“You think my paintings are calm, like windows in some cathedral? You should look again. I’m the most violent of all the American painters. Behind those colors there hides the final cataclysm.” — Mark Rothko

As a critical theorist who works on aesthetics and who believes that the political is an art form, I am continually haunted by the relationship between violence and images. Is there anything left to say about this relationship, when the triumph of the spectacle seemingly denies any sustained reflection? While the figurative remained a dominant standard for representation until the post-war period, the nihilism of the times brought the very figure of the human as an aesthetic form into question. Humanity had to confront the violence of its own humanism. As Barnett Newman noted, “After the monstrosity of the war, what do we do? What is there to paint? We have to start all over again.” The emergence of abstract expressionism became synonymous with those artists who were so disillusioned by the violence of the human condition, consecrated and mobilized by aesthetic ideas of its perfectibility, they turned away from the figurative to ask still unanswered questions about what it means to be human. While disavowing any formal association with any movement, no artists better captured the early power of this aesthetic turn than Mark Rothko, whose immersive mindscapes are less about the Dante inspired journey into the flesh of the earth, than opening up wounds in time.

Rothko’s life (as is well documented) was full of personal tragedy, culminating in his suicide in 1970. It is perhaps no coincidence he was notably inspired by the great tragic dramatists, from Aeschylus after whom a number of his paintings are named, onto Shakespeare and Nietzsche. In an essay titled “Whenever one begins to speculate,” Rothko draws attention to the importance of Nietzsche and his The Birth of Tragedy. As he explained, “It left an indelible impression on my mind and has forever coloured the syntax of my own reflections in questions of the art. And if it be asked why an essay which deals with Greek tragedy should play such a large part in a painter’s life, I can only say that the basic concerns for life are no different from the artist, for the poet, or the musician.” Such concerns for Rothko were the complete opposite of being “academic” and studiously painting whatever with technical mastery: “It is a widely accepted notion among painters that it does not matter what one paints as long as it is well painted. This is the essence of academism. There is no such thing as good painting about nothing. We assert that only that subject matter is valid which is tragic and timeless.”

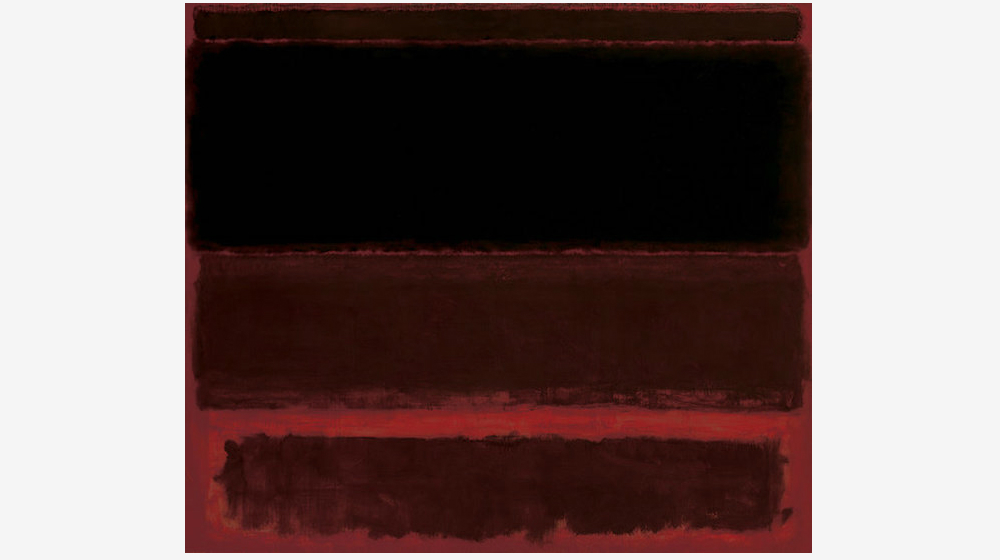

During a recent visit to the TATE modern, I spent most of the occasion in the Rothko room in the privileged company of an abstract artist. Featuring a series of nine large murals, the viewer is reminded by the curatorial instruction of the artists intention who attempted to do what Michelangelo managed at the Laurentian Library in Florence, which for the Rothko “achieved just the kind of feeling I’m after — he makes the viewers feel that they are trapped in a room where all the doors and windows are bricked up, so that all they can do is butt their heads forever against the wall.” One of the lesser populated rooms at the time (Rothko in fact shows the real limits and failures of the modern gallery, horded with tourists passing each exhibit, looking without seeing, having to get through to witness everything with no time to reflect), the dimly lit space, which hosts these large and yet very intimate portraits, creates an immersive experience full of tragedy, terror, violence and yet optimism. Confronted by these large blocks of red, black and maroon colours, in the tranquillity of this setting, slowly you are unsure whether you are entering into the scene or whether the canvas is surrounding you as the active witness or unassuming accomplice to their drama. Being open to this immersive experience, the obscurities of his multiple layers begin to appear and envelope, though not as paint applied onto canvas, but rather as if the colours themselves are emerging from behind the frame. Rothko manages to give depth and perspective, while turning these flat and fixed installations into something truly dynamic in all their tensions. Rothko in fact not only takes us on a journey into the intimate depths of the psychic life of power, he allows you to glimpse at the void as you enter into a different relationship that is lost between space and time.

The brilliance of Rothko is to show how the abstract is not “outer-worldly.” On the contrary it is to take a journey into the intimate depths of human existence. Art was, as he indicated, “an adventure into an unknown world, which can be explored only by those willing to take the risk.” This has always been the fundamental mistake those who critique the abstract in thought also continue to make in their assumptions. Of course, to ask questions regarding the emotional and sensorial qualities of humanity does require alternative conceptual insight and the formation of new grammatical interventions. The scientist armed with their surgical tools is fully capable of dissecting a body, telling you how it functions, but never truly how it feels. And we can often remember how the feeling strikes us, much more than technical procedure, which is really irrelevant to our lived and shared experience. Thus as Rothko shows, to say the abstract is esoteric is born of the greatest ignorance, set in place by all too reductive regimes of truth. Rothko paints a battlefield of the soul, where the intimate is expelled for all to see, where the beauty and pain are revealed as part of all that we are emotionally, politically and philosophically, and where the greater task we confront is to face the obscure beasts that dwell within all our bodies. As the artist himself explained: “it was not that the figure had been removed… but the symbols for the figure. These new shapes say… what the figures said.”

Rothko asks how the eyes perceive, in the radiating darkness of color, the unknown depths of the void. While from a distance, the portraits simply look like linear boxes neatly mapped out, upon closer inspection they appear more like indeterminable gates whose lines are far from limiting or fixed into place. You can imagine their points of entry disappearing at any given moment. The lines Rothko paints flow through the time of the composition. He knows the shadows of emptiness, the temporality of the exhausting gradient to possible nothingness. That the black may swallow up the red any moment, this is the impression; and yet nothing is determined, for in changing depths of the emotional field, filled with unknowable possibility, everything returns. Rothko paints the passion of wound. His canvases bear witness to the scar that is never healed, like the future life of a ghost witnessing its own demise, but yet to be destroyed. He knows the layers, the depths of pain, and the blood that seeps out despite the attempt to mask the violence. Rothko paints the history of humanity, its passion and pain, the slow unfolding of time, life broken apart through the continuous movements of its devastating contradictions. He demands intensive reflection, to have the time to feel every emotion, to short circuit the immediacy of sensation, to be able to feel anew beyond the frustrations of representational schematics and the demands for immediate communication and truth. These portraits are far from static; they are a whirlwind in time, which in the slowness of witnessing the slow re and de composition of color intensifies everything. Rothko is burning. And his flames light a passage into the void for all to enter.

The layering of Rothko’s compositions is truly astounding, and terrifying as a result. What he effectively achieves is to bring light to the disappeared pigmentations of existence. Of course, Rothko’s work is haunted by a silence. There is no other way to engage with their presence. And what lies beneath does threaten to vanish at any given moment as time passes over their almost invisible semblances. Though it’s sometimes difficult to tell if something is emerging or fading away. It’s all a matter of perception. And it is a question of bringing things into light. Still what remains is precisely everything. The layers of history appear in the faintest of defiant specks. There is no nihilistic triumph or victory march into the realm of pure denial. Unlike Goya, Rothko doesn’t surrender or willingly give over to the violence the power of his colours. What is abstract defeats the abstention! And yet still there is no lasting comfort, for the terror of Rothko behind the open terrors of the wound is to confront the simplicity of disappearance as it appears in all its visible manifestations. Yet while nothing is certain, such simplicity on the part of the artist should not be confused for the mediocre. It takes a sophisticated mastery to achieve a visual idea that looking at what remains possible can confronts the notion that things can simply vanish. That history overlays and seeps out, reveals as much as it denies. Such can only be achieved with attention to the historic process.

Rothko shows how the artist is not merely someone who documents history. His work is a form of transgressive witnessing, in which the viewer is accompanied into the void of humanity by the obscure presence of many other poets from history. Nietzsche seemed to fear the abyss insomuch as it was a journey one undertook in solitude and from which one could return truly scarred by the most monstrous disfigurements. Unlike Dante, it is true that Rothko’s gates require you to enter alone. Virgil is not there to hold your hand. The passage into the non-place demands the intensity of solitary reflection. But in the absence of the figurative, the solitude quickly evaporates as this opening or wound in time allows you to both connect with the intimacy of a shared existence and feel the force of those colours, which paint the imagination. But again, unlike Dante, the return doesn’t guarantee paradise. As I left the room I returned back into the adjacent space, which housed Claude Monet’s “Water lilies.” I couldn’t help but feel this was the most violent image I had ever seen — or that every image has the potential to be truly violent if we give to it a certain narrative and eviscerate the human.

So what can we take from Rothko in terms of rethinking the ongoing struggle against the forces of nihilism? The artist asks, as I chose to hear, two very clear questions: What does it mean to disappear a body, a memory or an idea? And why is art so important in affirming our humanity is response to the real force that threatens our existence – the nihilism of the void? Disappearance as Rothko shows is precisely the evisceration of the creative act. It is the denial of a life and a surrendering to violence such that what really disappears is the idea and vision that the world can be different. While it is tempting to see humanity here as a universal subject, total in its unity, which emerges from the realization it is some endangered form, Rothko reminds us that the opposite is true. Humanity lives and breathes through its creative expressions. It outlives the suffocations and forced disappearances, which can either occur through forced complicity or outright annihilation.

Rothko thus provides us with the aesthetic opening through which the world’s beauty and pain can be rethought. His work is the lightning storm that may just be capable of destroying those alters of sacrifice, if only we are truly able to resurrect what remains yet to be discovered about the abstract in thought. Rothko’s call as we might chose to listen is for a timeless poetic reverie — an all too human connection to the ineffable, which recognizing the violence and confronting the intolerable at least asks whether a different order for thinking the meaning of existence is possible. This demands a rethinking of the political imagination and its images of thought. Art as Rothko shows, has an eternal future in the affirmation of its expression. When you give yourself the task of painting with whatever grammatical tools the pain of humanity, he reminds us that you are tracing invisible wounds. Not that the canvas is you as a pure reflection of the world or that you are the canvas like some authentic representational piece in the human jigsaw. There is no canvas as such, only a marking on a surface revealing the wounds of time.

Rothko shows us what was invisible now appears in the lines and movements, the depth of colour not merely representative, but a deep field of sensation which opens onto the abyss of despair. This forces us to give over to an uncomfortable concession. We need to recognize that the violence is also immersive, for it allows no separation between its past and future. But this is not to be defeated. Neither is it to confront violence with a purer “non-violent violence” of whatever critical persuasion. Such orientations are after-all merely a resurrection of the sacrificial by another more considered name. It demands instead a willingness to confront the intolerable depths of human suffering to steer history in a different direction. This cannot be achieved in denial or through absolution. The pain of humanity needs to be felt. This is why the transgressive witness must take that leap into the void. There is no alternative. But what does it mean to truly feel the beauty and pain of all the worlds obscure beasts? How do we even begin to try and find tenderness in its savagery, while being alert to the brutalities of devastating angelic disfigurements? What is the angelic and the bestial — of heaven and hell — are after all of this life, this world. Obscured yet all too real, their ghostly presence fills the void, shape shifting yet appearing with uncertain clarity, from a time within time. But still the unsettling questions continue to appear: Does anybody really have the courage to go there? Who dares to venture into this non-place? And how might we return anew, without being defeated by the pessimism of what is witnessed and confronting there and after? We know that very few send back postcards from the void. It is more than uncertain. It is the unknown unknowns.

The politics of pessimism and the dialecticians of history are merely complicit here in the unfolding drama of a history that remains wedded to the sacrificial model. When Nietzsche says that we need art to prevent us from dying from the truth, he can be seen to be placing art in direct conflict with hope. It’s not that hope is too idealistic. Rather hope is all too pessimistic. It only finds reasons in the yet to come, forgetting the poetics of past and present. Art as Rothko testifies is the counter to such hope. It offers us a resistance in the present, drawing its energies from the past, while instigating an affirmative movement from the abstract to the real, which in the very act of creation positions itself against the pessimism of the defeated. Art thus reveals the tragedy of hope. Hope as a false promise, guided by visions of water lilies and gardens of Eden. It is the actualization of the affirmative conditions of reality that short-circuits the reductiveness of idealism, the living towards a possible future that never was except for now in its actualization. But we shouldn’t idealize ourselves here. Art can undoubtedly speak to the pessimism of humanity. It can also appear enslaved and defeated, as the motor of a history that merely objectifies and consumes the realms of all appearance. And yet even the most pessimistic of artists (worthy of the naming) evokes the pessimistic in the denial of any image of a future, which is foreclosed for all eternity. Its message continues to outlive the investiture of human denials. Art then is not the fire. It’s the air that gives rise to the dancing flame defiantly raging in the wind — the unknowable force that dissolves pessimism as it is mobilized towards the effacement of the image, towards the image yet to come in all its poetic and brutally honest abstract realism. Or to put it another way, what would it mean to do justice to thoughts, words and actions in the same way that Rothko does justice to the intimate aesthetic field of human sensations?