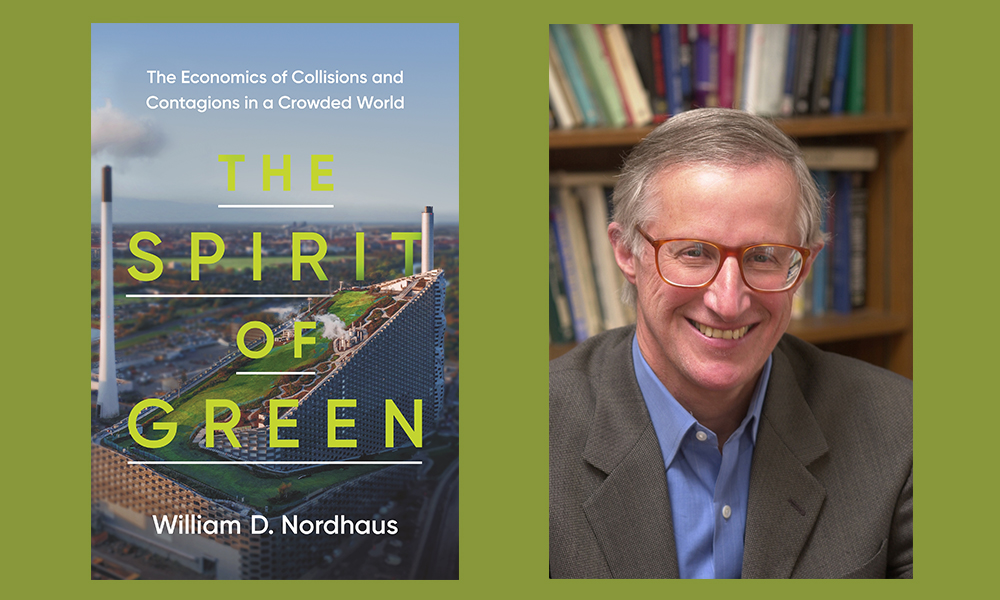

Why do we need to impose a global price on carbon emissions? Why should national governments take the lead in catalyzing and promoting low-carbon technologies? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to William D. Nordhaus. This present conversation focuses on Nordhaus’s book The Spirit of Green: The Economics of Collisions and Contagions in a Crowded World. Nordhaus, winner of the 2018 Nobel Prize in Economics, is the Sterling Professor of Economics, and Professor in the School of the Environment, at Yale University. His many books include The Climate Casino: Risk, Uncertainty, and Economics for a Warming World and A Question of Balance: Weighing the Options on Global Warming Policies.

¤

ANDY FITCH: We typically conceive of climate-change mitigation in reactive terms. But to take us to a working definition for “the spirit of green,” could you first sketch the basic contours of the well-managed society that this book models, and then introduce the spirit of green as a present-day aspirational force directing us there? What can the spirit of green take us to — rather than just take us from?

WILLIAM NORDHAUS: Over the past couple of centuries, we’ve developed a coherent way to think about how markets work, how they can lead to fabulous economic growth when operating smoothly, and how they can harm societies when functioning poorly. But we’ve lacked a coherent set of principles and practices for dealing with certain types of market failure — particularly when it comes to the other half of a well-managed society, public goods and collective responsibilities. So this book tries to complement or supplement or complete our discussion of how best to manage society, by spelling out some basic principles for managing our public life (not our private lives, not our families). It also links together the strengths of private markets with the strengths of these public goods and collective undertakings.

You can see a good example of us needing to marry the public and the private when it comes to this COVID-19 pandemic. Here I’ll just focus on one particular aspect in which we’ve had some dramatic successes, the development of vaccines. The United States, Europe, and China all have succeeded in their own ways on taking up this enormous challenge. In the US, this has meant tapping the strengths of our markets, especially the strengths of our scientific community and our pharmaceutical firms, to develop this brand new type of mRNA vaccine, in novel ways and in record time, surprising even the vaccine specialists.

We did that in part by deploying new conceptual tools designed to promote public goods. Pre-purchase agreements, for example, had been used in other areas, but here became absolutely essential as we went about developing these vaccines. We both applied public levers (such as pre-purchase agreements, or the subsidizing of intellectual property), and harnessed our private markets, all in pursuit of the broader public interest — in ways that never would have happened had private markets just been left to themselves. We showed that the public and the private can work extremely well together.

By extension, could we make concrete this book’s conception of sustainability? Could you bring in the principle of consumption substitutability, with its emphasis on attaining certain shared living standards, rather than on strictly preserving current conditions? And could you outline the limits to such substitutability — where we still might find incommensurate value in specific ecosystems or species or personal experiences?

Yes, and I’ll start with almost every big organization today having an office of sustainability. If you actually compare these offices, you’ll note some big differences in how they define sustainability. The concept of sustainability that I myself like to promote comes from an MIT professor of mine, Robert Solow. Solow described sustainability as promoting the collective welfare of multiple generations.

This conception of sustainability doesn’t prioritize any particular good, or tree, or environment, or climate. Instead our commitment to sustainability consists in our pledge to leave our society, our economy, and our public goods in strong enough shape so that the next generation (and the generation after that) can have living standards at least as high as ours. Good living standards in this most general sense depend not just on food and shelter, but also on robust civil liberties, and on the justice of our laws. All of this factors into the notion of sustainability. The good society’s standard of living will inevitably incorporate new and improved goods and products and services, but without imposing escalating spillovers, prohibitive costs, or irreversible scarcities. Consumption substitutability here operates as more of a general proposition. We won’t enjoy precisely the same goods and services that our parents or grandparents enjoyed. We’ll enjoy new or improved or sometimes alternative goods and services.

For example, Andy, you’re talking to me from Colorado. Towns like Durango, Colorado used to have their own active opera houses. Some of these quite charming buildings still remain. Some have been converted into bars or restaurants or museums. Still you might say: “Yeah, but shouldn’t we have preserved the standard of living that allowed Durango and Aspen to have their own opera concerts, with their own local orchestral accompaniments?” And I’d answer: “Of course not. That’s just too expensive today.” But this doesn’t mean we can’t find appealing substitutes. If you’re truly an opera fanatic, you can subscribe to SiriusXM Radio and listen to a satellite station devoted all day to opera. Or since we now have airlines, you can fly on a plane (at least when COVID-19 abates) to famed opera houses around the world. You also can routinely watch New York City’s Metropolitan Opera at your local movie theater. And if you ask me, as an opera fan, whether this makes up for losing Durango’s own opera performances, I’d say that, overall, consumption substitutability makes sense here.

So still with sustainability in mind, could you also flesh out what makes climate change such a nightmare of an externality, with the damages from emissions flowing far away from producers, absorbed into the atmosphere and oceans, creating a mess especially for future generations? And could we bring in the additional complication of individual nation-states, corporations, and private citizens receiving only a small share of the widely dispersed benefit for whatever efforts they make to address this problem (with idle observers, or even active polluters, benefiting just as much)?

First, when I emit a bunch of CO2 through my activities (by driving my car, or flying on a plane, or heating and cooling my house), I indirectly and maybe even unknowingly affect others. I affect the well-being of people in distant countries, and of people many decades into the future. Unless somebody points out my own contribution, I won’t see it, and certainly won’t feel it. And then even if I do devote myself to studying these devastating effects, I still can’t help noticing that I myself play an extremely small role.

At the same time, I myself directly pay perhaps one-trillionth of the negative costs that my actions bring about. In terms of, say, risks to public health, and volatility for agricultural production, and rising sea levels and coastal erosion, and more intense hurricanes and the eventual submersion of entire countries, I’ll personally pay just a tiny, tiny, tiny part of those big losses. Even a large, powerful population (like the United States has) will only experience a small fraction of the impacts from climate change, which will play out all around the world over the next several centuries. All of that makes this such a difficult externality to grasp.

Now to start honing in on the economics of climate change, first what makes a distorted profit motive (rather than any particular corporate CEO) “perhaps the biggest villain identified in this book”? In what ways do our society’s failings to address climate change stem from this central fact that “the price is wrong,” most basically because the social costs of emissions do not get internalized at their sources — sending faulty market signals steering our “economic locomotive…in the wrong direction”?

Once you start working on the economics of public goods, you start finding mispriced public resources across our whole economy. Most pernicious of all might be this underpricing of gases accumulating in our atmosphere and changing our climate. Carbon dioxide of course stands out. But if you look back just to 1990, you’ll see that no society in the world had placed a price on CO2 emissions. If you asked back then (as I did) whether we shouldn’t put a price on these emissions, most people would just look at you and think: What is this strange person talking about? Why would CO2 emissions ever cost anything, and why would we want to establish a particular price?

But I’d reverse the question here, and point out that by not putting a price on something, we in fact put a price of zero on it. We implicitly tell everyone in the market: “You can consider this unimportant. You don’t have to pay attention to how you use it. Treat it like sand at the seashore. Play with this free stuff all you want, and don’t worry about the consequences.” In that scenario, our markets provide no incentives to curb emissions, or to cut back on energy use. Being extravagant with your carbon footprint costs the same amount as being careful.

You can compare our indifference when it comes to carbon with our much more deliberate and efficient consumption of gold, or oil, or any expensive resource. By contrast, we end up squandering the resources of a healthy atmosphere and a reliable climate — which suggests a significant malfunction within our economy. So the spirit of green seeks to correct for that. We can, for example, incentivize much cleaner and more efficient use of carbon by establishing fiscal mechanisms to send this market signal of: “Consume less carbon. Find substitutes. Invent new machines and new capital goods and new automobiles that reduce your reliance on this expensive resource.” For consumers as well as producers, everybody, everywhere, should be receiving this message.

Two basic policy imperatives come to mind. First, we should put a price (whether or not a tax) on carbon emissions. We can debate precisely how expensive to make these emissions, but we need to make them more expensive than zero. And second, governments should take a very active role in promoting low-carbon technologies. Today we don’t have the technologies to meet our stated carbon objectives. We need to develop, for example, scalable carbon-capture. We need to move more broadly away from carbon consumption. About 80 percent of US energy and of global energy still derives from fossil fuels. So how can we get from 80 percent to near 0 over the next several decades? We only can do this through new low-carbon technologies. That necessitates governments playing a key role in coaxing and inducing and supporting the private sector (as well as, to a certain extent, the nonprofit sector) to develop these technologies. Again, we might take some inspiration from how, with this COVID pandemic, governments stepped in and made rapid vaccine production possible. We’ll need that kind of ambitious, focused, and careful effort on a much bigger scale now.

A high carbon price will help persuade people to invest in low-carbon technologies. Low-carbon technologies in turn will decrease the costs of climate abatement. These two developments can help reinforce each other. But it will be absolutely critical for governments to induce the private sector to get involved.

For one concrete example, where might proposed Green New Deal legislation constructively prompt technological innovations? And where might this bill reflect an unrealistic avoidance of price-raising measures, or over-rely on parochial national metrics?

I’d certainly consider the Green New Deal better than nothing. But I also don’t think we have to choose between the Green New Deal or nothing. My concern with today’s most discussed climate proposals is that they don’t really tackle the biggest challenges, and don’t utilize our most effective tools and policy instruments. First, they’re not realistic about what we’ll need in terms of carbon pricing. They basically just ignore that part, for fear of the political consequences. But we need to make carbon more expensive, and we have multiple means of doing that. We could do it through carbon taxing. We could do it through cap-and-trade type systems. We could combine these approaches. But we can’t just ignore this necessity.

Similarly, the plans I’ve seen so far don’t focus enough on putting major concerted effort into creating essential new technologies. They take up a more scattershot approach. They might have good provisions for retrofitting certain buildings. But again, we need much more than that. We need to develop transformative new building technologies, new energy sources, new batteries to power our new electric vehicles. I can understand the political and budgetary complications here. But none of that removes the basic necessities.

Another limitation I see in current proposals has to do with the emphasis on national measures, and the neglect of international coordination. Given the scale of our challenges, we can’t just let each country do its own thing. Countries will have to work effectively together. They’ll have to do something like raise carbon prices everywhere if we really hope to address our climate problems.

As we start to outline particular policy interventions, could you offer some comparative merits and drawbacks of relying on command-and-control regulatory imperatives, or market-driven fiscal mechanisms? Where, for example, might regressive or progressive impacts most likely manifest through these respective approaches?

We know a lot about the effectiveness of regulations, their strengths and their weaknesses. Command-and-control regulations to mitigate climate change turn out to be particularly weak and inefficient, for multiple reasons. First, we’d have to regulate so many different parts of the economy. And we might figure out how to regulate power plants or the airline industry. But we’d have a much harder time regulating countless small businesses, small commercial establishments, and individual households. Instead, we’d likely end up only regulating a fraction of our economy.

The EU, for example, has designed a quite advanced cap-and-trade system, but this still only regulates large corporations and power plants. This still only covers less than half of Europe’s economy. This still misses many industries and whole sectors where we could develop low-cost ways to reduce emissions.

Here before we get to taxes, could you offer a qualitative rationale for why we should pursue “optimal” rather than zero pollution, and for how a no-regrets principle might apply?

The clearest case might come from asking: given the severe consequences we face, shouldn’t we switch to zero greenhouse-gas emissions tomorrow? I’d answer: well, how would we go about that? Would we shut down all oil wells, gas wells, and coal mines, and not allow imports of these fuel sources? Of course that’s unthinkable. Here we should remember what happened just one year ago, in March 2020, when by shutting down certain parts of our economy, we reduced emissions quite a bit, but still didn’t get anywhere close to zero — and felt the extreme consequences of even that limited economic contraction.

So realistically, aiming for zero greenhouse-gas emissions tomorrow, or even 10 years from now, doesn’t make sense. We lack the technical capabilities, aside from basically returning to the Stone Age or beyond. So the phrase “optimal pollution” might sound like an oxymoron. But we do need to set our target somewhere between zero and today’s levels. We might decide: “Okay, let’s keep aiming for lower numbers over time.” Maybe we aim for relatively modest targets in the 2020s, but always getting more ambitious. Maybe we don’t reach zero overnight, but we do by mid-century (though that too sounds extremely ambitious). In any case, we can significantly reduce emissions from today’s levels at quite low cost. We might not reach zero, but with effective carbon pricing and low-carbon technologies, we can certainly reduce some 20 or 40 or 60 percent over several decades.

I won’t ask you to verbalize precisely how you arrived at your preferred $40 per ton price for CO2 emissions. But for the politics of getting even that comparatively modest tax enacted, we’d of course have to factor in how any such proposal would catalyze its prospective losers (most conspicuously, some of today’s most profitable and powerful firms), while bringing only dispersed benefits to its prospective winners. And then, even if passed, such a tax would face significant chances of soon getting repealed, perhaps through Congressional reconciliation processes, requiring just the thinnest of majorities. So what proactive complementary policy measures would you stress for building the broadest, sturdiest base of support?

Let’s start from the essential need to raise the price on carbon emissions. We could do this through a tax, or through a cap-and-trade system. The cap-and-trade model has had much more widespread implementation around the world, though personally I consider a carbon tax a more effective instrument.

China does cap and trade. Europe does cap and trade. According to the latest World Bank survey, roughly 80 countries now have some kind of carbon-pricing plans, primarily cap and trade. I think countries just find this easier to implement. I mean, each situation poses its own challenges. Europe doesn’t necessarily have a strong anti-tax streak. The EU, however, possesses expansive regulatory authority, but not equivalent tax authority. Canada, by contrast, has taken a carbon-tax approach. Each society has its own institutions and policy options and political calculations.

In the United States, for example, a cap-and-trade system would probably work better, most basically because it takes much more political effort in the US to dismantle a regulatory system. You can’t just rely on budget reconciliation. Even an anti-regulatory administration faces significant procedural hurdles, as we saw during Donald Trump’s presidency. Or think of how long the 1990 Clean Air Act (which imposed a cap-and-trade system on sulfur) has stayed in place.

So in this US context, I would happily set aside my personal preferences for a carbon tax, if I could implement a sufficient cap-and-trade system. In the end, they’d have pretty similar effects. Second-generation cap and trade (which includes auctions) looks almost just like a carbon tax. And then we have sophisticated models such as British Columbia’s, where a carbon tax pays for an income-tax rebate for much of the population (as well as for a corporate-tax rebate). You can raise, say, $10 billion this way, and then rebate, dollar for dollar, the $10 billion to local households. You can rebate on a per-capita basis, or in a more progressive way. You can put half of the 10 billion towards rebates for low- and middle-income households, and half towards subsidizing and implementing low-carbon innovation. I’d personally prefer that hybrid approach, but again you’d have multiple options, and you could tailor your policies towards a particular local context.

Then to further ratchet up the political challenges, why will single-nation climate initiatives prove not only insufficient, but often unsustainable? Why do we need (and how does a global collectivity implement) a harmonized price accurately reflecting the social costs of carbon? And to offer some sense of relief in the face of this daunting task: what makes a globally harmonized price “all” that we need for an efficient market mechanism to take hold?

You don’t want one country making a huge effort while another country does nothing. That’s a classic recipe for stress, conflict, and unsustainable policy design. So first you need to bring together as many countries (particularly high-income countries), representing as much of the world economy and the global population, as you can. So this would need to include China. It would need to include India. It probably wouldn’t at first include much of Africa’s interior. But it basically would address 80 to 90 percent of global emissions. You need that kind of scale to significantly slow the growth of atmospheric concentrations.

Fortunately, many of these energy-intensive nations rely heavily on international trade. That makes these countries very sensitive to the loss of a competitive edge. So if one country prices carbon at $100 a ton, and another country at 0, this would immediately complicate both countries’ trade prospects. It would inevitably bring further consequences, such as incentivizing certain industries to demand exemptions (as we’ve seen in the EU), or certain countries to impose tariffs and protectionist measures and so on. But if each of these countries recognizes the pragmatic value in agreeing upon a carbon price, then you don’t need any further trade measures to offset these policy frictions.

And if it sounds impossible to get most of the world agreeing on a carbon price, how could a climate compact or club help to take us there? What makes enforcement potential among club members (and penalties for nonmembers) so crucial — and so different from our recent history of global climate initiatives?

So we start from a completely muddled picture, with various countries all pursing different interests. To some extent, this disorganized situation comes directly from an almost fatally flawed approach to designing international climate agreements. We’ve prioritized voluntary agreements. With the 2016 Paris Accord, for example, countries developed their own national pledges and policies. But we have precisely no enforcement mechanism to ensure that countries fulfil their pledges (separate from the question of which countries have made sufficient pledges). We basically have an agreement made up of hollow promises.

For the 1997 Kyoto Protocol, countries made hollow promises. Then two decades later, they dropped those long-since-abandoned pledges, and made new hollow promises. Unlike important international agreements which have succeeded, our climate agreements have lacked strong incentives either to join or to abide by one’s commitments.

So how might the history of global tariff reductions provide a more useful model here?

Well if you look back to the 1920s, the US average tariff rate was 50 percent. Today it’s between two and three percent. In the 1920s, most countries averaged maybe 30 or 40 or 50 percent. Today’s high-income countries average closer to three percent. And this transformation didn’t happen by accident. It required long rounds of very tough negotiations. I served in government during the Tokyo Round’s negotiations. I remember how those discussions went on and on and on.

But we also needed more than negotiations. We needed mechanisms to penalize countries who didn’t abide by their agreements. From time to time, we still see trade wars flare up. Donald Trump of course kept starting trade wars. We had a solar-panel war, and a washing-machine war. We now have an airplane war. So we need enforcement mechanisms with teeth, to keep countries honest. We’ll need penalties to hold climate-club members to account. We also can use the prospect of external penalties to incentivize countries to join this club in the first place.

To close then by returning to a present-day US context, one in which green causes tend to get associated with Democrat or further-left politics, what case would you make to self-identified conservatives on why they should actively promote appropriate carbon prices — correcting for market distortions, delivering vital information that directs all market participants to enhanced efficiency, and rewarding those who play by robust market rules?

As we’ve all seen over the last several years, US conservatism has divided into two camps, characterized by more classically liberal approaches from the Reagan and George H.W. Bush administrations (exemplified in people like George Shultz or Martin Feldstein), and by more populist visions (associated with Donald Trump). US conservatism today doesn’t really offer any coherent collectively shared views.

Now specifically in terms of climate, the more traditional conservative camp has come around considerably over the past two decades, and today sounds much more activist on climate change, and even strongly in favor of carbon taxation (not just carbon prices, but carbon taxation). This particular group of conservatives has managed to stay much more internally coherent in its minimal-government approach to managing the good society. I have a lot of sympathy for this view that designing well-honed fiscal instruments, rather than imposing expansive regulatory instruments, would prove much more effective at tackling climate change. A vast majority of economists say the same.

A responsible conservative approach, like a responsible progressive approach, recognizes the existential stakes faced by parts of our global society today, and certainly parts of our natural environment. That conservative approach supports tackling these major challenges in an appropriately ambitious way, and it emphasizes carbon taxation as the most efficient, effective, minimally intrusive policy mechanism for slowing climate change. Among responsible conservatives, and definitely among economists, I don’t see much disagreement on the importance of achieving these goals.