four projects simultaneously. We’ll articulate this larger vision of an Internet that public entities (not private corporations) design and operate. We’ll do lots of the technical work actually building these systems. We’ll advocate for legal agendas enabling and supporting these forms of digital public infrastructure. And finally we’ll promote and provide really good measurement, really good social science. If we want to make the most powerful case for how these new social networks can benefit our collective civic life, then we’ll need to test and track and keep refining that proposition over time.