Crossing I-35 into Mexico 54 in spring break of 2003, David Bowie in the background, it occurred to me that music could transcend sensorial experience. This was 31 years after Ellen Willis wrote a devastating piece for the New Yorker titled “Bowie’s Limitations” expressing her dissatisfaction that “Bowie doesn’t seem quite real. Real to me, that is — which in rock and roll is the only fantasy that counts.” She was right — Bowie didn’t particularly preoccupy himself with strict realism, and that’s exactly what gave depth to his craft. Willis’s angle of criticism looks at Bowie simply as a rock star, but Bowie, as we know, often transcends category. In some ways, his work can be better understood from a literary perspective, under the auspices of magical realism.

¤

Having grown up in Latin America with Gabriel García Márquez and Jorge Luis Borges, the themes found in magical realism and the genre itself are familiar. André Breton found Mexico to be “the most surrealist country in the world” after visiting in 1938. Indeed, surreal experiences are thought to be mundane in the region, which I suppose is what happens when death so closely enters the everyday. The culture’s organic fascination with the afterlife has been well documented. This can be seen more recently in what may easily be called a film of magical realism, Coco (2017), a tale about a Mexican kid who descends into the realm of the dead in search of his great-grandfather.

While Colombian Nobel Laureate Gabriel García Márquez and his One Hundred Years of Solitude are well known internationally, fewer know Juan Rulfo, a Mexican writer who heavily inspired the work. Susan Sontag called Rulfo’s novel, Pedro Páramo, “one of the masterpieces of 20th-century world literature,” and claims García Márquez could recite the book by heart. Rulfo believed literature could only be literature if it managed to alter reality, and found fiction to be more valuable than non-fiction precisely for this reason. “Reality has limits,” he said, “it must be sustained through imagination.”

¤

We were driving back home to Oaxaca, Mexico, after a family vacation to Texas. Dad, always too cautious with his music collection, kept only Greatest Hits or copies in the car. For the occasion, there were two of such compilations — The Best of Talking Heads and of David Bowie. In those years of teenage angst my dad’s music seemed antiquated to me, but the synchronicity between the turning of the car key and the countdown — “(five, four, three) check ignition and may God’s love be with you (two, one, liftoff)” — kept my then-favorite Britney Spears unplayed for the entire 18-hour drive, to the relief of everyone in the car. It was Bowie’s electric ability to launch the listener into his melodic universe that enchanted me.

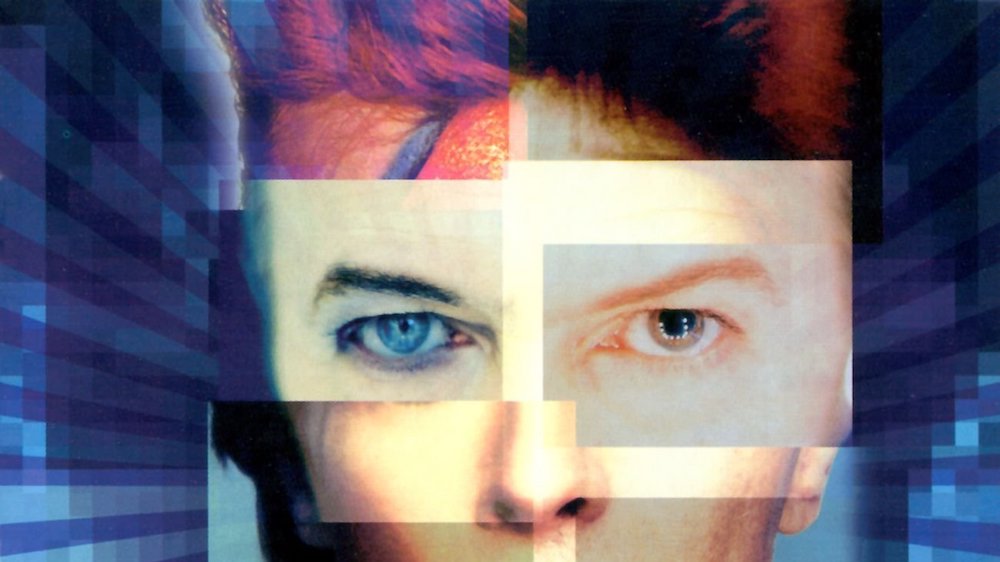

Once home I went back to my musical routine, but Major Tom’s desperate and claustrophobic guitar kept interrupting my thoughts. I asked dad who he’d played in the car, mentioning the guitar and another song with something about swimming like dolphins. “Bowie!” Bowie. I looked down into the plastic case that he placed in my hands: a distorted face with a piercing set of eyes stared back at me — one blue, one brown — radiating from a blue big bang. “Strange fascinations fascinate me.” Dad let me keep the CD.

Alone in my room as if to take part in a ritual, I set the disc inside my brand new lacquered red SONY player — as bright red as Bowie’s hair on the cover — and pressed play. With a desire to belong, I was back in Bowie’s world.

¤

Carried in dream-like prose, magical realism is characterized by emotions and a desire for freedom. In a world that echoes but isn’t strictly ours, we free our minds for more radical ideas. In fiction, people give themselves permission to explore eccentric versions of themselves and unprecedented possibilities for society. As such, the medium encourages subversive realities and underground heroes.

Since his early years, Bowie spoke to and of misfits, giving them a fictional space in which to exist and belong. In his album, “Space Oddity,” he sings about the “wild eyed boy from freecloud” who will be executed, as society has decided that there’s “madness in his eyes.” The boy cries on the eve of his death, “it’s really me, really you, and really me, it’s so hard for us to really be.” In his book We Could Be Heroes, music journalist Chris Welch quotes Bowie’s remarks on this song: “It was about the disassociated, the ones who feel as though they’re left outside, which was how I felt about me.”

Similar characters may also be found in pages of magical realism. García Márquez’s masterpiece, One Hundred Years of Solitude, is set in the fictional town of Macondo. Loosely constrained by time, it follows the town’s history from beginning to end through its founders, José Arcadio Buendía and his wife but also cousin Úrsula Iguarán, and their descendants. In his essay, Total Reality, Total Novel, Peruvian Nobel Laureate Mario Vargas Llosa notes that Macondo’s society is strictly patriarchal, and “man is master of the world, the woman mistress of the home in this feudal family.”

Úrsula lives to be well over a century-old as she refuses to die, and it is she who propels the family forward after her husband — lost in an eternal Monday — goes insane. To Vargas Llosa, “the real support, the backbone of the family is the small, active, tireless, magnificent Úrsula Iguarán.” Standing at the edge of society, disenfranchised characters like Úrsula or the wild eyed boy become either challengers or martyrs of the status quo. They transform into heroines or heroes within the fantasy of their realities, and softly into ours.

Vargas Llosa also writes that, as a work of magical realism, One Hundred Years of Solitude “narrates a two-dimensional world” where “the vertical (the time of its history) and the horizontal (the planes of reality)” make Macondo both “traditional and modern, provincial and universal, imaginative and realistic.” Similarly, Bowie orchestrated fictional worlds reflected from our own, directing their melodies as much as their aesthetics.

With “Space Oddity,” Bowie tapped into the anxiety that stemmed from the Cold War and the US space race against the Soviets. And he obsessively turned to alien realities, a fiction of his time, throughout his career. As society nervously waited to walk the moon, he made sure these steps were his in the public’s imagination. He gave life to Major Tom as he launched for space, as well as to the life forms that may already exist there: “[D]on’t be afraid of the man in the moon, because it’s only me,” he says in his self-titled debut album. Bowie contemplated the possibilities of life on Mars, the Starman who’d “like to come and meet us but he thinks he’d blow our minds,” and also a reality where Ziggy Stardust — his androgynous pansexual alien rockstar alter-ego — could actually descend to earth.

In magical realism there’s something known as “authorial reticence,” which is when the writer cannot be bothered to justify the fantasy they have created. The fiction is indifferent to what our reality finds abnormal, strange, or uncanny, and the lack of emphasis and explanation creates an appearance of normalcy. This reticence appears also in Bowie’s vague remarks regarding both his and Ziggy’s sexuality, and in his refusal to explain his transformations.

Through magical realism, Bowie’s craft challenged our assumptions. His songs punctured through the core of our reality, negotiating with the struggles of identity and sexuality, with the numbness of routine and monotony. Through his personas, lyrics, and melodies, he explored our desires, fears, and deepest apprehensions (“will you see that I’m scared and I’m lonely”). His characters were so strong, so distracting, that often the message went subtly by, perhaps into our subconscious.

¤

Throughout my teenage years, and into adulthood, I listened to Bowie religiously.

But it was only after his death that I realized my understanding of Bowie had been limited. I’d been mistaken to think of Bowie’s personas as simple theatrical performances, instead of as subversive characters through which we could explore different versions of our reality.

Bowie took all of his personas seriously, as well as their preoccupations, and as with magical realism, death was a recurring theme throughout his career. Covers are almost never better than the original, but Bowie’s take on Jacques Brel’s “La Mort” is an exception. He played the most stunning version of “My Death” in 1973, for his final performance as Ziggy Stardust with the Spiders of Mars. He was so invested in the song that he spends the first minute of it shushing the cheering crowd, at one point even fully pausing to ask that they “be quiet.” Then he goes on: “My death waits like a witch at night / As surely as our love is bright / Let’s not think of that or the passing time.”

Yet there’s a teleological aspect in Bowie’s vision of death that’s reassuring: he focused on life, where he explored all that can come from conquering love (“We can beat them, forever and ever. Oh, we can be heroes, just for one day”), earth, space, and time. This is comparable to what Mexican poet and Nobel Laureate, Octavio Paz, says of his country’s culture in The Labyrinth of Solitude, “Our cult of death is also a cult of life, in the same way that love is hunger for life and a longing for death.” In both “The Next Day” and “Blackstar,” Bowie faced death like a tidal wave. And he did it so smoothly — having had trained us for so long with his magical realism, none of us noticed.

Through fiction, Bowie eased our fears, inviting us into magical realities, if we only managed to believe in the alien who fell into earth, the insane lad who lives in the fringes of society, or The Thin White Duke. Willis adored Hunky Dory, but could not grasp that Bowie existed within all his kingdoms as separate, yet bound together through us. While to Willis rock and roll obeys only to the fantasy of realism, Bowie displayed nothing but disdain for the rock and roll canon, even warning, in Hunky Dory’s anthem, “Changes”: “Look out you rock ‘n’ rollers, pretty soon you’re gonna get older.” Bowie embodied change. He metamorphosed because that is the nature of life. He knew personalities are fluid —like time in Macondo — so why would we expect the same from his music?

Much in the same way that García Márquez creates and destroys Macondo, Bowie built worlds for Ziggy Stardust and Major Tom only to bring them down. Vargas Llosa finds One Hundred Years of Solitude to be whole and self-sufficient because it, “depletes a world” — the “reality described has a beginning and an end.” It rises and it falls. In his last opus, Bowie was just a man. For his last persona, Bowie chose to be Bowie.