Leïla Slimani’s second novel, Chanson Douce, was awarded the 2016 Prix Goncourt in France, and was recently published in English as The Perfect Nanny. The story of a bourgeois Parisian family who hires a nanny so that the mother, Myriam, can go back to work, The Perfect Nanny begins at the end. We know from the start that the children will die and that the nanny, Louise, will be the one who kills them. What follows is my favorite kind of novel: a book where you want to linger over every sentence, but the sentences have a propulsive energy that won’t let you. I wanted to linger, reading The Perfect Nanny, because these sentences are precise, direct, and imagistic in their revelation of unsettling truths about bourgeois domestic life. I pressed on, though, because I wanted to know how it would happen that these truths — which felt like they could be my own secrets, or the secrets of half the families I know — doom this family in particular. We are, in fact, all doomed. This novel feels ancient as well as scarily contemporary: it makes the myth-like move of rendering literally, as action, a danger that’s real, but that usually lurks more quietly. Daphne is literally rooted to the ground, fleeing a man; Narcissus literally wastes away due to vanity; and the Massé children literally die at the invisible collision point of egotism and eros, race, gender, and class, where most contemporary, upper-middle-class, urban families raise their children.

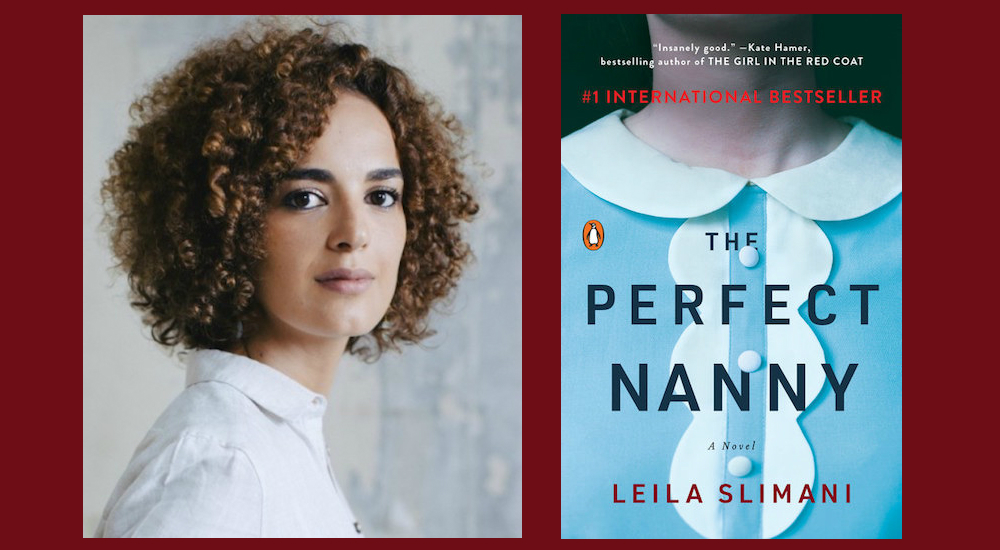

Slimani and I spoke at the Last Bookstore, when she visited Los Angeles in April on a book tour.

¤

REBECCA SCHULTZ: The inspiration for this novel was the murder of the Krim children on the Upper West Side in New York. What so interested you in that story?

LEÏLA SLIMANI: Actually, that was not the inspiration of the book. I was already writing the book when I discovered the case in New York. My idea, at first, was just to write a book about a nanny. A nanny is an interesting character for a novelist. She lives in a family where everyone acts as if she was a member of the family but everyone knows she’s not. She lives in a house and everyone tells her it’s her house, but everyone knows it’s not. And she raises children who are not her children. So she’s always in an ambiguous position. She shares the intimacy of a family but at the same time she’s always a stranger. I was raised by a nanny myself, in Morocco. She was like a mother to me, but I remember that even when I was seven or eight I knew that her position in the house was weird. I could feel that she was living in our home but that our home was not hers. I could feel that she was sad, that she was humiliated. I understood that there was a gap growing between her and me, because she couldn’t read and write, and I was learning to read and write at school.

And then I became a mother myself. I was working as a journalist and I needed a nanny to take care of my son, so I decided, like many Parisian parents, to do interviews with nannies. It was in the afternoon, in Paris, and many women came to our house. I was 30, I was mother to a little baby, and I felt like a baby myself. I knew nothing about life, and I met women coming from the Ivory Coast, women from the Philippines, women who were mothers themselves. They had to leave the children in their country. I felt it was strange that I was going to be the boss of one of these women. So I wanted to explore this uncomfortable position that I was in, and that the nanny is in.

So that was the idea. But when I started to write, I discovered quickly that my book was boring, because the life of a nanny is boring. It’s repetitive. It’s trivial. I wrote one chapter about her cooking, another about her going to the park. It was like, okay…and now what am I going to write? I needed something to put narrative tension in the book, and to help the reader want to turn the pages. I needed the reader to be active in this book. And when I discovered the New York case, I had the idea of beginning with a murder. I wanted to face the violence that exists in this relationship — a violence that’s invisible, because you don’t want to look at it. You don’t want even to think about it, when you are a mother or a father who hires a nanny. So it unlocked my inspiration. It helped me structure the book.

You have a line at the beginning, about Myriam, the mother: “She had always refused the idea that her children could be an impediment to her success, to her freedom.” It would be a simplistic, moralistic reading to say that the novel wants to punish her for wanting to be free in that way — that this invisible violence is her and her husband’s fault. Nonetheless, Myriam and Paul are engaged in some dangerous hypocrisies.

I never judge my characters. I became a writer because I hate judging people and I hate feeling that people are judging me. When you are alone in your apartment — your children at school, your husband working — and you begin to write, you feel so free, because you can construct another world, and you can try just to understand another human being. You can stop judging him — stop saying he’s good, he’s bad, he’s like this, he’s like that. We never know other people. We know the surface. We can understand some things, but we don’t know who a person is. We know just little things — the rest is a mystery. As a writer, I like to explore this mystery. I’m not here to solve the problem. I’m not here to say, “Myriam is this,” or “Louise is that,” because I don’t know. Concerning the hypocrisies, I think that the main one is in the relationship between Myriam and Louise. Like many mothers, Myriam wants her children to love the nanny. She feels less guilty if her children love the nanny. But she doesn’t want to love her too much, because she is the mother.

The other strange thing about this relationship is that you are entrusting your children — what you cherish most in the world — to someone that you absolutely don’t know. I remember the first time that I left my house after saying goodbye to the nanny and to my son. I closed the door and I thought: this is weird. I don’t know this woman at all, and I’m leaving my son with her. You can’t understand the rationality of your decision, but you have to do it, or you can’t go outside to work.

And of course, when you’re dealing with intimacy between strangers, there’s going to be mutual projection, even fantasy. Louise is an asexual figure, to Myriam and Paul. She’s doll-like, child-like. And yet she wants something more from them: some of their intimacy. With other nannies — or, governesses, I guess — in literature, too, there’s this simultaneous spookiness and sexiness that comes with occupying this position in a family. I’m thinking of Jane Eyre, or The Turn of the Screw.

Yeah, you’re right it’s spooky. I remember I spoke with a nanny, and she said I know that my boss is an alcoholic. I know where she hides the bottles. I know everything about her. I remember when I told my sister I was writing a book about a nanny, she said, you know what’s weird, my nanny knows when I have my period. It’s the most intimate thing that you can imagine. But she’s a stranger. So, of course it’s spooky. It’s sexy, potentially, for the same reason. But then, Louise is a perfect nanny because she is child-like and doll-like. Those qualities make her invisible. She belongs to the world of children, and that’s why she’s perfect. I heard a lot of parents who told me that a perfect nanny is a nanny that you don’t see: that won’t make you feel uncomfortable when you go back home, because you don’t see her — she’s with the children.

Which goes right into the heart of the violence here: that need to not see someone, to not relate to someone who makes your home function. Early on in the novel, we learn that Myriam “does not want to hire a North African to look after her children.” How does Myriam’s race affect her relationship with her nanny, and with her bourgeois world more largely? Similarly: how does Louise’s whiteness affect her identity: the way she sees and is seen? It strikes me that whiteness is dangerously implicit in the very concept of “the perfect nanny.”

You know, I don’t think about identity in my books, because obviously think that’s what I’m going to write. I don’t care about identity, I don’t really understand what it means. I’m not interested in what people are; I’m interested in what people do. So in my books I like to make plenty of references to identity, and often with an ironic tone, just to say that maybe identity is not the clue, and it can’t help the reader understand the character. But Myriam, she is probably from North Africa — we don’t really know where she comes from. And she doesn’t want to hire a North African nanny, because she doesn’t want to have this sort of complicity with her. She doesn’t want the nanny to speak with her in Arabic, and to speak with her about religion, and then to think that they suddenly belong to the same family, the same group. She wants to avoid this immigrant solidarity. For her it’s a way to put up boundaries, and to avoid any proximity. She thinks that being a good boss, a good employer, is to be somebody who is going to keep this boundary. But of course she will discover that’s impossible.

Literature is there to tell us that reality is much more complex than what we usually read or see on the media. Of course, when you think of a rich couple with a nanny, you think that the rich couple is white and that the nanny is from North Africa or from the Philippines. But I thought it was more interesting to say that today, in our society, some immigrants are rich, and they hire a nanny, and that some white people are poor. Louise is doing an immigrant job. Her husband is always making fun of her for doing an immigrant job. It’s demeaning for her. It was a way for me to emphasize her humiliation, and also her loneliness. When she goes to the park, she’s the only white nanny. She doesn’t belong to the group of African nannies, or Asian nannies. She’s sort of an anomaly. It’s important to the characterization of Louise, that she is someone who doesn’t belong. She doesn’t belong to the family, she doesn’t belong to the world of nannies. And she desperately wants to belong.

And her status as a white nanny is also what makes it so easy to project onto her, in some ways. She’s described as a Mary Poppins figure at one point. She seems to come from this old-world idea of a nanny. But then of course, the family’s wanting to see her that way is part of the violence here.

What about Paul? You describe his buoyancy. There’s a certain joyful entitlement to the way he takes up space in a room. Of course, he doesn’t have the same “impediments to his freedom” that the world would put on Myriam.

Paul is cool. He’s sort of a hipster — what we call in France “les bobos”: bourgeois-bohème. They eat quinoa, they ride bikes, they drink green juice, they go with their children to the park. He’s also new generation of father who wants to be involved in raising their children. They play with them, they spend time with them. But at the same time he wants to be free and he’s afraid of losing his freedom because of his children. He’s afraid that the fact of being a father is going to make him get old quicker. He wants to stay young and he wants to stay cool. And he thinks in a certain way that he can have it all. Myriam, by contrast, feels she’s sure that she can’t have it all. She always feels guilty about something: when she’s at work she feels guilty for not being with her children, and vice versa; but Paul, he’s cool and he’s confident. He says to Myriam: we’re going to do it. We can be good parents and go out at night, and hear music, and we can be wild. We’re not old. He’s optimistic.

He also doesn’t get involved in the relationship between Myriam and Louise. When I began to write this book, I talked with friends, and I read books about nannies, and I discovered that men don’t really get involved in the relationship with the nanny, except when there are problems, or on the day where they decide to fire the nanny. In 90% of cases, it’s the man who fires the nanny. And in 90% of cases it’s the woman who hires the nanny. The woman is the one who decides who is going to play the role of the mother. But the father is the one who severs the relationship: who says, we’re not going to pay you anymore and you have to leave.