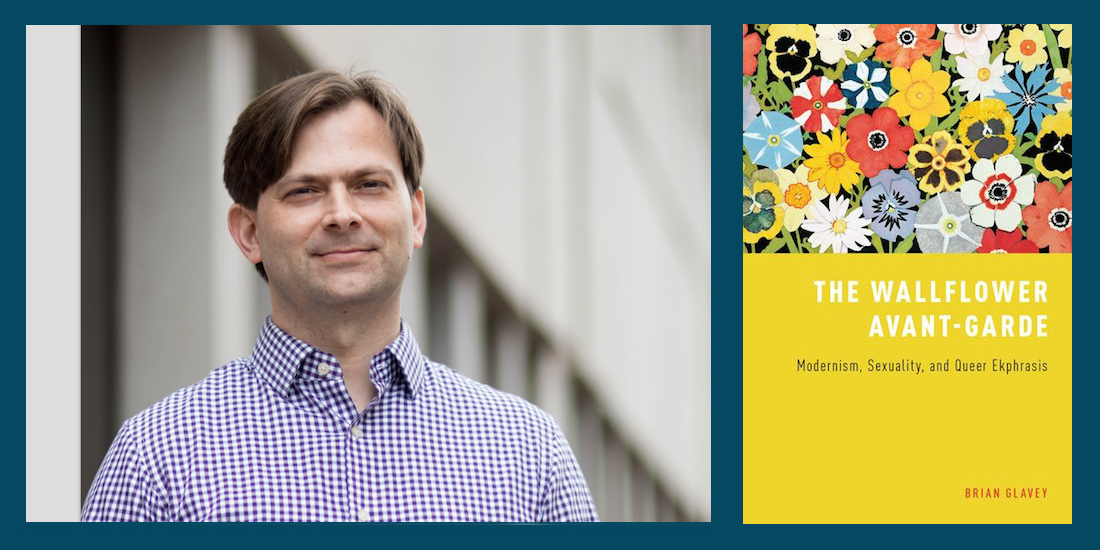

What do we really look for in verbal descriptions of visual art? What can we see about ourselves (as writers, readers, thinkers, talkers, theorists, scholars — but also as potential art objects) amid the overlapping identifications and discoveries and inventions at play? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Brian Glavey. This present conversation (transcribed by Phoebe Kaufman) focuses on Glavey’s The Wallflower Avant-Garde: Modernism, Sexuality, and Queer Ekphrasis. Glavey is an associate professor of English at the University of South Carolina, and the author of essays appearing in American Literature, Criticism, PMLA, and The Year’s Work in Nerds, Wonks, and Neo-Cons. He is currently writing a book on postwar American poetry, queer theory, and the poetics of oversharing.

¤

ANDY FITCH: More than most scholarly books’, your acknowledgements section sounds like a party, perhaps a college-town party, a little on the boozy side, a bit socially/psychologically/epistemologically fraught. Could you describe emergent trends, affinities, enthusiasms, tensions within various overlapping theoretical, intellectual, professional, cultural, interpersonal communities during the period in which your development of The Wallflower Avant-Garde took place? Could you maybe place that trajectory alongside what I at least sense as a tension circulating throughout this book between reading as impassioned attachment, versus reading as observing protocols of the profession — particularly as you progressed towards a completed book manuscript?

BRIAN GLAVEY: I’m delighted that you begin with the acknowledgements. At a certain point in the struggle to complete this book it really felt like I needed to finish it in part just so I could publish my acknowledgements. But I know what you mean about a kind of tension that they might highlight, though I wouldn’t describe it as a tension between professional and nonprofessional modes of engagement. To be honest, I think that an acknowledgements section is maybe the most professional part of a book, really. Which is just to say that, to me, the important protocols of the profession have precisely to do with impassioned attachments, with putting texts in relation with other texts and, just as crucially, with other people. I try to highlight attachments not only to the texts I discuss, but also to the community of friends, mentors, and scholars with whom I was able to think while writing about those texts. For me, those attachments to texts are really unthinkable apart from the attachments to these people. The kind of criticism I practice attempts to make interesting things more interesting (that’s the profession, to me), and one achieves this, in part, by having conversations with people one admires or maybe disagrees with. The heart of this book crystallizes around an idea of formalism as inherently relational, as a form of sociability. Certainly, at times, those relations probably get a bit boozy and woozy. But one way or another, studying texts establishes not only a relationship between reader and poem, or reader and author, but crucially between a reader and a class full of students, a bar full of friends, all the people with whom you figure out what you really think about things.

Still for me the main tension circulating in The Wallflower Avant-Garde has to do with the obvious fact that a book isn’t, as it turns out, a party. Writing a book, reading a book…even while those acts generate an important kind of sociality, it’s important that they do so via a kind of retreat or withdrawal. For the aesthetic, in other words, the anti-social and the social aren’t mutually exclusive alternatives. They’re wrapped up with one another in interesting ways. That’s a big part of what I hope to highlight with the idea of a wallflower aesthetic, but negotiating that does wind up a bit psychologically and epistemologically fraught. Like, at one moment, you can feel elated talking with students or friends about these attachments to works of art. Then at other times this suddenly can feel isolated and almost willfully unimportant. You think: I should be out in the streets, not spending all day cogitating about Gertrude Stein [Laughter].

Well perhaps probing the particular types of focus that this book provides eventually can point us back towards broader social and political communities. So could you first parse working definitions and applications of ekphrasis, both on a historical continuum and in our recent present? Your book points to a long-term literary past, for instance, in which critical reflection on ekphrasis addressed description in general, or a streamlined 20th-century conception of ekphrasis as the verbal representation of visual representation, or New Critical prioritizations upon ekphrasis as the emblematic gesture of literariness itself, the quintessential verbal icon. And as we here move towards present-day confoundments of objective description, subjective emulation, projective identification, queer affiliation, I wonder if you also could begin to outline ways in which the scholarly and theoretical work you find most exciting might come to recognize itself as engaging, embodying, exploring adventurous possibilities in ekphrastic practice — rather than just writing “about” ekphrasis. Your recounting of epic’s convoluted narrative arc, for instance, reminded me of how close readings offer their own artful embellishments, often ornamenting ostensibly austere argument-driven scholarly projects.

That makes sense. Ekphrasis interests me not only as an object of study, but as a methodology. It is a concept with an ambivalent place in the history of literary criticism. In certain versions of New Critical scholarship, for example, ekphrasis becomes nearly synonymous with poetry in general. The literariness of literature, for certain mid-20th-century thinkers, gets identified with ekphrasis, as though poetry is only poetry to the extent that it’s also pottery. On the other hand, it gets figured elsewhere as a kind of verbal excess, associated with purple passages or excrescent moments of narrative delay. So, as with formalism in general, everybody ends up disagreeing on just what they mean by this most important concept. This profound “all-or-nothing” logic surrounds the whole idea. I want to take that sense of conflictedness, that sense of confusion as inherent in the term (and, relatedly, in the idea of form itself), not as some sort of accident that theory just needs to clarify.

Now that I think back, I did want explicitly to take the ekphrastic writing I studied as a model for the way I would write this book. I don’t mean to establish any categorical imperative here, or to diagnose “how we read now” or anything like that. But I feel like we haven’t really acknowledged the extent to which our disciplinary modes of engagement with texts can have more to do with talking and writing (with teaching, in one way or another) than they do with reading per se. I think ekphrasis, as an unrepentantly aesthetic variant of description, highlights this in a productive way. At any rate, that feels useful as a description of my own critical practice, as a way to think in conjunction with other writers and texts, explicitly as a mode of response and of relating to people and to the world through imitation and identification. And over-identification. Every now and then I cringe a little at how different each chapter of my book sounds tonally — the Stein chapter is punnier, the Ashbery chapter daffier. But all of that happens because taking on the vocabulary of a text as I study it seems like a way to amplify and better understand it. Plus there’s a distinctive pleasure in speaking other people’s languages, and I think that’s part of what close reading is about — that way of both attaching to texts and inventing them. Criticism should be more explicit about that ambiguous line between ventriloquism and objectivity.

Your book definitely points toward the value of reparative practice for a reader, a scholar, a teacher. Could you sketch the generative role that specific models of the reparative (perhaps Eve Sedgwick’s critical work especially, but also, say, a reparative formalism as crystallized in Djuna Barnes’s novel Ryder) have played, and to which “readers might turn not for redemption but rather for…capacity for the unfinished, a permission to carry on in a fragile world of great need and little comfort”? Could you describe Sedgwick’s and/or Barnes’s precedent in helping you to conceive of a critic potentially fusing the projects of impassioned amateur reader and modernist poet/collagist? Could you begin to lay out how/why reparative reading models have prompted you personally towards an interest in manipulating materials rather than (or as one among many potential means of) mastering texts? Could you articulate how tapping non-totalizing valences of narrativizing structure, of intertextual resonance, tone, linguistic microtexture, help you not only to conceptualize but to enact ekphrasis’s own attempt to “tell the story” of its picture, to fill the gap, to abate (and/or betray along the way) its own erotic attachments, its own “illusions of wholeness,” ever giving way to realizations of lack, ever ready to get “fooled over and over again”?

So, yes, absolutely Sedgwick’s writing on the reparative remains the most important theoretical resource for my work, and I do find particularly generative this idea about not mastering a text. A grand permissiveness comes from that letting go. But an equally important lesson might have to do with acknowledging that you have a desire towards mastery in the first place. Responses to Sedgwick’s reparative practice often leave out how much this model remains rooted in one’s own sense of culpability and destructiveness, and how the reparative impulse emerges explicitly as a kind of defensive response to that aggression. It’s crucial that the paranoid impulse isn’t something you can or should just walk away from. Sedgwick doesn’t say: “You should try not to have a strong theory about anything.” I mean, it would be crazy not to be paranoid. We should acknowledge that we have this impulse towards mastery, this impulse towards control, and absolutely we should feel uncomfortable and skeptical about that. But it’s also crucial to find forms of response that allow for a realistic conception of agency that doesn’t pretend to be either all powerful or totally powerless.

My abiding point is that there’s always an explicitly aesthetic aspect to this conception of mid-range agency. It’s important, for instance, that Sedgwick’s reparative turn really gets tied up with her turn towards crafting, towards textile art and collage, toward the wabi-sabi. She describes in a really moving way how such work can offer a reprieve from this desire for total control (a kind of crushing fantasy probably recognizable to a lot of people who come to think of themselves as good with words). There’s this desire when writing to get it exactly right, and this impossible fantasy of omnipotence can torment you. In contrast, Sedgwick suggests that when you make a collage or work with another craft, you can maybe take for granted that you’re engaged in a more limited adjustment, a modification of material that already exists in the world with its own kinds of agency. That’s also the ekphrastic imperative. Sure there is often an agonistic element or desire for control, but there’s also this fuller relational range with which writing encounters and resembles images. A writer might be jealous of, desirous of, or just like hanging out with a painting. Criticism imagining itself as a craft in the arts-and-crafts sense, trying to make something with something that already exists, can usefully incorporate and learn from those different modes of relationality.

Sure in terms of criticism as a craft acknowledging its own impulse towards mastery, or when you frame ekphrastic projects as some normative battle between the sexes (with literature reasserting its masculine authority over the fetishized, feminized, ekphrastic object), or as you begin to articulate how various ekphrastic models fail to uphold any such binary (never satisfied by some apparently straightforward act of seeing, always throwing some homosocial proclivity towards sharing into the mix), or as you begin to outline a queer ekphrastic mode in part dedicated to the proliferation of multiple unpredictable means for desire to attach to undervalued works of art, or as you begin to speak up for traditions prioritizing same-sex and sister-art and sissy-art ekphrastic practice, I’ll wonder if you ever conceived of this book’s (or maybe some future project’s) chapters addressing not necessarily Stein or Barnes, but Walter Pater, Roland Barthes, Eve Sedgwick, Wayne Koestenbaum — thereby prioritizing ostensibly critical texts. I’ll wonder if/when critical ekphrastic practice, slipping away from its charge to be masterful, still faces the threat of being derided as masturbatorial, and what would be your most positive case calling for a more full-bodied embrace of criticisms’ own erotic, sometimes autoerotic project?

I like this idea of a critical spectrum running from the masturbatory to the masterful and mastering. Modernist ideas of form toggle between those poles, and that spectrum seems important to a lot of writers I think about. The work on the poetics of oversharing that I’m doing right now looks at the aesthetics of Sedgwick’s writings, and their relationship to certain strains of queer theory that resonate with people like Koestenbaum, Maggie Nelson, Michael Snediker and others. In a way, this current work still traces a kind of ekphrastic impulse. Not to dwell exclusively on Sedgwick, but The Weather in Proust opens, after all, with a long, explicitly ekphrastic description of a fountain. It might not be readily apparent how such engagements relate to sexuality, but they highlight a broader conception of sexuality as a kind of formalism, a matter of intricate patterns, the kinds of patterns people generate in order to make sense of a disconnect between the complexity of their desires and identifications, and the limited resources that their culture offers to help make sense of those desires and identifications.

This plays out in interesting ways across your introduction. At first, for example, I can’t tell precisely what you mean when you refer to “form.” Then you get to privileging form not because it offers transcendence, but because it allows for the revaluation of being treated as an image or copy, specifically of gay men and lesbians getting “treated as failed copies of the ideals of masculinity and femininity.” That formulation intrigues me in part because it points to how familiar theoretical foregroundings of an aesthetic negativity might obscure or marginalize certain queer models or processes or poetics of exploratory attachment. But also I just admire how your prose itself takes this roundabout way of delivering its working definition for “form” — implicitly suggesting that our most acute mode of engagement with your own book might involve our identification with its formal process of figuring out what it wants to say, rather than our absorption of its so-called argument. Some old-school composition instructor might circle such pivots from your intro and write in the margins “Where is your thesis?” But your book seems to posit the potential corniness of any such assertive straightforward thesis. To give one much more brief model of this gesture: your prose at first posits the concept of the “sister arts” mentioned above, only to discard this soon afterwards in preference for the “sissy arts.”

Yeah. The way in which I write and think and argue has a lot to do with the fact that certain kinds of ideas, certain kinds of knowledge, certain idioms remain inseparable from the scene of their enunciation. The truth value that interests me connects in profound ways to specific rhythms of sentences I read. I have an old-fashioned investment in the idea that scholars and teachers of literature want to attend to that, that you can’t just consume some synopsis of the argument or plot. I want to show how spending time with texts can become transformative in specific ways — changing the way you think, changing the way you feel. Those questions of temporality seem crucial, for instance, to how I think about the stuttering rhythm and iterative quality of Gertrude Stein’s prose.

I’m interested in formalism as a way of caring about things. That rhythm of process you’ve identified in my own book’s prose shows how this might work. It seems important to think about form as a way of paying close attention to words on the page (to sentence rhythm, to figurative language), and also at the same time to think about form as an abstraction, to use what you find on the page to think or talk about something else. That type of potentially powerful transfiguration lies at the heart of the ekphrastic project. Using a poem to talk about a painting is a lot like using a novel as a way to think about sexuality, or talking about a sculpture as a way of conceptualizing your own identity or making sense of your own feelings — while also talking about a work of art as a way to think about history or political economy. Critical writing can aspire to amplify or extend these processes of transformation, rather than just identify some summarizable idea and deliver it.

You’ve mentioned spending time with texts, and I wonder if I should have clarified from the start that your chapters often offer portraits of individual authors, positing amicable intimacy over any self-distancing mastery of a particular poetic passage. Could you sketch, likewise, how one of Gertrude Stein’s “eye lessons,” with its redirection of a “will to knowledge towards visions of another order,” might privilege cordial familiarity (with its own, in Stein’s terms, “interesting” incomplete access and proximity) over instrumentalist function, straightforward narrative arc, prescriptive argumentation? How might an engagement with the interesting, with its effective mildness, its creaturely warmth and worthiness of being lingered upon, help redirect criticism towards speaking from the familiar — alongside the defamiliarizing? Or since you also describe Stein’s portraiture as pedagogical, what could/should those of us who engage in teaching, scholarship, conference presentations, peer-reviewed publications, professional evaluations learn from Stein’s eye lessons?

There’s a distinctive epistemology in a lot of Stein’s writing absolutely tied up with ideas of interest and familiarity, particularly familiarity with a work of art. A lot of writers in this book display a tendency to confuse works of art and people. In a sense Stein, tries to encourage us to reconceptualize the ways that we might become familiar with a text, as we might become familiar with a friend or loved one. To know an acquaintance presents a different kind of knowledge than we might associate with most forms of criticism. Part of what’s fascinating about Stein is that she has this theory of familiarity, but also that her texts do embody a pedagogical lesson in how they make it possible to cultivate such attentive familiarity in practice. And again, Stein doesn’t just deny that an epistemological drive for mastery exists. She doesn’t castigate us for this will to truth which inspires us to try and come up with some sort of definitive mastery of knowledge of a people or of texts. That remains part of our cognitive repertoire. Stein takes our desire to figure out some secret and gently redirects this, encouraging us to spend time with things — which brings about its own epistemology and deeper familiarity. For Stein, familiarity doesn’t breed contempt. It breeds more familiarity.

Of course familiarity as a concept gets deprecated by a lot of theory and scholarship. Nearly everyone takes for granted that art should focus on making things strange. Stein certainly produces strangeness, but she also thinks about how we can pay attention to the familiarity of things in a way that doesn’t necessarily have to defamiliarize them. Something about the hominess, the undercurrent of domesticity in Tender Buttons, seems really important for her. She wants to hold onto the familiar boringness through which one can form a pleasant attachment. She makes that visible, then creates art practices that might multiply these forms of becoming familiar with the world. She wants to foreground art’s ability to help us appreciate the things that we recognize, or the things that we do know. Theory of course can contribute to this project. Stein can help us appreciate the knowledge we already have, and acknowledge the fact that you don’t just learn something once and know it forever — that you constantly relearn the same lessons over and over again, that being a thoughtful and intelligent person includes learning/relearning in those ways.

I sense erotic pleasure lurking in this potential learning, or just in what remains potential. And so I turn to Bruce Nugent’s literary persona, to the posture of languorous lassitude, to your subsequent formulation “no happiness without happenstance.” That particular amorous arc across your book left me wondering how many billions and billions of thesis-driven arguments have precluded happiness from the start, or why so many of us remain engaged in an enterprise destined to make so many others unhappy, rather than to turn them on.

Well part of ekphrastic pleasure definitely involves tapping the potential within an image or an object (a picture being worth a lot more than a thousand words, and vice versa). The fact that we can write hundreds of poems about a painting speaks to that painting’s potentiality — or to the potentiality located somewhere between the object and the subject encountering it. This potentiality can be generative, amorous, languorous. Nugent taps this potentiality in part by performing something like eroticized indecisiveness. Nugent’s protagonist considers writing, considers painting, but maybe doesn’t want to do either, or maybe not right now. I think of this in relation to Giorgio Agamben’s notion of impotentiality, an acknowledgement that potential only remains potential so long as there is a real possibility that it will not be actualized. That seems important to Nugent, and also to the critical tendencies you mentioned. It also seems relevant that Nugent publishes this amazing story and then really doesn’t publish anything of comparable significance for the rest of his life. Something about that languorous willingness to linger in the moment of potentiality becomes productive, but maybe only can stay productive if it doesn’t lead anywhere.

And with the added, lingering drama of Nugent presenting the first openly gay African American literary text.

Exactly.

And also with (again in terms of form) Nugent’s ellipsis-centric prose page perhaps tracing/depicting identity itself as a form of dense textuality, race itself as a form of dense textuality, synthesized sexual/racial subjecthood itself as a form of dense textuality.

And again, the way that Nugent responds is almost to shrug off any attempt to define his race, gender, or sexuality. Part of what I find moving is how that text doesn’t even acknowledge the existence of homophobia or racism. In a way, Nugent’s text can’t be bothered. There’s something beautiful about how it lingers in states of potentiality and a kind of ambiguity.

From this posture of lingering potentiality, could we pivot to Frank O’Hara’s posing and/or statuesque presence? You describe O’Hara’s generative practice not only of rushing about town (the familiar Frank O’Hara), but of patiently performing what you call “paralytic” self-mimesis. O’Hara showcases the courage to become not just a heroic Ab-Ex-era artistic subject, but a fetishized artistic object of the scrutinizing gaze (thereby fusing any number of projections, identifications, desires).

There’s an irony at the heart of O’Hara’s reputation, I think. There’s the ubiquitous image of O’Hara as this poet of mobility, buzzing around the city, which is absolutely accurate, of course. But O’Hara is also probably the most visually represented poet of his moment, which means he spent a lot of time standing still while people made statues and paintings of him. That dialectic between motion and stasis seems central to O’Hara’s conception of art. O’Hara’s poetry acknowledges a desire to be attractive in a mundane as well as an erotic sense. Part of what he makes available is a way to think about needing to feel that somebody wants us, that someone finds us desirable or takes an interest in our friendship or even our identity as scholar, critic, or whatever. Professionally, we need to feel like someone notices us. For me, this is a deeply embarrassing impulse. I mean, you try not to look too sad when somebody doesn’t cite your book [Laughter]. But O’Hara finds a way to make those erotic/personal/professional feelings circulate throughout his poetry, and I consider all that part of his ekphrastic project, too — since to write about an artwork means in part to identify with its desirability, its availability, its capacity to circulate in the world in ways a person can’t. For O’Hara, this creates a distinctly queer expansiveness for the self. His identity in poems, in works of art by and about him, enables O’Hara to imagine himself as circulating out in the world. So in a funny way our image of O’Hara as a mobile figure remains dependent on his self-identification with stasis, with himself as a plastic image. O’Hara has to become an object in order to fit into people’s pockets. He’s eager to do that.

On this idea of a desire to attract, I wonder if we should bring in Ashbery. Could you articulate the value in Ashberian shyness, parsing perhaps shyness and shame, with the former positing an intersubjective presence, poetics, politics at the threshold between subjectivity and subjectification — presenting itself as turning away from the world, though, through that very pose, acknowledging its own ongoing (however coy) connection to this world? You offer the image of a child half-hiding, peeking through the fingers with which she has covered her face. You associate this posture with a late-60s Ashberian idiom, one which might address emergent collectivities by opening a poem, for instance, with the phrase “Barely tolerated.” So to follow up on the Ashberian practice of acknowledging, embodying, being turned on by one’s own desire to attract others: how again might criticism itself likewise voice “coy reticence,” perform resonant residence, not just theorize it, but thrust it before us in positive and engaging terms? And keeping in mind that figure of the queer child seeking “momentary reprieve from the lockstep logic of futurity,” how might this child then continue to cultivate such resonant reticence?

That’s really helpful. One intervention I hoped to make with this book involves addressing ways in which queer theory’s investment in affect possibly overemphasizes affects themselves, at the expense of thinking through what people do with these affects. Silvan Tomkins, the affect theorist who stands behind Sedgwick’s work, more or less conflates shame and shyness. I want to distinguish between shame as an affect and shyness as something like an affective style. I want to pay attention to shyness as a transformational method of dealing with or mitigating shame — which really helps to underscore how queer theory can function as a theory of creativity, a theory of how one might create forms of attractiveness or value from the experience of social stigma or embarrassment.

Ashbery’s poetry and criticism model one way of being in the world that negotiates these desires to attract, to get noticed, and to remain private. That tension runs throughout his entire career, with this constant trope of being present while remaining on the side of things. In terms of ekphrasis, this often means lingering around works of art without looking at them directly. Ashbery likes to engage with art as a kind of wallpaper, as something that might blend into the environment. I think this ambient aesthetic maybe helps explain the recent interest that has developed around Ashbery’s house and the curios and bric-a-brac that he surrounded himself with. All of that is a version of what we see in his poetry, the way it connects with a desire to treasure and to feel attached to objects, but also to let them have their own privacy — by approaching them gently and not forcing them to divulge their secrets. Ashbery’s poetry models that shyness, and is not at all naive about the coyness, the attractiveness that attaches to this gesture of withdrawal. It a gesture that says both “Don’t come any closer,” and “Pay close attention.”

When Ashbery’s writing coyly suggests “Don’t come closer,” I’ll also imagining it talking to itself, telling itself not to come any closer, even while incorporating this projected figure into itself — like making yourself alluring to yourself.

Right. That’s another important project [Laughter].

And your epilogue states that “It is never completely clear, when one is reading and writing about art, whether one is inventing what one sees or discovering it.” So in what ways haven’t we yet addressed how your own book, your own broader professional practice, offers “a mimetic model for thinking about relationality in terms other than identity and difference”?

Well it seems crucial to move away from engrained habits of assuming that abstraction and mimesis are diametric opposites, and away in particular from imagining autonomy and imitation as antagonistically opposed to one another. The way that ekphrastic practice constantly creates illusions of wholeness out of failed imitations suggests something useful in regards to letting go of this conception of a text as either open or closed — or, in terms of psychology, as dealing either with identification or with desire. If we could just acknowledge that we constantly engage in multiplicitous ways when trying to manage mimetic practices, then we could have a more capacious sense, a more honest acknowledgement, of what we do whenever we pay close attention to works of art, and certainly when we teach or write about them.

So does that last formulation speak to criticism or scholarship or intertextual engagement as a whole, rather than solely to more narrow conceptions of ekphrastic discourse?

Definitely. One task of literary criticism is to try and expand the repertoire of ways that we can relate ourselves to texts, to works of art, to the people in our lives, to history. The more forms of relationality we can recognize, dignify, and propagate, the more we can integrate these works of art into our lives in more enriching ways, the better. For me, that’s what connects scholarship and teaching. I feel a real affinity between the project of writing a book like this, and the project of teaching a class where you bring together 20 people in a room to present a series of readings of a text which, in the process, creates a specific community that exists in a particular moment in time — adding value to the lives of its members, while expanding the sense of what’s possible.

As we shift back to a more communal register, I recall you pointing early in the conversation to the place for an amorous attunement to the ekphrastic, even amid a more urgent sense of crisis. What has it meant for you to call for this meticulous, often exuberant attention to ekphrastic writing (both as subject matter and as embodied practice) at a historical moment when, say, much contemporary poetics discourse prioritizes work that attunes itself to the ostensibly outside world (and evaluates such work according to the ethical valences of its declared social/activist commitments)? Or how might the history of ekphrasis (and/or specifically queer ekphrasis), with its eloquent engagement on questions of marginality and appropriation, with its etymological roots in ventriloquial practices of speaking up for something and speaking as something, with its acute pains and pleasures of citation, admiration, amatory projection, imitation, emulation, adaptation, make contemporary critical conversations all the more timely and trans-historical — and incisive and supple and subtle and efficacious? Or whom (among contemporary poets, artists, critics, of course any mélange of these categories) do you find offering the most compelling confirmation (or what might such a confirmation look like) of your claim that “Rather than imagining the modernist or avant-garde artwork only as occupying a position of obstreperous opposition, its fist shaking in defiance, we might get a more useful picture of both its politics and its poetics if we imagine its hands tucked shyly in its pockets”? Or given the increasingly intense political polarization since you completed this book, when does it still seem most appropriate, most pleasurable, most epistemically far-reaching to hold one’s hands in one’s pockets?

I did finish this book well before the election, and was just gearing up to promote it in the fall of 2016, only to find that it had come to feel like a relic from another era. If I were writing it now, I’m sure I would feel less invested in this elevation of non-oppositionality. It seems unavoidably clear to me now that we need more opposition. I’ve recently been feeling a kind of excitement that surrounds a growing sense, in the poetry community in particular, of a need for art that explicitly presents itself as activist in ways that the particular subject and style of The Wallflower Avant-Garde doesn’t much reflect. This is not an age for shyness, in a way. That said, we don’t want to be in a position where we fail to develop the aesthetic or intellectual vocabulary to take seriously people’s attachments to what they care about, even when those interests seem less than obviously useful. It seems crucial that we maintain a space where we can recognize the significance and dignity of shyness, say, or the desire to preserve one’s privacy, or the ability to create forms of intimacy predicated on diverting away from direct confrontation with some vision of the social center. All of those attachments, those ways of caring about the world, remain indispensable for our survival. It seems imperative not to lose sight of those ways of being, of ways in which art provides reparative resources, of ways in which literature, poetry, and even criticism give people tools to attach to the world around them — and to carry on and continue and persist in engagements that run parallel to processes of direct protest or other forms of activism. To me this still feels directly political.

So let’s say Sedgwick’s emphasis upon the reparative risks cycling out of favor at this moment: but couldn’t we find in Sedgwick’s self-reflective practice an extremely relevant and generative articulation, a movingly ambivalent embodiment of readerly, writerly, pedagogical complicity — as timely/untimely now as ever?

That absolutely makes sense to me. In the election’s immediate aftermath, I felt a surge of shame about my enthusiasm for the reparative, which came to feel a bit naive. Certain aspects of my book’s approach suddenly felt like symptoms of some kind of complacency about the world becoming a less homophobic place. Initially I felt the impulse to retract 99% percent of what I had written. But of course the artists this book thinks about, and Sedgwick herself theorizing the reparative impulse, are all absolutely responding to a world of injustice, violence, phobia. Reparative reading itself, as you suggest, emerges absolutely tied up with anxieties about suffering (amid the AIDS crisis in particular) and about how one’s existence in the world gets implicated in this propagation of suffering. Something deeply political dwells within this idea of the reparative — beyond even the recuperative value of enabling people to find resources to carry on. Something political arrives through the reparative’s acknowledgement of our ongoing role in systems of oppression, through these explorations of how to deal productively with this karmic deficit that’s part of being a person in general (as well as occupying specific subject positions, specific privileges and injustices). Ultimately, reparation and repair only make sense when the world is broken.