As we remember the late Adam West, who passed on June 9, many will consider the meaning of his signature role in the 1960s television series Batman, as well as in the broad context of American popular culture. Adam West was not merely a camp actor. His performance as Batman articulated a particular set of American values that shaped a generation of young viewers. Adam West himself, in a 1966 interview, understood his role as an American “folk hero,” a “legend,” which represented distinct cultural values in 1960s America. The series, which ran from 1966 to 1968, outlined a strong moral compass and emphasized social values such as individualism and self-reliance. Batman ran parallel to the law and order rhetoric of contemporary politicians, including Barry Goldwater and Richard Nixon, who comprised the emergent strain of conservatism in American political thought. As we remember the life of Adam West, we might consider the historical context in which Batman, his signature role, was produced.

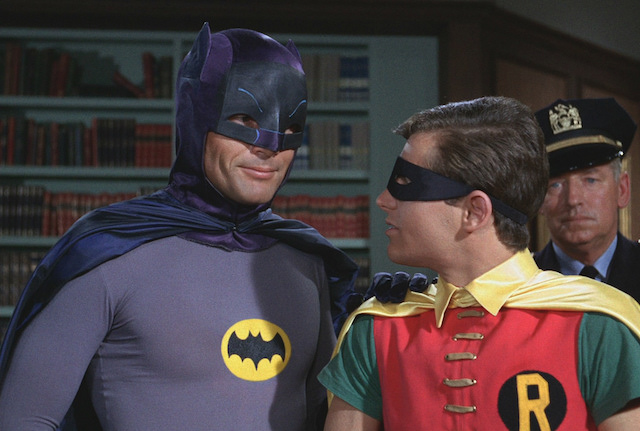

Television producer William Dozier and writer Lorenzo Semple Jr. are credited for creating the 1960s Batman series. From the beginning, it was meant to be “satirical camp,” according to Semple. “Bill Dozier and I had seen millionaire Bruce Wayne and his Bat regalia as classy comedy, hopefully appealing to kids as an absurdly jolly action piece and to grown-ups for its deadpan satire.” Dozier and Semple considered West perfect for the title role. They idealized his “eternal squareness, rigidity, and purposefulness,” Dozier told Judy Stone for the New York Times in 1966. “We can’t have any comedians on this show […] If any actor plays it for laughs, he goes. He’s got to act as if he’s deciding whether to drop a bomb on Hanoi.” Batman was indeed a product of its place in time. But the series may have been more complex than it seemed. It operated on multiple registers, utilizing clever innuendos like some of the best children’s comedy today. “It’s fun and games for kids,” Semple said in 2008. “It’s got a lot of dumb but funny action in it. And for grown-ups, it’s actually very sophisticated, and funny show.” Playing Batman was an “actor’s challenge,” according to West in 1966. “You have to reach a multi-level audience. The kids take it straight, but for adults, we have to project it further.” Adam West was ideally suited for the role.

“Bruce Wayne stands for everything good,” William Dozier explained in a 1966 TV promotion. “Everything that a millionaire could ever do, that’s right, Bruce Wayne does. He doesn’t spend a quarter that isn’t for somebody’s good. And Batman, heaven knows, all he does is risk his life to fight evil. You can’t beat that.” Adam West brought this dynamic, teaching morals and righteousness to Batman’s younger audience, to life. Batman emphasized individualism and self-reliance, but also charity and social justice. Adam West’s character battled evil, but he framed his struggle in teachable moral lessons that could shape a child’s worldview. “If anything, Batman and Robin represented the wish — the dream to do good, to be a morally good person,” said Burt Ward, West’s costar, to the New York Times in 1966. “I don’t think it’s wrong to go out and catch crooks.” Adam West’s Batman professed a sense of moral virtue, and the series in its entirety taught the importance of civic responsibility. Gotham’s inept government perpetually rendered the city susceptible to destruction at the hands of various villains, which perhaps reflects contemporary urban crisis anxieties. Throughout the 120 episodes that aired during three seasons, the people of Gotham begged Batman and Bruce Wayne to run for mayor twice. In one episode, Batman runs for mayor against the Penguin and wins, but ultimately defers the position to the incumbent Mayor Lindseed (a thinly veiled reference to New York Mayor John Lindsay). In another two-part episode, “The Joker Goes to School” and “He Meets His Match, the Grisly Ghoul,” Bruce Wayne is pressed to run for mayor. Philanthropist Mr. Vandergilt visits Wayne manor and lists the city’s woes, in another possible reference to the 1960s urban crisis: “But Gotham City needs you. Think of our problems: the snarl of traffic, a water shortage, and now these recurrent power failures.” Bruce Wayne, like Batman, however, defers, declaring that “the good works of my Wayne Foundation require that I stay above the brawl of politics.” Batman depicted a precarious government, often needing rescue. The city relied on Batman, an extra-legal entity, to provide law and order and a sense of security for its citizens. Batman was a cultural reflection of the growing conservative political rhetoric in America during the late-1960s and 1970s, in which right-wing politicians, including Richard Nixon, and ultimately Ronald Reagan, characterized the state as weak and inefficient, championing free enterprise and competition as a scale of social good.

Above all, Adam West brought a human richness to the series. While his portrayal of the Caped Crusader was often clunky and rigid, West’s performance emphasized human vulnerability, which might account for the lasting impact of the series. “You can’t play Batman in a very serious, square-jawed, straight-ahead way without giving the audience a sense of maybe there is something behind that mask trying to get out,” West reflected in 2006. Fans told West that his performance held up very well. “They love it and they watch it over and over, and their kids watch it with them,” according to West. “I guess there was something really human and vulnerable in there, because if people have some kind of affection for the lead character, that’s when a series will have some kind of longevity.” In addition to civil and moral virtue, Batman taught and continues to teach children empathy, even for the villain. “If I had the chance to do it all over again I would,” West said in 2014. “I am the luckiest guy in the world because I got to create a character that lasts and that people love.”

Much more than a camp series, Batman was a moral compass for generation of viewers. While the series, like any other, might have reflected the politics of its time, it also opened a space of imagination and possibility. “I’ll probably be remembered as ‘Batman,’ mostly,” West said in 2006. “It’s okay with me because it’s given so many people worldwide so much pleasure. Many actors don’t get the opportunity to do that.” But Batman provided viewers with something more than pleasure. We should not forget that Adam West’s Batman was a kind of “folk hero” that conveyed cultural meanings particular to 1960s American youth.