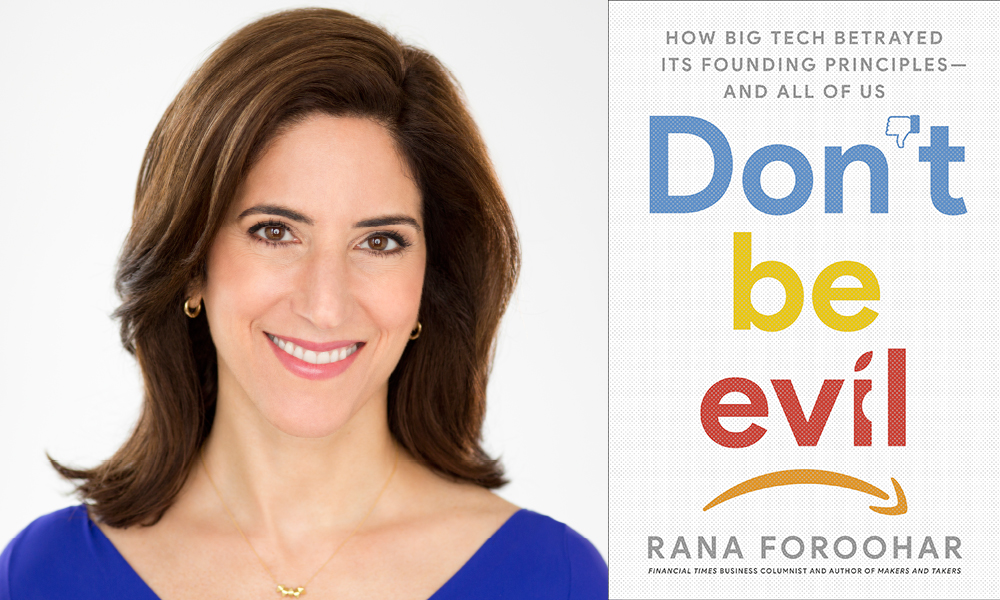

How might Google’s present-day mode of profit making fulfill its own founders’ late-90s fears of insidious advertising-funded search engines? How might Amazon’s multi-layered market dominance most resemble that of 19th-century railroad robber barons? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Rana Foroohar. This present conversation focuses on Foroohar’s book Don’t Be Evil: How Big Tech Betrayed Its Founding Principles—and All of Us. Foroohar is global business columnist and associate editor for the Financial Times, and CNN’s global economic analyst. Her previous book, Makers and Takers: How Wall Street Destroyed Main Street, was shortlisted for the FT/McKinsey Business Book of the Year award. For her technology and policy writing, Foroohar was named best large-publication columnist of 2019 by the Society of American Business Editors and Writers. She is also the 2019 winner of the Arthur Ross Award, given by the American Academy of Diplomacy for foreign-affairs writing.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Today we all might recognize the ways in which making information and media “free” online perhaps most benefits not content creators or consumers, but tech platforms — allowing them to attract users, harvest user data, and generate micro-targeted ad-driven revenue. But even in Don’t Be Evil’s meticulous account, it sometimes gets hard to pinpoint precisely when Google begins to grasp just how profitable its pioneering mode of surveillance capitalism eventually will become. So to start, could you walk us through Google coming to realize the theoretical/technological implications, the commercial applications, and the legal/political ramifications that ultimately prompt your own book to explore how this firm “evolved from the scrappy, cheerful, and idealistic enterprise of its early years to the vast and more ethically questionable corporate entity it is today”?

RANA FOROOHAR: In a way, that question covers the whole scope of this book. We need that whole span of more than 20 years to ask: how does Silicon Valley go from being this kind of utopia (an idyllic space for kids in garages to come up with great new innovations), to today’s dystopia? I’d start that story in the mid-90s, and probably pinpoint, as the first big shift, when Google’s founders Larry Page and Sergey Brin wrote (as Stanford students) their famous first paper on search. And I just called this paper “famous,” but it actually shocks me that you don’t see more people discussing its implications.

This 1998 paper basically sketches out Google as we know it today. It gives a detailed preview of how Google’s large-scale search engine will operate. It outlines how you make that search engine, and how it functions. But if you read all the way to the very, very end of the paper, you reach an appendix. This appendix discusses advertising, and the problems with advertising as a business model to support a search engine. Page and Brin actually say quite openly: “We expect that advertising funded search engines will be inherently biased towards the advertisers and away from the needs of consumers. Since it is very difficult even for experts to evaluate search engines, search engine bias is particularly insidious.” They predict this whole possible misuse by companies or other entities. Then they even go on to say that, because of these dangers, it might be in the public interest to design some kind of open or academic or nonprofit-type search engine, so that we can avoid these problems.

So at that point, in the 90s, we still have this kind of idealism. Most people building the Internet back then, including the Google founders, were these utopian types who wanted to connect the world by putting all of its information online. But the broader possibility for negative ramifications, in some cases ramifications that might outweigh the positive — I just don’t think that entered their minds. And we should remember that these folks, who tend towards the socially liberal side, also have this libertarian streak. They certainly believe in unfettered capitalism. They likewise believe in the ability of companies (particularly high-minded digital companies) to fly 35 thousand feet above the problems of the nation-state.

You can see this right now in the public battle between Mark Zuckerberg and Elizabeth Warren. To me, that represents this much bigger battle between the apex of neoliberalism and globalization as we’ve known them, and some new kind of politics in which we get (guess what) concerns about the nation, concerns about everyday American citizens and American voters. And of course these companies crossing borders and doing whatever they like, and offshoring taxes to wherever they want, might someday soon have to face up to the fact that so many of their most profitable innovations come directly out of taxpayer-funded research and development of the Internet, of GPS, of touchscreen technology — but without having that resulting wealth enrich the larger ecosystem. Instead it just enriches a handful of companies.

On a parallel historical timeline, could we also start tracing the original ideals, and then the more crass contemporary practice, of Stanford Persuasive Technology Lab-inspired “captology”: with Facebook “likes,” for example, flattering us and simultaneously training us to become Pavlovian dogs, with multi-sensory smartphone notifications evoking our own portable slot machines, with our resulting attachments to intermittent variable rewards leaving us obsessed, stressed, anxious, sick?

Right, just today, on the subway, in every direction I turned, literally no one was looking up from their phones. Our entire interactions in public spaces have changed. That, I would say, really began coming about around 2007. First, in the early 2000s, this field of captology started getting further developed at Stanford. And that brought together all of these various persuasion strategies — some of them just old-fashioned casino gaming techniques, and others more cutting-edge behavioral-psychology scientific findings. We’d had of course those 20th-century experiments with dogs salivating from clicker sounds and that sort of thing. But when the smartphone really reached the market in 2007, then everybody was off to the races.

By now, that entire scientific and psychological and technological field of persuasion has been elegantly compressed into this little device literally in your hands most of the day. Suddenly, you’ve got a slot machine in your pocket. That all adds up to us finding ourselves so glued (in some cases addicted) to our phones.

Well your book makes its basic moral case in part by quoting psychologist Richard Freed’s account of an alliance pairing “the consumer tech industry’s immense wealth with the most sophisticated psychological research, making it possible to develop social media, video games, and phones with drug-like powers to seduce young users.” And your book makes its basic economic case by demonstrating that “the tech industry provides the starkest illustration of the rise in monopolistic power in the world today,” with Big Tech firms routinely stealing smaller companies’ intellectual property, shaping a legal/political regime that disproportionally allocates marketplace protections to dominant incumbents, stifling a subsequent generation of job-creating firms. I’ll want to ask more detailed questions both about that moral critique and that economic critique of market concentration. But first, could you describe the thinking that prompted you to bring together in this book such a vast inventory of today’s tech-driven social disruptions? “Individually,” you tell us, “each item is just a speck in the eye, but collectively it makes for a sleet storm, a freezing whiteout that yields a foggy numbness, the anxious haze of the modern age.” How did you come to realize that this book would in fact have to drive right into the center of that sleet storm if it ever hoped to gain traction?

I definitely had this kind of dual-strand moment of awakening. Three years ago, I started a new job as chief business columnist at the Financial Times. I had the mandate to look at the world’s most important economic and business stories, and do op-ed commentary on them. And whenever I take on a new assignment like that, I start off by following the money. I try to find out who has the money and the power. As I began digging into these questions, basically for the first time since the 2008 financial crisis, I just couldn’t believe the huge migration of wealth and power over that decade to the tech sector. For just one of many shocking statistics, I found a McKinsey figure showing that about 80 percent of all corporate wealth now lives in just 10 percent of (very data- and IP-rich) companies — with the richest of course the big platform firms (Google, Facebook, Apple, Amazon), the big banks, and some other tech firms like Cisco and Qualcomm.

And then, even as I researched these broader trends, something was happening on a very personal front in my living room. I came home one day and opened a credit-card bill, and noticed all these charges of $1.99 or $3 or $5. Of course I thought: Oh god, I’ve been hacked. I’d just been traveling. I assumed somebody had my credit-card number. But then I saw that all these charges came from the App Store. And it suddenly occurred to me who else had my password — my then 10-year-old son Alex. So I went downstairs, and found him of course sitting in the usual position on the couch with his phone. I tried to get his attention, which took a minute. Finally he put the phone down. We turned it off so it would stop beeping. And I more or less started to interview him. He knows not to use my password without asking. But it turned out he had gotten completely hooked into this online soccer game.

Often you get these games for free. But of course, as with something like Fortnite, the game’s maker earns the vast majority of its money by selling you things while you play the game. As you play, the game offers different things you can buy. Particularly from a child’s perspective, this particular marketing strategy works in such insidious ways. You almost don’t notice yourself buying new stuff. You just get pulled along by these persuasive nudges. These captology techniques keep coming — engineered to keep you playing, to keep you online. And all the while, various applications track your movements in the game, as well as your physical actions, and harvest that data, which they then sell to advertisers, or use to sell you more stuff inside the game. All of this of course horrified me as a mother. But it fascinated me as a journalist. I sensed this whole new industry about to eat everybody’s lunch. I realized I needed to understand every single thing about it.

And alongside that depth of capturing individual users’ attention, tech platforms of course have (and need) enormous breadth. Don’t Be Evil makes the point that household-name Big Tech firms are firms that (again often through quite concentrated, top-down management structures) prioritized and then succeeded at tapping network effects, growing exponentially, becoming dominant incumbents with all of the self-reinforcing benefits of that status. So here again can we take Google as our model? And could we, for clarifying contrast, compare Sun Microsystems’s late-20th-century embrace of an open-source ethos (celebrated by economists for catalyzing innovation and broader economic growth — albeit with less potential for patent-protected profits) to Google’s slightly different approach of pursuing maximum accessibility, but while still remaining protected just enough to “begin using their power to reshape the innovation ecosystem to fit their own strategic goals”?

So to return to our historical timeline, we’ve now had this amazing search engine developed. Google has become a company. They’ve started heading slowly but surely towards what every investor wants, a big IPO. Now when you start approaching the IPO, you actually have to make money. You need a persuasive model for how you will do that. So now folks like Eric Schmidt (Google’s former chair and CEO) start coming in. Eric had been at Sun. He was an industry veteran, and Sun did have this open-source model.

Historically, certain parts of the tech sector, say the biotech sector, had depended on the patent system. And historically, technology innovations were more discrete. They were often these singular new ideas an inventor would develop and then patent. But as we began shifting from the semiconductor industry to software to the Internet, things got a lot more complex. A big company like Google or Apple runs on lots of different technologies, in your smartphone for example. So some of these companies actually don’t want a strong patent system. They want more of an open-source approach. They also want to grab as much market share as possible, so that they can start benefitting from the network effect (with so many people now in their network that the switching costs for individual users gets very, very high). So Google eventually becomes our de facto search engine, even if they still say: “Well, competition is just a click away.” Sure. But I mean, if your Google goes down, you probably take a walk around the block, drink some coffee, then check back in — rather than use Bing.

Then on the legal front, the book refers to this source I found who interviewed for a Google lobbying job in the early 2000s. By then, Google clearly had started to think through how it needed to keep data as free as possible, to reduce regulation, to reshape the patent system to favor its own business model (rather than that of discrete inventors), all to ensure that Google could keep control of its whole ecosystem. So in 2019, when Big Tech executives give Congressional testimony on the Hill, when they say, “We couldn’t possibly have imagined where we’d be today,” we all should hear that as complete and utter BS. If you look at the documents, if you look at the meetings taking place, you see them gearing up for this whole shift over a decade ago.

For one specific example of Big Tech social disruption, could we look back at the closing of over two thousand local US newspapers (with TV stations probably next to go) since the rise of Google and Facebook, and could you describe what you find most problematic in the behavior (not just the impact) of these firms? Should our news media, for example, never have relied so heavily on ad-driven revenue in the first place? Should we see nothing wrong with tech firms responding to significant inefficiencies in 20th-century mass-marketing? Should we only consider these firms at fault when, say after having revolutionized data-mining, they still claim to lack the capacity to regulate their own platforms — or when, after starting to invest substantially in content creation, they still hide behind Communications Decency Act protections while distributing (whether or not “publishing”) corrosive, distorted, deceptive, potentially libelous content on a global scale? When (and in what specific moral or economic terms) does the “Don’t be evil” credo no longer apply?

I think Google really starts tossing that all out the window prior to its IPO. Again, the Googlers themselves initially describe the mining of personal data for targeted advertising as immoral. But the venture capitalists eventually push them towards this obviously quite profitable model, and eventually Google itself says: “Okay. You know what? Maybe being a little evil isn’t so bad.”

But then for the news business, first I’d point to journalists sometimes getting slammed by people who say: “Oh, that’s just navel-gazing to obsess over this one story.” Actually, I consider this a really important story for everybody. I consider us the canary in the coal mine, showing what will happen basically to every business, if we don’t improve our regulation of Big Tech. Let me walk you through why. First, the news companies obviously did something unwise when they declined to demand getting paid fairly for their content. Again my book follows how Google just comes in, doesn’t ask anyone, and starts reprinting all of the world’s books on its website — with this kind of mind-boggling disregard for copyright. That showcases this whole move-fast-and-break-things model in which we don’t care about other players in the ecosystem, in which we don’t think about the broader impact on society. We just do what we want and then ask questions or pay fines later.

Jonathan Taplin wrote a book about how this plays out, for instance, through the lens of the music and entertainment industries. And pretty soon, the Big Tech guys come to the media (especially the news-media) firms, and say: “You don’t understand this new economy. Information wants to be free. You need to put everything out there. We’ll help you monetize it.” Well, guess what? They took over most of the advertising pie for the entire print-media industry. They’re on the way to doing the same with television, which I expect will fall off a cliff (in terms of revenue) and will get disintermediated even faster than newspapers and magazines, because TV actually has less content of value to sell.

You also mentioned Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act, for which the tech industry lobbied very hard. CDA 230 might sound wonky, but it still has this hugely important impact. It still gets pushed through in all of our new trade deals, like the new NAFTA. Lobbyists still work extremely hard on this in Washington, because it gives these tech firms no liability for anything said or done on their websites. They can develop this huge distribution scale that The Financial Times or The New York Times never could achieve. And all the while, they face no liability. I mean, if I write one or two inaccurate words about someone, The Financial Times gets a call. We could face a defamation suit. Facebook, meanwhile, can help videos of graphic murders and mass shootings go viral, and can actually monetize these videos with no liability. Facebook can become the largest forum for child pornography, with no liability. So first off, we see these horrific moral issues involved. But we also see this fundamentally unequal playing field. These companies don’t have to abide by the same regulations as the media businesses, even though they’ve become a media business, even though they’ve become an advertising business. I sense this all about to change, though. We already hear ambitious calls for a new regulatory framework.

Along somewhat similar lines, could you make your case that Big Tech’s ongoing fight for “net neutrality” does not really present some noble defense of the public commons, so much as a turf battle against telecom providers — and with these telecom firms at times having a legitimate gripe, in terms of building out infrastructural capacities we rely on today, but without earning back corresponding profits? And could you bring in good-faith NGOs feeling incentivized and/or pressured to take Big Tech’s side in this dispute (along with House Democrats framing this as a progressive cause), and trace a broader pattern of public debates around the regulation of, say, self-driving cars (or surveillance, or antitrust, or copyright concerns) so often getting captured by Big Tech’s extravagantly funded PR power?

Sure. We can start with Big Tech becoming the largest corporate lobbying body in the country. We need to remember that, and net neutrality offers a fascinating case study. Today, “net neutrality” basically means everyone should have equal access to spread their message on the Internet highway, without having to pay tolls to jump ahead. As individual users, you and I likewise should have the same access to this Internet as anyone else, without rich people or corporations paying a fee to skip ahead of us. Everybody can agree on these basic principles of fairness, right? I mean, who advocates for creating new social or economic divides online?

But Silicon Valley has very cleverly taken up this issue to use in its war with the telecom firms. The tech firms don’t want to share the revenue pie more evenly. The telecom companies invested heavily in laying the broadband fiber that the Internet runs on. When broadband started to take off in the early and mid-2000s, Internet usage really, really picked up. Today, Big Tech companies can go on and ride that cable. Google and Netflix don’t have to pay any more to AT&T or Verizon for this high-density traffic, even with the tech firms earning high double-digit profit margins, and the telecoms earning low single-digit profit margins — and even after all the hard and expensive work of building out this infrastructure.

In other countries, you see different models. In China, the big tech companies have to participate much more in, say, building out rural broadband. That’s considered part of the quid pro quo. Alibaba (the Amazon of China) can make these huge profits. Jack Ma can become the wealthiest guy in China. But guess what? Alibaba will have to pay for some of this infrastructure building. I have a lot of sympathy for that model. I mean, I don’t often feel much empathy for Time Warner or AT&T. But I can’t help acknowledging how some of our tech companies conflated the call for individual freedom and equal access to this arrangement in which they can avoid paying their fair share.

Big Tech firms moving into media creation (or massive Google investments in self-driving cars, or Facebook’s initiative to create the Libra currency) likewise speak to Don’t Be Evil’s concerns about these firms not just dominating markets, but seizing markets. Here could you flesh out your comparison of Google’s and Amazon’s manifold operations (simultaneously as platform providers, and as competitors on these platforms) to 19th-century railroad robber barons? And could you point to near-future scenarios of Big Tech conglomerates managing an ever-larger share of everyday life amid an expanding Internet of Things?

It’s funny. My husband is actually writing a book about the 19th-century race to build railroads to the West. We kept coming back to these topics at the dinner table — with Gilded Era railroad barons operating just like Amazon today. I mean, the railroads did build their own lines. But then, by a certain point, they also owned all the cars on the lines. They owned big supplies of commodities (coal, various foodstuffs, grains) transferred on these lines. Eventually, they ended up with this encircling ecosystem, and could say to Coal Company X: “Alright, I’ll let you put your coal on my railway line, but it will cost 20-percent more to move your coal than to move mine, so I’m going to grab your entire industry.” Well, Amazon uses that exact model today.

To be clear, I could pick many different tech firms, but Amazon does provide this really good example. They’ve become the platform for e-commerce. Amazon already has this huge market. Commercial firms have to be on it. But Amazon still can, in a very opaque algorithmic way, put forward its own products. They’re even beginning to eat some of Google’s lunch, as they become a bigger place for people to start searches for buying products. When I searched the other day to buy my son some school supplies, whatever results came up first didn’t necessarily reflect what’s in my own personal interest. But it certainly reflected which products provide the highest profit margins for Amazon. And again, every time they do a transaction with any customer, Amazon garners this customer’s data, pulling in more and more information, which gives them more and more advantage in future transactions.

Pivoting then to antitrust conversations, could you begin tracing how Big Tech’s basic model of giving us things for “free” (again in pursuit of market share, lucrative user data, and subsequent incumbent clout) provides the almost perfect counterexample to antitrust frameworks single-mindedly focused on near-term consumer price-gouging? Could we maybe take Amazon’s current breadth of pursuits, and its long-term strategies for exploiting market dominance, as exemplifying Lina Khan’s critique of framing monopoly in an extremely narrow, linear, one-dimensional fashion? And could you start to sketch what it might mean to consider antitrust policy from a citizen-welfare perspective, instead of a consumer-welfare perspective?

Right, the young legal scholar Lina Khan has come out with this wonderful paper basically arguing: “Look. This is crazy. You cannot both own the network and own much of commerce that happens on it. That is, by definition, anti-competitive.” But this doesn’t actually count as anti-competitive in the courts’ current way of thinking about antitrust — which has this very Chicago School, Milton Friedman-esque bent. As long as prices stay down, our legal system sees no problem. But scholars at present keep coming in and saying: “Well actually, prices also dropped during the age of railroad monopolies.” We had to break up those monopolies not just because of pricing schemes, but because you can’t run an economy with a handful of companies owning everything. I see scholars like Khan (bringing in these new models of antitrust, and of power in the political economy) as becoming our moment’s Louis Brandeis, the famous reformer breaking up some of those Gilded Age monopolies. And if Elizabeth Warren becomes president, we very well might see a much broader rethinking of the entire dogma of antitrust law that has dominated the legal discussion for the past 50 years.

In the 1980s, for example, we had our previous major paradigm shift for the US economy. We stepped away from more state or public-sector control, to an economy in which privatization reshaped everything. Everything was about consumer welfare. As long as people kept paying lower prices, we assumed the economy was working great. And this overall economic shift included the rise of American multinational firms on the global stage, and these ideas that companies should locate jobs and capital wherever they want, and that Americans ultimately will benefit as we all keep moving up the value chain. It didn’t matter if we kept losing factory jobs, because we’d all become software engineers or bankers.

Well, when you then fast forward 40 years, you see quite clearly that we can’t have an economy that’s all PhDs and software engineers on one side, and all burger-flippers on the other. We actually do need something in between. But by this point we have directed so much of our attention to the consumer — and away from the citizen, away from the worker. And to close out these historical analogies: compared to the 2008 financial crisis, compared to how the big banks had grown too big to fail within that system, I’d argue that today’s Big Tech companies have become even more systemically important, and now represent an even more dangerously disproportionate percentage of the economic system.

Again, just look at how Amazon has grown. Today we shouldn’t think of Amazon as just an e-commerce platform. Amazon has become one of the largest logistics companies in the country. Amazon has become a crucial service provider for the federal government. Amazon has become a retailer, a food production and distribution company. There’s no industry you can’t imagine Jeff Bezos entering and disrupting overnight. And that’s all part of the plan. These companies want to become the operating system for your entire life. They now consider this their basic mission.

So returning to questions about market concentration and antitrust: yes, we buy stuff for cheap today. But incomes have stayed pretty stagnant in our broader economic ecosystem during these few firms’ rise over the past 20 years. Entrepreneurial zeal has gone down by many measures. The number of new startups getting seed funding has fallen. The number of companies successfully going public has fallen. We have four or five players cleaning up, with everybody else kind of running as fast as they can just to stay in place.

So amid these antitrust concerns, could you also point to some of the most troubling aspects not just of newly resurgent monopoly, but of monopsony — markets with only one buyer? Here I think of how labor-market monopsony further constricts the working lives of so many Americans today, both on a professional and industry-wide scale (with Big Tech-policed non-poaching agreements and broader “kill zones”), and on an economy-wide scale (in terms of all the displaced firms amid Big Tech’s rise). I also, of course, think more generally of precarious gig-economy employment, with Uber drivers classified as “entrepreneurs” largely left to fend for themselves, and with Starbucks’s supposedly compassionate labor-management approach still leaving baristas subject to inhumane scheduling algorithms.

Good question. I’ll start at the very top, then drill down to a micro-level. Again, at the headline level, think of how the Big Tech platform companies create far fewer jobs (relative to their market capital) than the previous generation of tech companies like Microsoft or IBM — and certainly far fewer jobs than mid-20th-century big industrials like GM and GE. So the nature of dominant companies’ labor models has fundamentally changed. Similarly, a budding line of research shows that today’s dominant firms generate far less economy-wide job growth than previous generations of firms. Companies operating in tangible industries used to need to hire developers and contractors to build factories. That required material suppliers, and that created all of these spinoff possibilities to increase income and job growth in the larger ecosystem. But today, if your company makes most of its money off patents, intellectual property, and data, that might create a few jobs, though not nearly as many. That creates very high-skilled, high-level positions for a few people living in communities with incredibly expensive real estate.

So of course we might remember the promise (certainly with the Trump administration’s tax cuts, but also for years before that) of how this Big Tech boom we can feel all around us soon will pay off, and will bring these huge new investments in our Main Street economies if we just get out of the way and let capitalism run its course. Well, not so much. It actually might not take much investment to develop a piece of software. And once you develop this software, you might devour whole industries — as we’ve seen with Uber.

And then your question points to how, when these players get so big, like an Apple or a Facebook, they can simply acquire anybody who starts up and seems to threaten them. Some of our largest corporate acquisitions (and many smaller, less conspicuous ones too) now come from Google, Facebook, Amazon, Apple. When they see a potential rival emerge, they just eat them. A number of venture capitalists and entrepreneurs I spoke to for this book said that (especially in certain strategic areas like data analysis, or smart cars, or AI technologies), we now basically have these dark zones, where nobody else can enter and challenge the big and powerful. Or if you do start a firm, you might not start it to create a standalone company. You might start it more as a talent farm, with the hope that somebody will need to buy you, and just eat your employees.

But here especially I would stress that our US economy still runs on 70-percent consumer spending. So when you have labor trends like this, you ultimately diminish everybody’s income. Workers’ incomes stay flat, because the number of potential employers keeps decreasing. And then the gig economy brings all of its own problems, with so-called contractors receiving no benefits and no protections. Uber hoovers up all the data from a driver’s car, and owns everything, and the driver takes all the risk, and gets subjected to the whims of these algorithms.

Or you mentioned Starbucks, which provides this stark example stretching beyond the typical ways that we think about surveillance capitalism. Starbucks of course does know a ton about you. But it also has these powerful scheduling algorithms that can (in a very precise, real-time way) adjust the number of workers needed in any given store. So if I’m on the slate for Starbucks, they might call me right now in the middle of this conversation. They might ping me on my phone, and say they need me at a certain store in 45 minutes. I might have to drop whatever I’m doing. The New York Times ran that wonderful and really disturbing piece a couple years ago describing this kind of everyday havoc wrecking workers’ lives. Here again this idea that technological innovation lets you skip the liability, skip the regulation, skip abiding by all the laws your competitors abide by, seems just ridiculous. No wonder the union movement has made it a big target to organize these gig-economy workers.

We still haven’t addressed two basic hypocrisies your book presents so strikingly, occurring on a national and international level. First in terms of domestic politics, could we take your account of certain Silicon Valley players reaping the benefits of a preceding generation’s publicly funded research investments (and trustbusting of Microsoft), and calling for significant new public spending in education and infrastructure — even as these firms and their leaders espouse the merits of a lean neoliberal state in other contexts, and offshore their own vast revenues to avoid paying their fair share of taxes? What could Americans outraged by such hypocrisy learn, for example, from the models of Nordic countries and of Israel ensuring that the public gets back a significantly greater cut of post-public-investment profits?

We’ve finally started to see in the US a conversation about these models from other countries. You mentioned Scandinavia and Israel, where the public sector actually takes a stake in certain companies and technologies funded by taxpayer research. So think again about the smartphone. Every single smart thing in a smartphone (the Internet, GPS, touchscreen functions) comes out of DARPA, out of Defense Department research. There is no reason why, in a free-market society, you couldn’t have the government take an equity stake in some firms exploiting these technological breakthroughs. I’m not saying to go back post facto and demand a stake in Apple or Google. But going forward, we could have taxpayers benefit from their own research investments. That just sounds like a natural argument in some of these other countries.

You also hear calls (especially in California) for creating a kind of digital sovereign wealth fund, a digital dividend — acknowledging the fact that our personal data now provides the raw material for this new digital economy. So how might we receive some value back from that data extracted from us? Well, we could develop some way to value all of this data. We could implement a digital tax of some kind, with the revenue put in a fund and given back to individual citizens. We already have the successful models of states like Alaska and Wyoming doing something similar with mineral rights and carbon extraction.

And then for a second, globally scaled hypocrisy, you point to something shameless in today’s domineering, monopoly-pursuing platform firms promoting themselves as national champions needing special protections to fight off Chinese rivals, supposedly on our behalf. Here could you start from the premise of a geopolitical struggle emerging against an omnivorous, unconstrained, data-hording China, and explain why we still shouldn’t consider Silicon Valley’s Big Tech firms (complicit in China’s authoritarian surveillance, stifling technological and economic dynamism back home, actually pushing would-be innovators out of the US) our defenders, deserving our generous support?

So I do see that geopolitical divide already happening. I see us already moving, for various reasons, towards this bipolar or even tripolar world, in which the US, Europe, and China may go different directions on digital trade laws and protections. So let’s assume these trends continue. Well, companies like Google, Facebook, and Microsoft all have operated in China for some time. They now do depending more or less on whether China allows them into the market. They would love more access to that market.

Now, think about the part these companies play in our own national-defense strategies. Think about this new era of statecraft and warfare becoming much more digital, with wars increasingly waged online — with AI, cybersecurity, data becoming the new weaponry of this digital age. In that context, these tech companies arguably have become more important to the national interest than, say, a Raytheon or typical LA-based player in the military-industrial complex. So why don’t these tech companies have to abide by similar rules? I mean, Raytheon absolutely cannot do business in China that same way.

But what I find most egregious, when someone like Mark Zuckerberg or Sheryl Sandberg or Eric Schmidt goes to Washington and says “We can’t win against China unless you let us get even bigger,” is the cynical way that this undermines competition and really our whole model of economic growth. Again, if you look at how innovation always has happened in Silicon Valley, it comes from small firms. Once these firms go public, they basically stop innovating. They come under intense pressure to just keep handing back money (which, by the way, is mostly what the Big Tech companies do now — they give back the majority of cash to shareholders, instead of pouring it into investments in the real economy). So if you truly want to see a large vibrant ecosystem of thriving small businesses, you can’t have a handful of companies dominating that ecosystem. And similarly, I would argue, you can’t expect these dominant firms to out-big China. China does top-down very, very well. The US historically has done bottom-up very, very well. So I would say that we should play to our national strengths, and strive to enrich the larger ecosystem, rather than falling for this incredibly cynical and rather paranoid line that: “If we can’t keep growing bigger as companies, then China will be over here eating this country’s lunch in the next decade.”

How would you personally parse boorish Trump-style China-bashing from a more sober call for reducing or even ending our reliance on Chinese equipment and supply chains — and for rebuilding our own industrial infrastructure?

I consider that a crucial issue. For a long time I’ve been going to China. I love China. I think of China as such an amazing and impressive country. And in fact I’d say that the Chinese have executed Alexander Hamilton-style, American-style industrial policy much more successfully than America itself over the past few decades. I think China’s doing great for China. But it always has stood out to me that the Chinese have a fundamentally different kind of market system — with its protected sectors and its ring-fenced strategic areas, where they always favor their own companies.

I’ll give you a quick example. Maybe 10 or 15 years ago I was in China talking to the CEO of a big Danish wind company — the top company in China’s wind-power market at that time. I asked this CEO about future prospects. And the CEO said: “It’s going quite well. I think we’ll be number four about five years from now.” And I said: “What? How can you call that ‘going well’?” And he said: “Because Beijing told us that’s how it’s going to be.”

China’s economy runs that way. So frankly, one reason why Trump’s trade message resonated with a lot of people came from calling out this hypocrisy which US companies increasingly complained about during the Obama administration. I dislike Trump’s rhetoric for any number of reasons, but I do think we need to recognize that the rules of the road cannot stay the same. And again, to be frank, I don’t see China allowing an even playing field for multinational companies anytime soon. So I do believe that, for a lot of reasons, we should re-shore. We should look more regionally. I mean, just-in-time production, energy costs, the risks of an infiltrated supply chain all suggest that some hyper-globalized, hyper-financialized model maybe isn’t the best way to run your company right now. Maybe you should try to get a bit more local. Maybe that would decrease your energy footprint and financial risk, and would actually enrich the ecosystem back home. To me that sounds like a win-win. That doesn’t sound xenophobic.

Finally then, your historical account of Big Tech’s emergence as too big to fail, in the mold of a preceding decade’s financialization-fueled firms, picks up persuasive force as you compare how both industries rely on a vast information asymmetry relative to consumers, on a lavish lobbying-intensive approach to government oversight, on abstracted conceptual tools guarded from public view (poorly understood even by some of their strongest advocates), and on an insatiable growth model that nonetheless doesn’t produce many jobs. By extension, you point to an insufficient or ineffectual post-2008 regulatory paradigm, and you caution against allowing some of the most problematic Big Tech participants, most needing regulation, likewise to write their own new rules today, and to play an outsized role in answering Don’t Be Evil’s all-important question: “How can we make sure that the digital age is one that enhances well-being, creates sustainable growth, and supports rather than erodes our system of liberal democracy?” So for one regulatory contribution of your own, could you sketch what a new “digital FDA for the brain” might look like?

You made that comparison well. For both the largest financial institutions and the large tech platform firms, we can picture an hourglass, with its tiny middle, where all the money and information flow through. Both Wall Street and Silicon Valley have a lock-hold on that middle. They can charge whatever they want for what flows through it. In Silicon Valley, they might not charge in dollars, but they charge in data (potentially more valuable, depending how you slice it). And they charge you in this completely opaque way. Only they get to see everything going through, and precisely how it does get through. That complexity makes this economic activity very, very difficult to regulate. But here I’d return to the same kinds of questions I asked in 2008: is what you’re doing in the interest of the public at large? And I believe that, by a variety of measures, the social cost, the political cost, the economic cost of firms like Facebook really has started to outweigh the benefits. I think we need to have a very clear and open public discussion about this.

We do today have multiple agencies in Washington and in Brussels investigating the largest tech players. We also of course still see a lot of risk for regulatory capture. Elizabeth Warren recently called out the Facebook policy chief, who worked for George W. Bush. Warren wants to clamp down on this revolving door — which certainly brings in Democrats just as much as Republicans. And I do see momentum for change here. I think we need a new independent body. I’d stress the word “independent,” because when you start to dig into this topic, you find out how many academics and supposed experts actually operate as paid consultants for the industry. You have a very, very hard time today finding independent voices. But we need to find those voices, and put them in a room together for a good 12 to 18 months, and put a pause on the way our digital economy gets shaped, and look at all the different factors.

Let’s look at job creation. Let’s look at productivity. Let’s look at the monetary worth of data, and at how much revenue should go back to citizens. Let’s look at national-security concerns. Let’s look at tax and trade in the digital era. Let’s get a 360-degree view of this industrial revolution of our time. And you know what? Let’s get the rules right this time around. Here that idea of creating some kind of FDA for technology comes to mind. We now know that digital activity is addictive. We can see its effects on our brains. We can see it affecting our children. We can see teens in this country spending about seven hours a day on screen. I suspect that, 20 years from now, somebody will make a documentary very similar to The Insider, which looks at Big Tobacco (but now looking at how the folks developing today’s technologies knew what was going on, and just didn’t say). Or alternately, regulators really need to step up and take charge. Clearly this industry cannot regulate itself.