While in Perth, Australia for the Perth Writers Week, Ben Okri and I caught up over a lunch of spatchcock and fresh tomatoes. We talked about local honey, racism at customs, and the distance between generations. This was, of course, in addition to poetry, truth, and aesthetics.

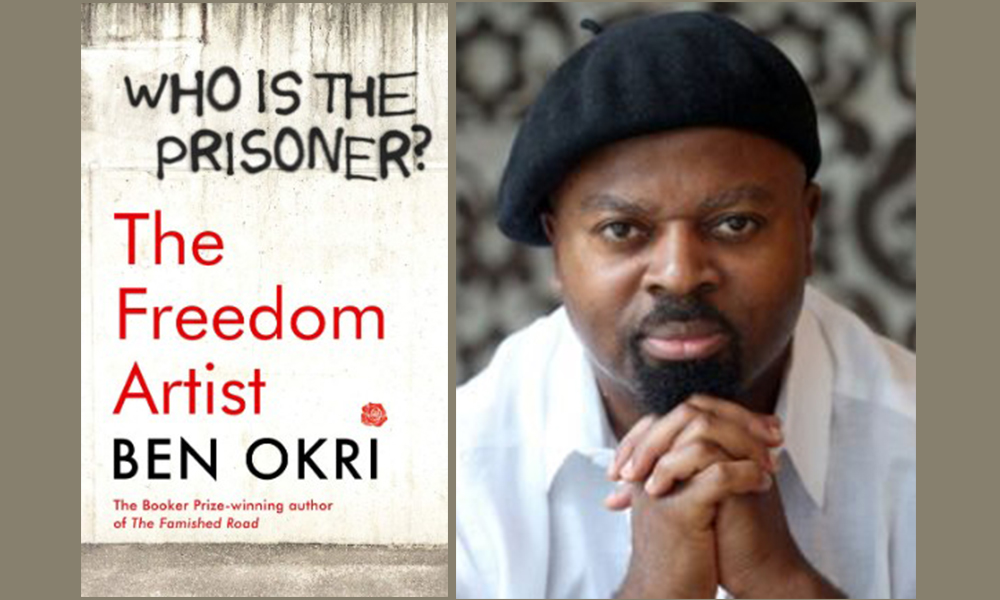

Okri grew up in Nigeria before moving to the United Kingdom. He is a widely respected poet and the author of The Famished Road, which won the 1991 Man Booker Prize. Okri has also been awarded numerous prestigious international prizes and holds honorary doctorates.

¤

ROBERT WOOD: How did you become interested in poetry and writing? What was your initial desire to become a poet? Did you choose it or did it choose you?

BEN OKRI: That’s a hard question to answer. I think there are many pre-existences before the hunger for aesthetics and truth takes hold of the spirit in the form of narrative or poetry. If I was to speak of what turned it in me, I would have to put it down to the Civil War. The Civil War was about language, about voices, about fractures, about broken unity inside another broken unity. It was also the moment when I became first aware of myself as a being on whom conflicting narratives were written. The Civil War divided my sense of life between a time when life had a wonderful unity and an awareness of death. This is before the incident of nearly being shot. It was around the time when I saw my first corpses of young students. They had been shot and dumped in the river. It was a time when some neighbors turned against us and my mother had to suddenly go underground. The whole thing about voices, the perilous nature of language, become apparent to me. When I first came back from England, when I first returned to Nigeria, there were voices and languages, registers of voices, a new anger. You knew there was something wrong even before the war broke out. People didn’t talk; they shouted at one another. There was a new intensity to the way voices clashed. Dissension voices that echoed through the communities.

In cultivating your own voice you have spoken about opening the novel up to a new poetic voice. This has been an interest since your editing of West Africa. Where you writing back to that yet, or, was this about coming to understand your own voice?

I was still a child then. What I want to say about voices is that there were other voices — that of my mother and her storytelling, the gradually fading voices of the elders in the community, of poets who satirized, celebrated, and observed. But those voices couldn’t be heard. They were marginalized by war voices. I think when you are surrounded by many voices and in the case of Nigeria over a 100 languages, there is a sense in which the individual either surrenders to the dominant voice of their community or they start asking questions. Asking questions is the beginning of finding a voice.

This question of voice is interesting. There is a sense of polyphony and the multiplicity of voices you inhabit. Can you speak about voice as a many-sided, many-timbered understanding of the world?

In this inter-lingual universe, we often tend to speak of voice as one thing, one register, one tone. I like that you bring polyphony to the idea of voice. A voice always has so many layers. There is the combined aesthetics of what you inherited. There is the aesthetics that you have shaped. Then there is the historical layer of the times in which you find yourself. All of these are there, in any given voice that is achieved. I am thinking of what Yeats calls “his many masks” and the masks of voices. I am thinking of Okigbo’s Egungun voices. There are the multiple sides of the voice. When a voice faces the community, it is inflected in a certain way. When it faces the ancestors, it is inflected in another way. It really depends on the dialogue you are having, the ritual context you are in.

Leading from voice, I have a question about language. As you spoke I was reminded of Achebe and Thiong’o’s debate about English in Africa, where Achebe wrote in English and Thiong’o wrote in Gikuyu. Hearing you speak about Nigeria and the multiplicities within multiplicities, can you comment on the relationship of voice to languages.

I am tempted to say that what you are saying works both ways. The Africanization of English, but also the Anglicization of Gikuyu. We don’t talk about this, but to what degree was Ngugi [wa Thiong’o]’s writing in Gikuyu inflected by his submersion in the English language? The transaction is the two-way thing. We try to give the impression that there is a wall between languages when in fact there is a constant dialogue, a subterranean leakage. And so for me, language is never pure, in the sense that it is divorced, that is separated from the under-stream that informs its usage. For me, language is informed by my father’s people, my mother’s people, the composite aesthetic sense of being a Nigerian, even of being an African, alongside a South London upbringing and subsequent years in England. It is all in there. So the dialogue between Achebe and Ngugi was too polarized. There are many spaces in the middle where they leak into one another, where they inform one another.

I think partly what you are saying is your comment on how language exists in the real world, but also about code switching and translation. And translation helps me think through your work from imagination to reality and in between. This calls to mind dream logic and returning to a community.

The dream logic is something I discovered. It came from my fascination with the fact that life is not as linear as we think it is. The linearity of life only exists when you remove consciousness from the picture, which is impossible. As soon as you put consciousness in there, the narrative becomes unworkable, a fantasy, if for no other reason than we are constantly invaded by a sense of the future, constantly altered by streams of the past that haven’t arrived yet. Consciousness is constantly flickering between all of these territories. So how can we speak of linearity, when you have all these time breakages that are part of consciousness itself?

When you say dream logic is a discovery for you, is it a point of origin where you depart from, that you compose from?

The bringing it back itself has to be qualified by a conscious aesthetic application. It cannot be a pure bringing back from dream.

Tell me about the bringing it back. What is the aesthetic application in a conscious way?

It is difficult to express this, but the conscious bringing back is a part bringing back, a part glimpsing, a part making, a part shaping, a part listening, and then a part uncovering. All of these practices are what we can call the ongoing progress of a work of art — an essay, a poem, a short story.

This brings me to your latest work, The Freedom Artist. Tell us about it.

I will speak obliquely because if I speak obliquely I will speak more clearly. It is a story and a poem and a dream and a nightmare, a fear and a hope, an alchemy and a spell and a liberation. I have been wanting to write this book for thirty years, maybe even longer, for many different reason. The initial reason was something I glimpsed about the human condition, something about us, about the perceived freedom of our state, which is an illusion, and I perceived this even before the war. But that got qualified. Society is a circle of prisons that we inhabit and which inhabit us. The prisons could be policies, perceptions, cultural mores, state sanctioned ideas of the human, class, gender, race, religion, etc. But a book can only be written when the essence of the book is in tune with or resonates with the moment we live in. Something about the air suddenly made this book right to compose. Something about freedom being threatened, the distortion of truth, something about the violence that has been inflicted on “the human” and the way that violence has been normalized by politics, the normalization of profound violence against the human. I am not only talking about blacks, gays, women. But something fundamental about the human is undergoing a deep compression. Certain things you could talk about ten years ago, that you cannot talk about now. The novel has come out of that, a toxic air.

What do you think the deep compression is? What can’t we talk about now?

Many things. The more relevant question is what has been normalized that allows such great violence against us. What has been normalized is the idea that the humanity of some people is structurally and fundamentally less than the humanity of other people. The fact that this has been normalized ought to be a trauma for us. We are living with deep fracture.

What do you see the role of the novelist and the poet and the dreamer in that deep fracture?

The roles are manifold and self-chosen. Poets and dreamers can function any way they see fit. For me, it is to draw the collective ear of humanity to the howl in that fracture. Because where there is a fracture there is a howl. But we are not hearing it. I think part of our job is to magnify the unheard scream that is in the fracture. The scream is not only the scream of the wounded. It is all of our screams. You cannot wound somebody without wounding yourself. We are all screaming.

This goes back to dialogues, to polyphony, to bringing things back from dream.

Bringing things back to a reality that we are not facing. There is an aspect of reality that is a dream in the sense that it is unreal to us. Dream for me has many meanings. There is a dream that is a source, a resource; a dream that is a homeland of the psyche. There is another dream, which is the dream of the world that is asleep. The word dream is like the word voice. It has many faces. The Freedom Artist is about the many faces of this dream, this nightmare.

And to give voice to a dream that might be real for fellow travelers. Can you speak about community in that way, in terms of responsibility, but also what it is to travel to the other side of the world and how we encounter strangers?

What is it to encounter strangers, what it is to be a stranger, is at the root of everything that we are talking about, is at the root of this world we find ourselves in, the world that we have created, at the root of this nightmare, at the root of this hope. The story of colonialism is the story of strangers violating their hosts. It is the story of The Odyssey and The Iliad and Things Fall Apart and Death and the King’s Horseman. When you think about it, it all comes down to deeply abused hospitality. In 1413, the Portuguese land in Africa on their way around to South America, looking for gold. They stop off in Africa. They hear about this gold that can be found. They start off being welcome strangers, and we know what happened after that. It began a deep fracture, a deep wounding of the continent; that continued for five, six hundred years. It began with a story of strangers and hosts. Fast forward five or six hundred years, what is the discourse in the western world, at the heart of Brexit, Trump’s wall? Migrancy, immigration, strangers, it is the same thing. That is the same simple thing running through the history of different civilizations that have encountered one another in violence and abuse.

When you ask me about the relationship between poetics and community, I would say that poetry is really about creating the highest kind of community. Poetry is about sustaining the highest kind of community. Poetry is about passing on the richness, the validity, the truth, the ancestral wisdom of a community, whatever that community is. But poetry is not only about giving, about passing on, about composing and imposing. It is also about receiving in the listening. Because that is at the basis of community. We have a saying back home, when a storyteller gets up to tell a story, he says, “I have come to tell you a story, have you come to hear it?” The one cannot exist without the other. The community prepares itself for listening. The community creates itself by listening.

And this is where we no longer become strangers.

I think poetry is the strangest thing. Poetry is an outsider and an insider thing. Even in a community where the poet is central and secure, where he or she belongs to the land, and holds the treasures, the poet is still an outsider because they are operating from psychic and spiritual territories that are not entirely of this earth.

What is the role of poets now and into the future then?

I think the poet has to be braver with their humanity. The poet has to embrace the difficult questions that politicians are not prepared to ask anymore. I feel, and it is a risky thing I am about to suggest, that we have allowed the politician to usurp the central territory of the poet, which is dream speaking to dream, high truth to high truth. I think the poet has stepped back a bit too much, has left a certain territory of public discourse to people who abuse strangers. All of us are wanderers through the earth. We ought to awaken in one another both a sense of our temporality here and a sense of eternity in one another. But there is this way people have of dividing humanity, creating a sense of them and us, home and stranger. But our world has to co-mingle. Our fates are too linked. We have done enough poisoning of one another’s destiny. We need to bring something of the healer back. We need a poetics of healing. I am not only talking about bandages, but about the depths of language and the heart. Perhaps even a revolution in our idea of what it means to be human. Words in their highest configuration can re-align us in magical new ways. I have always dreamed of a new aesthetics that counteracts the poison of our times. An aesthetic that is also a high act of politics. Or a politics that is also a high act of aesthetics. Politics is too important to be left to politicians. We need to cast new spells for the future.