We learned more from a three-minute record, baby, than we ever learned in school.

—Bruce Springsteen, “No Surrender”

Each year in the muggy cluster of days leading up to July 4th I am given occasion to become, it would seem, unreasonably furious. For each year at this particular time I am forced to revisit a pop song that I love, but one whose place in the national imagination is troubled. A song, dear reader, so consistently misapprehended, so clumsily handled and culturally battered, that I find myself, in some infernal backyard, beery, overhot, and ill-advised, yelling at someone whose name has surely already escaped me. There I am, over-familiar and too close, demanding: “listen…no, really listen!”

What follows is typically as impassioned as it is inarticulate; a regrettable too-human foray into the sudden and overwhelming need to be understood.

But now that the barbecue smoke has mostly cleared, in the dregs of winter, I want to ask — with all due politeness and grace — for you to listen.

It starts with a snare. A shotgun blast enshrouded in a boomy reverb: evergreen, capacious, loud. Then a bejeweled synth line, round and queasy, smugly confident, wet. And finally — as if from nothing and nowhere at all — rage.

“Born down in a dead man’s town / first kick I took was when I hit the ground.”

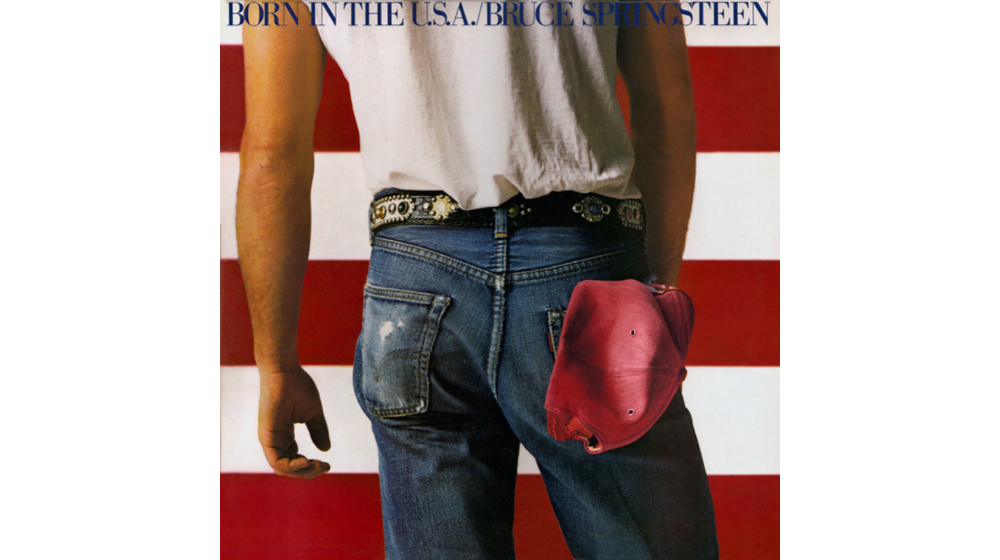

A political song, they say, ironically (perhaps even subversively) wrapped in the flag. Wolfish lyricism blasted through the sheep-herd populism of its chorus, a song that trades in confusion. Taken together, it all ventures a question: What is “Born in the U.S.A.”?

This is a particularly uninteresting question, though its attendant contradictions tell a familiar tale. Springsteen’s own hometown newspaper, the Asbury Park Press, wrote about it as recently as 2018, noting that “‘Born in the U.S.A.’ “has a complex history regarding the level of its patriotism.” Complex history may be generous. Still, it is a well-tuned narrative that involves the conservative Right’s inability or unwillingness to hear the truth of the song. Recall only briefly the stream of conservative pundits and politicians championing Bruce’s folksy charm, his anthemic revivals, his true-blue Americanness.

Greg Kot, in a 30-year retrospective of the song, details this history: “[George] Will, [Ronald] Reagan, and countless others never got past that big, seemingly uplifting chorus to figure out what the song was really about.” Springsteen, Kot admits, is partially to blame and suggests that “it takes a close reading of the song” to get to the real message. If Will and Reagan’s misapprehension in 1985 was a tragedy, then in our current moment, in so many nauseous and kaleidoscopic ways, it has surely become farce. In 2016 Slate ran the headline “Trump Becomes Millionth Right-Wing Creep to Misinterpret ‘Born in the USA’.” Two years before, The Daily Beast had asked “Are Politicians Too Dumb to Understand the Lyrics to ‘Born in the USA’?

This perennial question seems to serve as some ideological salve for the Left. The Right may have the Senate, they may have the Presidency, they may be dismantling the social field with a careful precision… at least we can read.

But the Right’s commitment to surface reading has never been especially interesting, and today it seems to be the least of anyone’s worries.

Besides, there is something cloyingly self-congratulatory and politically flaccid about this version of things. It looks like this: the true fans get the hidden Lefty message (apparently by, um, listening to it?) and the bumbling establishment hacks (lazy as they are) mistake irony for patriotism and go on beating their drums. This story is largely held up by the myth that a truer version of the song exists, one that more readily betrays its intent. Kot again: “Springsteen made sure to underline the song’s true message a decade later when he performed ‘Born in the U.S.A.’ as a bitter, bluesy dirge on a solo tour.”

The version Kot refers to was indeed performed a decade after release, but it was worked-up before, in 1982, while Springsteen was working on an album composed entirely of bitter bluesy dirges, Nebraska.

Bruce elected to release the vamped-up version we know today. Why?

“Born in the U.S.A.” is a song of audible rage, but this rage is entirely inseparable from its production, from its angular and glossy trappings. This tells us something not about the song’s politics, but the politics of a pop song; how these politics are asserted, and what they might mean. This means making a distinction between simply reading lyrics and hearing a song; it means thinking about production and form as operant makers of meaning.

Listen: that synth we all bemoan. It sounds along the same contours as Reagan’s false-tooth grin, his three-dollar haircut, his faux-everyman posture. It is begging to signal a shiny, happy American people. A chosen people. It is begging, we all so condescendingly register, a bit too much.

Listen: that snare drum five miles wide. The reverb doesn’t decay. It doesn’t act much like reverb at all. It holds its spaciousness like armed borders. It calls attention to its overmuch digitality; it feels like a false world because it is a false world. A veneer with absolutely nothing beneath.

Listen: the absolute unrelenting formal perfection of this song. The snare that announces the polished crystal of this sonic-world remains steady throughout, carving out the song’s progressive empty-time; but the kick-drum? The kick-drum waits. “…first kick I took was when I hit the ground.” Not until this “kick” does Max Weinberg kick. The lyrics are tethered precisely to the production and arrangement.

Pop music has always been a particular way into cultural memory. Springsteen is perhaps our nation’s most beloved or reviled — depending on your tastes — archivist of cultural sentiment. He trades in capital “O” Origins (Born to Run, Born in the U.S.A.), sepia-tinged mythmaking (Darkness on the Edge of Town; The Wild, the Innocent & the E-Street Shuffle), and pseudo-secular worship (The Rising, Magic). But he has always had a keen sense of how to render these in that saccharine and fast-acting genre of our time: the pop song. He remains committed to this form and its possibilities, however dilated or mutated they may become.

Another way of saying this is that Bruce Springsteen is a formalist. But you don’t need to be a terribly skilled dialectician to know that that admixture of form and content produces something in excess of itself. “Born in the U.S.A.” takes place, presumably, in its own present. That is, it is a song of 1985. But it is also a song, as so many commentators are ready to point out, about Vietnam.

This does not mean it is about the military blunder of a generation, about the bloody and servile mistake America has not stopped repeating. It is about this, sure. But it is about the endurance of history beyond these moments, and it is about our apparently endless willingness to forget them. That is, it is about how our history insistently impinges on our present, and how we, with a striking collective smugness, fail to acknowledge it.

Listen: “I had a brother at Khe San / fightin’ off the Viet Kong / they’re still there, he’s all gone…”

It would be easy enough to read this as a clumsy declaration of American failure. America, after all, lost. But the force of the line is tied to the fact that it fails to resolve, the second couplet sits heavy, awkward in the song’s ecology, a barren measure mapping out just what it means for something to be gone.

Listen: “10 years burnin’ down the road / nowhere to run, ain’t got nowhere to go”

The song insists on a ghostly temporal gap. 1985: we are 10 years on from the official withdrawal from Vietnam, and we have elected the Gipper. That snare drum is the sound of union busting. That overfull synth is the sound of wealth distribution gone uneven. You can hear the shattering of Glass-Steagall and a reinforced bulletproof glass ceiling.

Listen: Those bloviating drum sounds, those elastic bass lines: these are not irony, they are not hiding anything, they are staring us square in the face. This is the world painted red, these sounds are our inheritance. This song commands us to take it seriously. This is what it means to be born in the USA: the gas fires of the refinery, the shadows of the penitentiary, that still-encroaching darkness on the edge of town.

Listen: we are long past 10 years further down the road — hell, we are past 20. If we had nowhere to go in 1985, you can imagine the spatial arithmetic now. The darkness, the shadows, it seems, have long been closing in. But if I can prescribe anything for these times — some consolation for our collective horror — it is to go to a pop song and listen. These slight objects, in seeming so tawdry and cheap, are brimming over. Encyphered in that three-minute blast of melody and desire lay the dregs of a history that might torque our collective melancholy.

Republican misreadings are a dime a dozen; knowing this won’t make them stop. Bruce Springsteen isn’t a savior any more than Bruce Rauner is. But if we listen — really listen — we just might find new resources — ballasting, enlivening, full — to live in these times. A pop song doesn’t change history, but it can help you live in it.