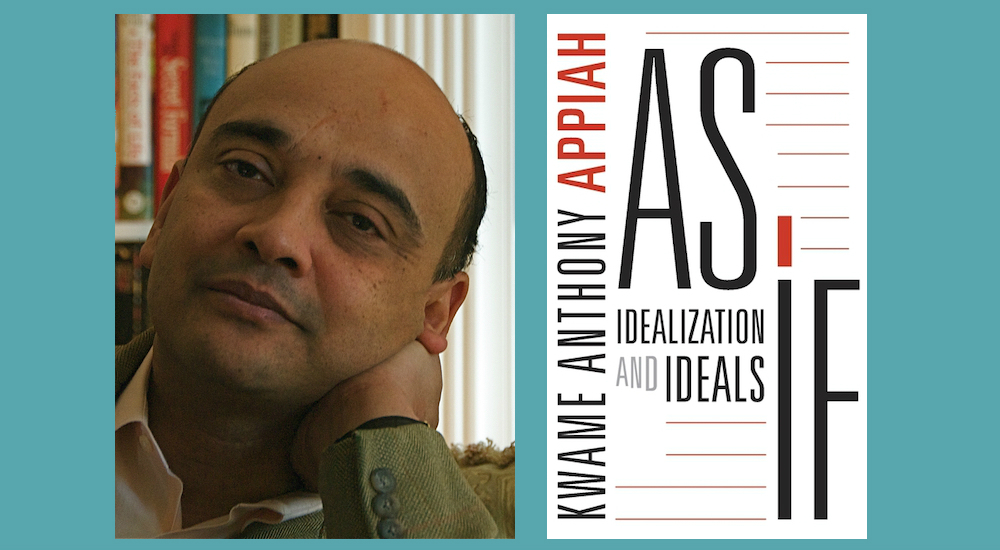

When does debunking a theory not yet sufficiently determine whether we might benefit by applying that theory? When do “unrealistic” theoretical models nonetheless prove the most constructive? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Kwame Anthony Appiah. This present conversation (transcribed by Phoebe Kaufman) focuses on Appiah’s As If: Idealization and Ideals. Appiah is a professor of philosophy and law at NYU. He explored questions of African and African-American identity in In My Father’s House: Africa in the Philosophy of Culture, examined the cultural dimensions of global citizenship in Cosmopolitanism: Ethics in a World of Strangers, and investigated the social and individual importance of identity in The Ethics of Identity. He also has written three mystery novels. Appiah has been President of the PEN American Center, and serves on the Board of the American Academy of Arts and Letters, the New York Public Library, and the Public Theater. In 2012 he received the National Humanities Medal from President Obama. In 2018 he is chairing the Man-Booker Prize committee.

¤

ANDY FITCH: An impulse towards the “as if,” towards the “quasi” in Latin terms, might seem to sit uncomfortably close to present-day polarized, often quite paranoid political conversations. So at first, in trying to assimilate a working definition for “as if” practices, I couldn’t stop placing these alongside the pathologized (nonetheless quite human) “as if not” of Freudian disavowal, the tendency to structure one’s behavior around the functional denial of a set of premises one might cognitively recognize as true (with unimpeded contributions to climate change, even by non-skeptics, one glaring example). Or your own book sketches a continuum on which, from one side, psychopathic tendencies might allow individuals to pursue their need for control by acting as though something they know false were true (say, that a barbaric act is tolerable), and, from another side, cynical propensities might coax a person to posit that the inevitable corruption of one’s peers justifies one’s own questionable behavior. So here, to help us step outside diagnostic approaches presuming a dysfunctional “as if” mechanism, could you offer a brief intellectual biography that traces your career-long efforts to articulate a more generative approach to the more constructive aspects of an “as if” orientation?

ANTHONY APPIAH: You’re right about this being a career-long thing. My doctoral dissertation explored how we should conceptualize the role of certain types of belief in explaining meaning. I considered, for example, a proposed explanation for how we use conditional sentences. This proposal involves supposing that people have degrees of belief — not just believing or disbelieving, but degrees in between. The rules or laws proposed for the conditional get defined in terms of these degrees of belief, which often get called “subjective probabilities.” These rules seemed definitely interesting and perhaps worth defending, but it didn’t look clear how one could go about supposing that people’s beliefs had strengths, or especially that you could measure the strength of these beliefs in order to confirm that they conform to the logic of probability (that if you believe to degree X that it’s snowing, for example, then you also believe to degree one minus X that it’s not).

So I got interested in how you could ascribe to people these subjective probabilities or degrees of belief. That people actually had such precise and coherent degrees of belief struck me as evidently false. This presupposes that our thoughts present a very tidy logical structure not evident in the actual reasoning behavior of any actual, however “logical” person. So then I had to think through how one could treat people as if they have these internal states conforming to these rules. I said: “Well, it looks like we’ll need an idealization where we treat people as if they are logical in a way they’re not.” Nobody objected [Laughter].

But this broader question stayed with me: why would we ever find it useful to try and understand people’s behavior by supposing their thoughts have a structure that they evidently lack? That question would return in many contexts later on, in relation to all kinds of things, where we put forward these pictures to understand the world, while knowing these pictures to be mistaken. When Galileo explains the cannonball’s fall from the Tower of Pisa, he knows perfectly well that the air’s forces of resistance factor into this fall, but he considers these forces small enough to ignore, so he tells a story about calculating velocity in which he leaves out details that he, you, I know perfectly well won’t make much difference.

And that picture of people possessing degrees of belief didn’t just come from me and some others thinking about semantics. This picture actually underlies, for example, most of modern economics. Economists treat people as rational agents seeking to maximize profits in some general sense. Again economists, often quite bright, and recognizing people do not behave super rationally, nonetheless use these rational pictures to explain human behavior. This “as if” approach doesn’t just get applied to the physics of dropping cannonballs, or to fancy linguistic theory. Our ordinary thinking contains countless examples of embracing a picture we recognize as in some sense flawed.

So when the American Philosophical Association invited me to give a series of lectures, I decided to say something about how idealization plays out in different contexts, in part because it seemed important for so many fields of research. I began as any humanist would: I considered what people in the past and at present have said about the subject. I had known for a long time about Hans Vaihinger’s Philosophy of “As If” book, which I had first looked at while writing my dissertation. I discovered it (this book was incredibly famous when it came out, though more or less forgotten by the time I found it) by looking around in the library. Vaihinger too had noticed the pervasiveness of idealization: from mathematics, to economics, to philosophy, to social sciences, and so on. He had noticed that earlier philosophers often committed to such views. Kant had decided that we should behave as if free, although Kant also considered us, from a certain point of view, as causal machines governed by deterministic laws.

Here Vaihinger makes the related and very useful point that, as cognitively imperfect creatures, as not entirely reasonable, even at our best we can only build imperfect pictures of the world — which we recognize as imperfect. Though imperfect, these pictures remain the best we’ve got for the present purposes of guiding our actions and helping us decide what to do and how to bring about what we want to bring about.

This leaves it to us to remember what we have left out, and where “as ifs” shape our picture, and what we use them for, and what other parts of our head might think. To continue from the Galileo example: when you try to send a couple of astronauts to the moon, it turns out you can’t use Newtonian physics to calculate the correct trajectory. You have to incorporate Einstein’s account of relativity. But you can leave that out with most everyday Earth-bound engineering calculations.

You do though, at times, want to recognize consciously: I know I’m leaving something out, but that seems OK for my purposes in using this picture. And this type of thinking means that we’ll need many pictures, which we’ll want to use for our many different purposes. What we leave out in some circumstances won’t make sense to leave out in other circumstances. But allowing “as ifs” to guide our actions can, when used appropriately, help quite a lot with what Vaihinger called “finding our way about in the world.”

In terms of this question of what uses we might make of particular pictures, I would assume that, at least to many American audiences, “as if” operations often sound closest to vernacular conceptions of pragmatism — a sort of perspectival utilitarianism that we electively deploy in order to manage the world (and ourselves) as deftly as the present moment allows. Here could you situate “as if” procedures alongside (and, when useful, as distinct from) pragmatism? Certain formulations you offer, such as that “Vaihinger obviously differs from at least one strand of pragmatism…. He thinks that there is a gap between what is true and what is useful to believe” make good sense. Pragmatists generally seem less inclined to describe themselves as pursuing a fictitious line of thought. But something about your qualified “at least one strand of pragmatism” phrasing suggests you have more to say about potential overlaps and distinctions between these two theoretical approaches.

Well, as with many named philosophical traditions, it can be hard to capture the essence of pragmatism. Indeed, one might think of pragmatism more as a collection of disputes than a collection of agreements. Frank Ramsey, one of the philosophers from whom I’ve learned the most (and an English philosopher, so looking at America from across the seas), once described the essence of pragmatism as the idea that beliefs are states on which we act. Again, according to Vaihinger’s model, we form beliefs in these idealized pictures in order to find our way around, in order to do something. So if you define pragmatism this way, then Vaihinger definitely seems some kind of pragmatist. But some people also might embrace a “semantic pragmatism,” which claims that what is true just is what is useful to believe. This kind of pragmatist seems quite different from Vaihinger, who might recommend that we act on a theory even while we recognize this theory as in some fundamental sense wrong.

Now you might ask: does the use of a theory to get yourself about amount to believing it? I would say: not necessarily. Two people might apply the same theory, even if one believes the theory correct while the other person disagrees. Vaihinger wants to explore this gap between what we believe true and when we find it useful to behave “as if” we believed something true. So belief here means to treat as true, and Vaihinger asks us (as do many other thinkers, in different ways) to think about when we believe tout court, and when we are just acting as if we believed (in some context, for some purpose). Of course, if you acted on a proposition everywhere and for every purpose, that would amount to believing it. So this brings out the context-bound character of believing “as if.”

Here, to continue describing how “as if” approaches might parse actions, beliefs, and values, could we also continue situating some of your book’s more technical terminology alongside, say, vernacular conceptions of “ideals” and “idealization,” and perhaps throwing “idealism” into the mix? Could you start to clarify how, though at first we might conceive of an ideal as some sort of fixed, perfect, timeless, transcendental limit case, we also can conceive of idealization as more of a roving conjectural/exploratory/ever-provisional mode of interrogative engagement? Along the way, we might want to sort out where idealism as a mode of ethical valuation might fit, or various philosophical strains categorized as Idealist. We could consider your reading of John Rawls and of Rawls’s perhaps mistaken conception of how idealization plays out in his own A Theory of Justice. We could outline a broader range of quite diversified idealization projects: from Thomas Hobbes to Adam Smith to Jeremy Bentham to Alexis de Tocqueville to Martha Nussbaum, Amartya Sen, and beyond. But however you see fit, could you sketch your own ideal/idealizing approach to how we might deploy these terms and practices amid both analytic and everyday efforts to shape and enhance our lives?

We use much “as if” thinking when developing accounts of justice and of the good. Hobbes provides a picture of human beings as fearful, self-interested, but also roughly equal in power, so equally dangerous to each other. If we can agree to this picture, Hobbes argues, we can see that if we don’t accept the leviathan for our state, then our lives will turn out nasty, brutish, and short. Now, that picture of the self-interested, rational agent overlaps in some ways — but also obviously departs from — the picture Adam Smith offers in his economic writings (not the work about the moral sentiments, but in The Wealth of Nations and so on). Of course even Hobbes also notices that some people actually like each other, and don’t fear each other all the time. He characterizes himself as a particularly fearful person in his autobiography. He says: “Fear and I were born twins.” But he wants to sketch a broader picture of human beings, as part of arguing for a certain organization of the world, in terms of giving the state great power to stop us from getting in each other’s way — as the best social model we can build.

Smith, however, asserts that if we can picture ourselves as rational, self-interested agents, then we should support a hands-off approach to managing the economy. He argues that if two roughly rational people freely agree to an exchange, then it must make both of them better off. Otherwise, why would they both agree to it? A world of free-market exchanges will mean a world in which every transaction makes both parties better off. Though again, having made arguments that treat us as rational, self-interested economic actors, Smith then writes a whole book on the moral sentiments — as this important other part of human psychology. He brings back psychological aspects he had deliberately left out of his economic theory’s “as if” picture. And even on economic questions, Smith’s picture of human behavior doesn’t always give us a clear and useful theory. We can make that objection to Smith, which differs from objecting to Smith on the grounds that his theory leaves something out. Every theory leaves something out. We can’t think about everything all at once. We have to simplify, abstract.

Rawls does this when thinking about justice. His first book, A Theory of Justice, essentially proposes to see what justice would require if a group of individuals agreeing upon an explicitly idealized picture of human psychology gathered to organize society. Rawls makes very clear what assumptions this group shares. He considers this group’s members, for example, much better informed than most actual people. He assumes that these group members know a lot about economics, that they do not envy each other. Rawls explicitly acknowledges that he knows people do, in fact, envy each other. But he wants to characterize people “as if.” His book doesn’t ask what actually would happen if you put a bunch of people together. He asks: what would a room full of people equipped as astute psychologists and with adequate information agree to? You can object to this line of questioning in various ways. One is to say: “At the least I hope for some specific effects. Some specific effects would be really important.” So maybe Rawls hasn’t built into his scenario some things you ought to know in order to answer this question most productively. Or you could consider it much more important to reflect on what people with real psychologies might agree to do. You could object in various ways. The point is, though, that Rawls, like Hobbes, like Smith, does a pretty good job of introducing his original “as if” position, and of drawing further conclusions about people from that. You might reject Rawls’s particular “as if” position, that is, without rejecting Rawls’s decision to work from an “as if” position.

Still, let’s say you decide to raise a slightly different objection (as I do), and to ask: how much does it help our understanding to picture an unrealizable world of total compliance? Could we help ourselves more by picturing a world of partial compliance, and trying to model society based on that more realistic conception? Now, Rawlsians will have responses to that question. Most basically, they do still find it illuminating to think about the behavior of actual people in terms of this explicitly counterfactual picture. They echo the classic Vaihegerian idealization, which proceeds according to what will be most useful. Like Vaihinger also, they might claim that we can’t help but start from such a picture.

And my own take on an idealizing tendency doesn’t differ much. I do though particularly appreciate, in Amartya Sen’s more recent work, Sen’s claim that you don’t always need to understand the messy, actual world in relation to some ideal world. You don’t need to picture the best possibility in order to make things better. You just need to know how to make things better. This argues for a different kind of political philosophy. It starts from where we are, and seeks to find which way is up — as opposed to placing an ideal before us, and imagining how we can get there.

My own personal skepticism comes from the sense that we don’t have a very good grip on how to describe or define the ideal. I find it hard to keep clear in my mind, for example, the picture of a society completely rid of racism and sexism, which continues to have racial categories and to distinguish between men, women, and some people who identify as neither. That picture seems so remote from our present. My imagination can’t hold onto it. But I do know that less sexism would be good, as would less racism. That seems clear without any need to clarify further what an ideal world would look like with respect to questions of identity. So perhaps in this scenario, too much focus on perfection, on ideals, can get in the way of us making things better. Still my book does offer as its main claim that we need lots of pictures and that we need pictures for many different purposes. And here again Rawls’s approach of trying to define an ideal society might actually in certain contexts help us make our own society better. But reflection on a just society won’t tell you precisely what to do about racism. It doesn’t tell you precisely what to think about asylum, because an ideal world would have no racism and no need for asylum.

You make a similar case in terms of philosophical arguments for how a rational person should address the irrational components of his/her being: in fact, no such component could exist in this person.

That’s the perfect case. We need to qualify our sense of what an irrational person (which means all of us) will gain by imagining what a fully rational person would do. A fully rational person already would have deleted the irrationality!

Still pursuing working definitions for several significant terms from your book, I wonder if we also could pause (as the Janet Jackson song does) on the perhaps particularly loaded term “control.” Untruths, in Vaihinger’s conception, can prove nonetheless quite useful if they help us to control the world. Such pursuits of control even can appear, from certain angles, anti-tyrannical, as when Vaihinger appeals to the utility of fictions not only to manipulate the external world but to help manage, potentially to help moderate, ourselves. Still I can’t help bringing, say, Heidegger’s wary approach towards technology, or classical Greek formulations of self-destructive hubris, into my understanding of how human-structured control plays out. I’d love to hear you address, for instance, the phenomena by which the more successful a (true or untrue, verifiable or unverifiable) belief becomes as “an instrument for finding our way about more easily in the world,” the harder it gets to recognize that this instrumentally helpful conjecture remains just that — a conjecture, not a truth, even as we semi-instinctively organize a world picture, a social structure, a technological regime as though oblivious of any such distinction. Here we could consider physics, mathematics, economics as fields in which “as if” principals have led to striking advances in our lives, and how such gains both assist and impede our abilities to recognize where constructive “as if” thinking still shapes these fields. Or when you mentioned Vaihinger’s eventual obscurity as a thinker, I couldn’t tell if I should consider this a success or failure on his part — in terms of his approach getting absorbed into various theoretical projects which no longer need to self-consciously sort “as if” mechanisms. Vaihinger of course does make the case, as do you, that successful idealizing should not remain static, that when such conjectures help us to build and grasp useful models of the world, we need forever to keep refining those idealizations, putting more and more of the now discoverable world back into these models.

This connects well with some other work I’ve done, which insists on the importance of what philosophers call “fallibilism,” where you don’t abandon your beliefs, but you do think of them as always revisable, open to further exploration and revision (even on really central questions).

Now, I think this view in which we manage the world by combining many incompatible pictures helps with that. For one quite specific case, I think Alan Greenspan’s forgetting the “as if” character of a seemingly rational picture explains why he was so genuinely perplexed by what happened in 2008. What happened couldn’t have happened in an economy where people pursue rational self-interested ends. Their greed wouldn’t have allowed them to overlook the fact of credit being given to people who never could pay up. Building that irrational impulse into our picture might have helped us stop this crisis from developing in the first place. Greenspan himself eventually said he had learned something [Laughter]. He had learned that models persistently present us as rational, self-interested actors — but that they only work for certain purposes. It turns out that these same economic models fail us in other situations.

Now, in theory, lots of economists already knew that. Behavioral economics tries to build models assuming fewer truths about our supposed rationality. But of course it’s very hard to build powerful general pictures taking account of all the details. Some people, for example, care deeply for their spouses, children, and even their country in ways you cannot call self-interested. Self-interest typically won’t lead you to sacrifice your life for your country. So here again one needs to ask: does my model fit all contexts in which I want to apply it?

For another specific example, as an undergraduate medical student at Cambridge, at some point studying biochemistry, I once interviewed Jacques Monod, who got the Nobel Prize for figuring out (among other things) the ways in which E. coli manages the genetic production of lactase enzymes, the ones it uses for processing milk sugars. I drove Monod to Heathrow airport, where there was a fog, so we ended up talking for a long time in the airport cafe. At one point, I asked whether he thought the model he had proposed provided the main tools needed for thinking about genetic regulation, and he said yes. The next 40 years of genetics showed him wrong [Laughter]. We now have a massively more complex picture of genome regulation. The mechanism Monod identified remains one very important component of our understanding of bacteria, of course. But even very smart men and women, Nobel Prize-winning biochemists, need to remember that the pictures they build work well for some purposes, but very likely will not apply to every purpose, even within their own specialized field.

Sometimes people say that focusing on fallibilism prevents us from taking our own beliefs with full seriousness. But you can take your view very seriously while still understanding that it might be wrong. Again, we find this fact reflected in subjective-probability theory, when it claims that for any belief you possess to degree X, you also believe to one minus X that this belief might be wrong. So the scientific method no doubt can help us get closer to a correct picture, but by and large we stumble along in the universe, trying to make sense of it all. Sometimes we stumble upon very useful stuff, good for lots of purposes, and we should celebrate that. But philosophers also remind us not to bet everything on anything.

Of course thinking this way does not come easy. It demands great discipline. History helps us see this. Anthropology helps us see this, as do certain philosophical arguments. And that great world of imaginative “as ifs,” literary fiction, can be a great guide, too.

Amid that ongoing need (and often failure) to recognize the provisionality of theory, your intro describes this book as a “gentle jeremiad.” But your book in fact doesn’t run that long, and doesn’t sound so bitter. As If might espouse something like a Charles Peircian emphasis upon selecting manners of belief which will produce preferred outcomes (rather than discerning the supposed correctness of a given belief), and yet, perhaps in proper pragmatic fashion, your book doesn’t offer some long gloomy litany of all the corrosive present-day practices that seem to push in opposite directions. I admire As If’s more buoyant approach, but I also would appreciate discussing a bit the types of interrogative, discursive, conversational pivots this book does (again quite gently) call for. For instance, if we can accept that the pursuit of infallible truth never drove most crucial processes of human inquiry in the first place, how might that reshape what often seem like pervasive present-day inclinations towards debunking alternate viewpoints (sometimes those of apparent rivals, sometimes one’s own past presuppositions and political contradictions through a confessionalist purge) as a sufficiently inquisitive, persuasive, reconstitutive interpretive/ethical/artistic/political outcome in and of itself? If we can acknowledge that finding a world picture internally inconsistent (or simply different from our own successful model) does not adequately determine whether the world picture in question proves potentially useful and thereby worthy of consideration, which patterns of self-reflective, interpersonal, institutional, societal engagement could this particular acknowledgment most positively recalibrate? Or to shift slightly the angle of inquiry here, throughout As If I kept recalling queer theorist Eve Sedgwick’s concern that paranoid critical projects (those pursuing the primary goal of exposure, of revelation — again considering this mode of disclosure a sufficient, or at the very least an all-eclipsing endeavor) tend to constrict themselves to a startlingly narrow affective range, warding off surprise attack perhaps, but also choking off more expansive or exuberant or galvanizing prospects. So in a world in which we have ample cause for suspicion, in which we might feel the perpetual obligation to tear down the establishment of alternative facts, could you nonetheless make the most proactive case for how and why, today, right now, we can and need to fuse incisive pursuits of the truth with a diversified pursuit of “the truth about what is possible,” here catalyzing “our most astonishing human capacity: the ability to access ways the world is not but might have been”?

If you think that something goes wrong with all these pictures, then I would offer a lovely verse from Sir Richard Burton, where he says: “Truth is the shattered mirror strown / In myriad bits; while each believes / His little bit the whole to own.” I want to accept something about that scene Burton describes, but to deny that each of us only can gather our own little piece. I want to say, first of all, that I myself have more than one piece. I have many pieces of this shattered mirror. The pieces, unfortunately, can’t all fit together and be assembled into one complete and coherent picture. The pieces only reflect their particular truths, and reflect even these imperfectly. But if you think of your meta-picture that way, you will be more inclined to engage in what I call “cosmopolitan conversation.” You’ll more likely recognize that every picture and every person gets something wrong. You won’t find it terribly interesting that somebody got something wrong. You might even find it more interesting to figure out instead what they got right — what perhaps only can be glimpsed about the world through a picture that’s wrong about the world in many other ways.

Of course many cultural and political models oppose cosmopolitan conversation. Some offer fundamentalist religious pictures, or some New Atheists seem to think that finding mistakes in the Abrahamic traditions proves that we should end those traditions. Such individuals might not grasp that those whom they attack often recognize the imperfections of their own religious picture. The New Testament says that “We see through a glass darkly,” which gets echoed by Burton’s shattered mirror imperfectly representing things. So here again, what I would find much more interesting in criticizing Abrahamic texts would involve not showing that this picture contradicts itself, but showing that this picture can lead to terrible consequences — say in terms of how gender relations between men and women get prescribed. And such a critique also should acknowledge that these very same texts provide very important models of justice and peace and love.

Winston Churchill once said about my grandfather: “There but for the grace of God, goes God” [Laughter]. And my very wise mother once said to me, a teenager: “I want to warn you, because you’re a bit like your grandfather. You think that if you win the argument, you’ll change the other person’s mind. But all that happens with the kind of argument you make is that people walk away and wonder what hit them. Five minutes later, they’re thinking exactly what they thought before you conducted your assault.” That’s not a productive way to interact with people. To push them positively, you need to make as much sense as you can of their own perspective. You need to understand how their picture allows them to do things you consider deplorable. You need to engage their picture in a way that allows them to see the problem it brings about.

None of this is anti-realist. I believe that a world exists out there, containing its truths. But I also believe that for all interesting and complicated matters, nobody has a fully adequate picture, and that includes myself. So when Robert Frost (no liberal, even though he spoke at Kennedy’s inauguration) describes a liberal as someone who can’t take one’s own side in an argument, I think he points at a genuine virtue of liberal-mindedness. The person who could adopt an opposing position says: “OK, I can see something valuable in your perspective. I can say that your picture might be useful for some purposes. I can adjust my own picture accordingly. Maybe my own picture still holds for many purposes, but it doesn’t frighten me to also consider yours. I don’t care about winning an argument and proving you wrong. I’d rather accept anything useful that I can find in your position.” Radical confidence in one’s picture has a bad history.

Returning now to Burton’s shattered mirror and what we might make of it, I’ve asked for a decent number of definitional parsings, and maybe we could further flesh out some of these by considering something more like an embodied practice, let’s say here of functional isolationism (with maybe for the closest vernacular point of reference, the concept of “compartmentalizing”). I’d love to outline some lived personal experience and broader institutional/disciplinary enactments of functional isolationisms. Here I think, again, of your preceding work both arguing that empirical racial categories do not exist, and yet acknowledging the need to assign and potentially reinforce racial categorizations (say through affirmative-action policies), in order to address historical patterns of discrimination that have played out along such lines. I value how your book can appear quite accommodating to a wide range of potentially polarized present-day cultural perspectives, while nonetheless articulating pointed historical claims, such as that “almost none of the property in the world today” has been justly acquired or justly transferred throughout its existence. I appreciate your quite dexterous recommendation for our own parceled/kaleidoscopic approximation to the reasonable (“our imperfection…allows us to work, not with a single picture of the world, but with many…. And because they are incompatible with one another — because they cannot all be true — we have to be able to keep them separate if we are not to be drawn into incoherence”), and how reasonable such an approach sounds when you state it, and yet how frustrating that approach might seem to utopian-tending communities committed, say, to the construction of a more totalizing world picture, to the deliberate blurring of artistic, critical, philosophical, psychological, idealistic, economic, prosocial agencies, formulations, and commitments — as the only potential way to combat prevailing hegemonies, and to reshape the world towards more progressive ends. And so I wonder how you might describe your own lived practice of embracing the poetics and the potentially fraught politics of a functional isolationism.

Well the trouble is that we aren’t equipped to bring the whole together. Mid-20th-century scientific visions sought to integrate all our knowledge into one big picture. But we’ve ended up with quite the opposite. We have lots and lots more scientific pictures, but still haven’t figured out how to integrate them. A chemist learns two theories for the chemical bond, and uses one sometimes and sometimes another. A doctor sometimes thinks of a patient in biochemistry terms, sometimes in terms of organs and the organism as a whole, sometimes about her mental state. No theory fully integrates this all into one coherent picture. You just have different pictures, and would waste too much cognitive energy trying to pull them all together all the time. Though of course you can take two specific incompatible pictures and try to figure out how to put them together, and that can be a fruitful intellectual project.

That happened with the invention of molecular biology in the 1950s. DNA’s discovery made it possible to connect a molecular-level understanding of the cell with a functional understanding of how reproduction transmits properties across the generations. Sometimes it’s a good idea to pull two pictures together. Multidisciplinary work happens all the time in the sciences, bringing together different pictures to answer overlapping questions.

Then in terms of living within this more general mode of functional isolationism, your question of how racial categories should be assigned gives a good example. I persist in thinking that we make a mistake when we unreflectively map racial categories onto biological properties. I continue to believe that, though I also know many people do not believe that. Lots of people still consider racial categories as grounded in profound biological differences between kinds of people. That seems wrong for the purposes of analysis, but I also find it pointless to keep banging on about this. When the NAACP asks for money to fight racial discrimination, I don’t say: “Unless you admit to me that your categories do not cohere, I refuse to give you any dollars.” My preferred way to put such concepts together involves devising a notion of racial identity which stays fuzzy and non-biological, but which we still can use for purposes of social analysis. But again, I begin not by insisting that the NAACP accept this view. I don’t mind them developing another picture because, most of the time, the NAACP using this picture won’t do much harm. On the other hand, when Nazis and the alt-right use similar pictures, it does do harm. So again I try to address incoherent racial claims not because I inevitably distrust the people making such claims, but because I worry about these claims producing bad effects.

Our world is full of people with false views. There also are millions of truths not worth storing away in your head, and also truths perhaps too painful to bear. You’re better off with a resonant truth than with a resonant falsehood, but I won’t spend my time battling, and I don’t think you should spend your time battling, people who have wonderful theories about the wheel of rebirth, the body’s resurrection, the halakhic impermissibility of organ transplants. You would be a kind of Don Quixote, battling tiny windmills, thinking you fought giants.

So in terms of everyday practical advice…when my mother was still alive, I went to church with her because she liked me going to church with her. She was a believer and I’m not, but I also felt no need to negotiate with her the terms on which we did this. I go to weddings, baptisms, bar/bat mitzvahs. I don’t need to fight with people about those things. Nobody needs to fight about those things. But when ideas from these sources get connected to fights about women’s rights, to fights about racial injustice, and so on, then maybe we do have to knuckle down and see if we can’t sort it out. Maybe we do have to face the banal fact that everybody has a brain full of imperfect pictures, and so we better live in a world that recognizes this both as a positive and at times a deeply troubling part of our lives. It doesn’t always help to try and put together two incompatible pictures, even though each of them may be useful in some different context.

Again I sense As If’s understated dedication to your students (“idealizers and idealists”) pointing suggestively towards present-day conversational and interrogative parameters and possibilities. I find quite resonant, even if a bit dispiriting, your quick intriguing formulation that “The history of our collective moral learning doesn’t start with the growing acceptance of a picture of an ideal society. It starts with the rejection of some current actual practice or structure, which we come to see as wrong.” I would happily hear you out on if/how we might overcome or at least more productively manage the intersubjective constraint that “once we recognize that a belief is a priori false, we have a hard time figuring out what someone who had that belief should do.” So we could discuss the particularly generative appeal, both in Vaihinger’s work and your own, to a principle of promiscuous connectivity, to a self-propulsive spread across any number of fields in order to track and perhaps further extend “as if” propensities. Or more pointedly, we could detail what you consider some of the most compelling cases in which, say, progressive intellectual/artistic/political circles most strikingly fail at present to realize the potentially helpful aspects of seemingly opposed (perhaps empirically unsound, perhaps internally inconsistent, yet nonetheless useful) perspectives or practices. But in any case, since your own book operates in the “as if” from the start, framing its inquiry through the opening phrase “Imagine that,” could you take us to some of the most far-reaching applications and further-pushing vistas you would like to see “as if” thought processes traveling towards?

Ah, people always ask philosophers to be prophets! If I knew where the next new useful “as ifs” were, I’d be pursuing them already. But the most useful thing I can say here looking forward, I think, is just that we all need to be more open to our own fallibility, recognizing that our very best attempts at understanding are going to be imperfect, and that what matters is that our pictures should serve the purposes we can make sense of now. Of course those purposes are different in different people, and at different moments. And sometimes our reason for rejecting a picture can be that it is being used for purposes we abhor. Then we will want to put pressure on it, raise arguments against it, look carefully at the evidence it claims. Our cognitive imperfections live alongside our sentimental imperfections — our tendency to partiality, to special pleading and the like. It’s super hard, we should admit, to adjust to the understanding that we manage our world only through idealizations. But, at least sometimes, it can help.