He who hopes for spring with upturned eye never sees so small a thing as Draba. He who despairs of spring with downcast eye steps on it, unknowing. He who searches for spring with his knees in the mud finds it, in abundance.

—Aldo Leopold, Sand County Almanac

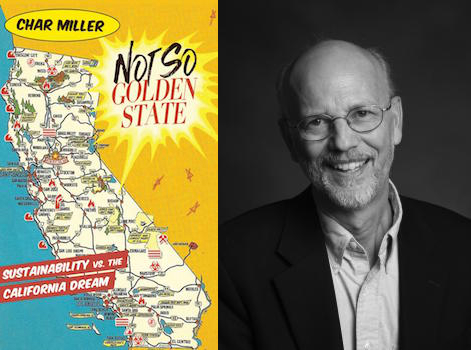

On October 6th, at Hennessey + Ingalls bookstore in Downtown Los Angeles, a group of curious Angelenos arranged plastic folding chairs into a circle and sat beneath an array of art and architecture books. We had come to hear Char Miller, an environmental historian and professor at Pomona College, discuss his new book, Not So Golden State: Sustainability vs. The California Dream. Wiry and bespectacled, with white hair crowning his tanned face, Miller spoke synoptically and read excerpts before ceding the floor to his audience for questions. Not So Golden State, Miller explained, surveys the history of environmental issues plaguing California and the West, with specific attention given to the Los Angeles area. Told through a series of essays — what Miller prefers to call “stories” — the book delves into the tensions that arise when humans choose to “make these disparate landscapes our home.”

Miller divides his book into four sections that neatly address these tensions: “Home Turf” concentrates on Los Angeles, and examines a range of topics, such as the history of the L.A. River, local petrochemical usage, and land management policies; “Golden Shore” tells the stories of our region’s coastline; “Fiery Terrain” explains the reasons behind (and dangers of) our combustible forests, and considers how fire can be beneficial to the ecosystem; “Our Land” steps outward from Los Angeles to such destinations as Zion, Yosemite, the Grand Canyon, and others.

I spoke with Miller prior to his appearance at Hennessy + Ingalls, and we talked about the importance of studying the past through the land, and how storytelling can help us conceive of “the land as community,” to use the words of Aldo Leopold, as Miller fondly does.

“Storytelling is a public action,” Miller was quick to remind me, and his devotion to telling stories is evident from the opening lines of his book: “We tell stories about the land […] We read our way into it.” Miller tells stories to remind us that we inhabit a particular geography, and to inspire collective action. The goal, he said, “is to make us more alert to the fact that we live in L.A., in a place that is imbedded in natural systems.” His book succeeds on this score. In a land of concrete and urban sprawl, where even “the L.A. River doesn’t seem like a river,” Miller takes the reader from coast to mountain to valley, explaining the history of these ecosystems, and revealing how nature remains alive, albeit damaged.

“Part of what, for me, makes a story a story is figuring out the past of a place as much as its present,” Miller told me. “I think the past is present everywhere.” As part of his research, Miller visited the many sites of interest in this book, and his essays blend historical record with personal narrative. In one chapter, for example, Miller uses the setting of a whale-watching excursion off the Orange County coast to dive into the history of cetaceans in the Pacific. The chapter explains the mating and migration rituals of the gray whale, and details how the Chumash and Tongva people once used whale bones to build their houses. Miller then transitions to the uses and abuses of whales during the early nineteenth century, when mariners pillaged the oceans for their oil. He concludes by bringing us back to the present, where he stands with his wife aboard the Manute’a, observing a pod of gray whales “as they [blow] and [sound], their white-blotched flukes on full display; as their dolphin escorts [glide] alongside us, knifing through the sun-flecked water with little visible effort; as gulls and pelicans and terns [wheel] and [drift] across cloudless skies.”

Miller forgoes the detached language of academe, and writes himself into the landscape. The book, told in light yet thoughtful prose, makes personal the region’s environmental past. Miller takes great care to describe the aesthetics of his subjects, allowing us to glimpse and share his spiritual appreciation for the environment.

Miller told me he wants humans to practice humility in our relationship with nature, and he works to disabuse us of the notion that land is just a commodity. He quotes Leopold again on this point: “When we see land as a community to which we belong, we may begin to use it with love and respect.” By synthesizing history and personal storytelling, Miller does just this. In another chapter, for instance, he details how the city of Los Angeles tamed the L.A. River, which once spread its waters across the L.A. Basin and emptied into the ocean anywhere between the San Pedro and Santa Monica Bays. Today, as Angelenos know, the river flows like an afterthought past Downtown, trickling beneath freeways and beside rail tracks, in a concrete-encased channel — that is, when it’s not completely dry. Miller reminds us of the 1938 floods, when the unrestrained river doused neighborhoods across the area and killed upward of 100 people. We have largely drained the power from this watershed, but Miller urges us to notice the signs of life that still surround its currents: “black-necked stilts feeding in the waters just south of the natural bottom narrows; same with a pair of mallards wriggling through a tangle of root and trunk.” He shows us how “nature [survives] in the cracks, like the six-inch waterfall the river had been making as it slowly undercuts the seam between two concrete slabs.”

“We are just members of that community, not its dominant forces,” Miller said during our conversation. He believes that nature “is far more complicated than the human mind can address,” which is to say, it would be foolish to think that nature is under our control; instead, we should recognize and respect our membership in something larger than ourselves. As is the case with the L.A. River, even after humans transform the environment to their liking, nature pushes back and reasserts its presence — a fact further underscored by every earthquake, flood, or wildfire.

This is a persistent theme of many stories told in Not So Golden State: humans cannot fully master nature; indeed, we belong to nature, and our belonging should make us care about our environment. Of course, we haven’t cared a whole lot, and much of Miller’s book is devoted to making that case. He wastes few words describing how the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers razed forty acres of civilian-restored vegetation along Haskell Creek, or how uranium plants dumped “ton after ton of the radioactive sandy by-product into an unlined impoundment area located 750 feet from the [Colorado] river,” or how the Timbisha people were displaced by the creation of Death Valley National Monument in 1933, or how whole neighborhoods in Los Angeles have been sickened by mismanaged oil wells.

But Miller is careful not to dwell solely on disaster stories, what one of his colleagues calls the “green blues.” This makes the title, Not So Golden State, somewhat misleading. Miller’s book is more than a counter narrative to “golden” California. “We have to confront what we’ve done and the damage that has occurred, and be savvy to those consequences,” Miller said, “but if you leave it there you’ve only told part of the story […] I’m really interested in the rejuvenation and regeneration that comes from that. Because that means human beings have agency.” Given the green-blues potential in the field of environmental history, Miller admirably succeeds at balancing his book with examples of what humans have done right.

Consider the tale of the northern elephant seal, presumed extinct in the late nineteenth century due to overhunting. Then in 1892, a Smithsonian Institution expedition discovered eight adult seals on Guadalupe Island, and by 1922, over 200 seals were flourishing. Nearly a century later, that number has risen to almost 50,000, thanks to a series of international laws and treaties that have protected the seals and their habitats. In January, Miller traveled to the shores of California’s Central Coast, where he observed “the prolific colony [of elephant seals] that now sprawled for miles, including a stretch bordering the Pacific Coast Highway.”

Far inland from the P.C.H., tucked between the wooden shelves of Hennessey + Ingalls, our discussion turned at last to our own stories about the land. One participant described her experiences with gators in urban Miami, another wowed us with descriptions of a mountain lion that invaded his L.A. backyard, and a third recounted the time his friends found themselves camped atop a sand dune in a lightning storm. We spoke of the precarious position of Reykjavík, Iceland’s capital city, which rests in the shadow of an active volcano, and we pondered the consequences of our hubris when “The Big One” strikes the Northwest. As twilight receded and chairs emptied, I found myself thinking of a quote by Los Angeles writer and scholar Jenny Price, which Miller mentions in his book: “What we need in L.A., as elsewhere, is a foundational literature that imagines nature not as the opposite of the city but as the basic stuff of modern everyday life.” Not So Golden State, by excavating our past on this slice of earth, is the latest contribution to that literature.