Meet Twin A and Twin B of Jane Austen books. One twin stayed home and became famous while the other traveled around the world and was forgotten. To understand the differences and similarities of twin reprintings is to see how the prides and prejudices of book collecting have cordoned the reception history of even a writer as acclaimed and well-watched as Jane Austen.

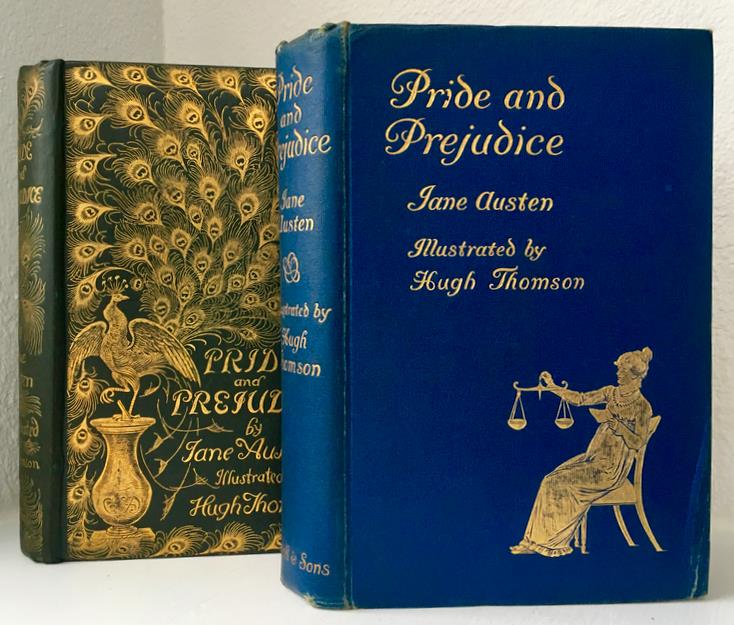

Born five years apart during the 1890s in London, these two books — dressed outwardly in different publisher’s bindings — are in fact identical offerings of the same illustrated Victorian edition of Pride and Prejudice. Most fans of Jane Austen will recognize the gilded green volume on the left, born in 1894 to publisher George Allen and illustrator Hugh Thomson. Known as “The Peacock Edition,” this is, hands down, the most fetishized and most collected reprint of any Austen novel, as evidenced by the t-shirts, tote bags, comforters, pillows, mugs, and scarves that currently traffic in its cover image. On the right, in blue cloth and with a smaller gilded illustration by Thomson, is its unsung bibliographical twin — published in 1899 by George Bell and Sons, a London firm specializing in educational books. Issued by two different publishers, both books were printed from the same plates by Charles Whittingham and Co. at the Chiswick Press and include the same famous preface by George Saintsbury (the one who coins the term “Janite” for an Austen fan) and the same 160 line drawings by Hugh Thomson. The central texts of these volumes match page number for page number.

From the beginning, however, the twin books were valued differently: Allen’s green volume sold domestically for the solid upper-middle-class price point of six shillings while Bell’s identically-sized blue version sold more cheaply in the foreign market for three-and-a-half shillings, a difference of 42%. The original price of a book can determine its fate. Bell’s cheaper blue version is virtually unknown now and far rarer than its famous and dearer green twin. Remarkably, WorldCat or OCLC, the ultimate online inventory of the world’s libraries, records only one known copy of Bell’s Pride and Prejudice on the shelves of institutional libraries, whereas it logs over one hundred copies of Allen’s identical edition.

Some books may be more equal than others, but much can be learned about Austen’s early audiences from her unsung and castoff reprintings. In 1899, Bell issued this blue Pride and Prejudice for its Indian and Colonial Library series, “for circulation in India and the Colonies only.” India, after all, was not considered a mere colony but an “empire.” This rare survivor of an inexpensive publisher’s series is representative of that neglected category of 19th-century books doing the heavy lifting of building Austen’s early reputation — of dispersing her celebrity across the globe and across class boundaries.

With the help of private book collectors, I have for some years now been hunting for early and cheap reprintings of Jane Austen’s novels that, starting in the 1840s, made her popular with working-class audiences long before she became the sanctioned darling of the Edwardian elite. Only a few of these low-priced versions were so-called colonials, like Bell’s Pride and Prejudice. Many others were cheap domestic reprints, because Austen by the 1890s was sold in printed paper boards for 1 or 2 shillings, and in flimsy paperbacks for sixpence and even thruppence, at Victorian book stalls and railway stations. These cheap and hardworking Austens, however, have largely been ignored by historians whose eyes remain stubbornly trained upon the highbrow and middle-class books found in academic libraries: rare firsts, handsomely illustrated tomes, or “authoritative” editions. The myopia of the scholarly gaze is an unintended consequence of standard collecting practices. Read to bits, sacrificed in paper drives, or simply discarded, the cheapest versions of Austen’s novels live the hardest lives. Few of these shabby and tattered reprintings found their way into the sanctum sanctorum of rare books libraries or special collections, even though cheap books help make authors canonical.

Between 1894 and 1911, Bell’s Indian and Colonial Library series sold over 1,433,341 books, including this Pride and Prejudice. With at least 1386 titles in the series, that amounts to an average run of just over 1000 copies, sold “in cloth, gilt” for three-and-a-half shillings or “in paper wrappers” for two-and-a-half shillings. While the widely-admired Peacock edition of Pride and Prejudice, launched by Allen in November of 1894 amidst the hurly burly of the domestic pre-Christmas market, is duly recorded in bibliographies and extensively discussed in academic articles, Bell’s cheaper-but-faithful reissue for export does not even make it into the standard inventory of Austen editions by her most fastidious bibliographer David Gilson. The physical similarity of the two books suggests the publishing houses came to an arrangement, so Bell’s book is not a piracy. Bell specialized in educational texts for school rooms that stimulated primary demand by educating the wider public about the value of – in this instance – Jane Austen. The success of exported series such as Bell’s Indian and Colonial Library were extending the reach of London publishers. Scholars continue to debate the impact of colonial distribution of English fiction on the literary canon, for the reading lists favored at home still seem to have differed from the British canon shaped abroad. But while Allen was preaching to the middle-class choir with his pretty six-shilling gift edition of Austen, Bell was bringing the author to new audiences with a more cheaply-produced-but-identical-edition. Bell’s version is indeed derivative, but only his version set out to garner audiences for Jane Austen in Dunedin and Bombay. What became of those 1000 copies?

Cheap reprints should no longer be treated as the dregs of book history, shunned by scholars and bibliographers as inauthentic for their intolerable cheapness as much as their supposed “errors.” (Bell’s central text is, of course, identical to Allen’s, although the paper used is of lesser quality.) Only by tracking the most popular author since Shakespeare through her least authoritative incarnations, can we work towards a more inclusive reception history. The immense range of formats and communities that participated in Jane Austen’s celebrity over the first two centuries of her literary afterlife has yet to be fully catalogued. There are many important Austen books worth collecting that never made it onto a t-shirt — or onto the shelves of the libraries that scholars tend to consult.

Janine Barchas is the Louann and Larry Temple Centennial Professor in English Literature at the University of Texas at Austin. Her new book The Lost Books of Jane Austen urges the value of cheap reprints to reception history.