It is a rainy day in Vienna when I escape into the warmth and dryness of Café Sperl for my planned assignation with Rainer Maria Rilke. Making plans with dead authors is easy — I can meet with them at the time and place of my choosing, as long as I have my book in tow. For my meeting with Rilke, I resisted buying a book at the bookstore where I work, and instead sought one out in Vienna as a memento of my visit.

I visited Shakespeare & Company on a small side street in the Innere Stadt, and scoured their stacks in search of a copy of Letters to a Young Poet. I instead found one of the Everyman’s Library Pocket Poets series, of which I’ve amassed a small collection, and which granted me access not only to the specific text I had intended, but also to a broader assemblage of Rilke’s work.

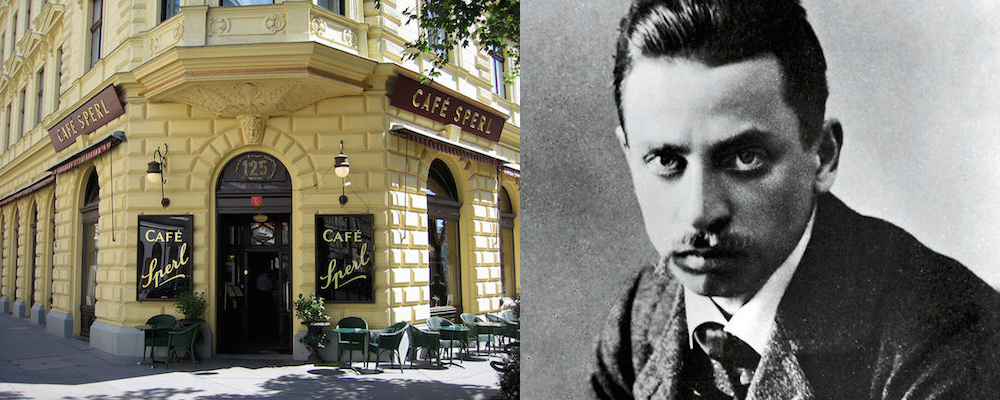

Rilke spent more of his time south of Vienna, where he received military training as a boy at Wiener-Neustadt. It is that military academy that led to the correspondence that makes up Letters to a Young Poet. Vienna was the nearest I could get to the military academy that connected Rilke and Franz Xaver Kappus, the titular young poet. I chose Café Sperl as a place that existed during Rilke’s time there, and as one he may have visited when coming into Vienna during his years at the academy. I can imagine him having a coffee and a break here while stationed at the War Archive in Vienna during World War I, several years after his correspondence with Kappus concludes. Café Sperl claims it was popular with both the artistic and military crowds during WWI, so Rilke would have been at home as both an artist and a conscripted member of the Austrian military.

It is easy to feel like Rilke and I are in conversation, when his letters are full of advice, answering questions posed by Kappus. I hang on every word as I sip my “Grandma Coffee” (a double mocha, since I’m on vacation and wanted something more exciting than my usual drip coffee) and read, envisioning him sitting across from me at my small table. His words are with me, and so, therefore, is he.

Café Sperl gained fame in the 1990s thanks to its appearance in Richard Linklater’s Before Sunrise, but it hails from the 19th century, and for me, was the perfect place to connect with Rilke. It was quiet on the morning I visited, and I found myself under the care of a waitress who did not have many other responsibilities. She left me to my own devices once I had received the coffee I ordered and its accompanying biscuit, allowing me quiet time alone with Rilke. I sat next to a window, watching the few people out wandering in the rain as they splashed through puddles next to curbs and kept their umbrellas up to protect themselves.

The café itself looked largely unchanged over the more than 130 years it has been in operation. The walls were wood-paneled and the seats covered in red brocade, with padded benches lining the walls, creating an inviting and old-fashioned setting to spend a few hours. In the middle of the room was a large table covered with newspapers, encouraging patrons to stay and read a while.

I came to the Letters to a Young Poet with no specific questions in mind for Rilke to answer. I wanted his wisdom to wash over me and respond to questions within me that I had not yet known to ask. It was a great comfort to be alone in a new-to-me city with a book full of wisdom and beauty to be my friend as I explored on my own.

As Rilke wrote, “Do not search now for the answers which cannot be given you because you could not live them. It is a matter of living everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, one distant day live right into the answer.” It felt like a perfect encouragement to me to come to his texts with an open mind and choosing to “live the questions.”

It is so easy to imagine Rilke, looking somber and angular the way he does on so many book jackets, seated across from me, making this visit to Vienna into a literary pilgrimage. When I travel alone, I am often too shy to strike up many conversations with locals. This may be a surprise to those who know me and see the facility with which I provide customer service or meet new people, but when in a strange place, I tend to take the opportunity to retreat into myself a bit. It makes for a rich internal life — hours spent reading, writing, or just watching — but it means I miss out on the connection with locals that feels so important to me as a part of traveling.

Being with Rilke was like befriending a very wise local who wanted to teach me how to live, and how to make my trip to Vienna worthwhile:

Try to raise the submerged sensations of that distant past; your personality will grow stronger, your solitude will extend itself and will become a twilit dwelling which the noise of others passes by in the distance. — And if from this turning inwards, from this sinking into your private world, there come verses, you will not think to ask anyone whether they are good verses.

This passage of Rilke’s came to me as a blessing that my inward concentration could have a purpose. That it could make me a better writer to have a distilled sense of self, and that sitting alone in cafés thinking and writing would lead me to not only better writing but a stronger self-assurance in what I write.

Rilke continued to provide encouragement regarding my chosen solitude. “And to speak again of solitude, it becomes increasingly clear that this is fundamentally not something that we can choose or reject. We are solitary.” So, perhaps the solitude of my trip to Vienna was not so much chosen as it was inherent, and indicative of a larger tendency toward human solitude, which Rilke so aptly describes.

I found, in Rilke’s work, words that not only consoled and encouraged me as a writer and a solo traveler, but words that reassured me as a woman in a complicated world, rife with pain. Amidst countless recent stories of the harassment and assault that most women I know have endured and spoken of in recent days, bringing to light years worth of pain and frustration, Rilke writes:

The humanity of woman, brought forth in pains and degradations, will come to light when she has shed the conventions of mere femininity in the alterations of her outward station, and the men who today do not feel it coming will be surprised and struck by it… This step forward will (very much against the wishes of outstripped man to begin with) change the love experience that now is full of error, alter it to be between one human being and another no longer between man and wife.

His vision of fully realized women, with men “surprised and struck” by their new roles and found voices, feels prescient for today. He could not know how much that promise of inevitability would mean to me, nor how frustrating it would be that a century after he wrote those words, change is still so slow in coming.

Though it should feel like I am eavesdropping as Rilke provides wisdom for Kappus — and in a café, that image resonates even more — instead it feels as though Rilke is speaking directly to me. That is the appeal that so many people have found in this book — Rilke’s wisdom is universal, and intended for a wider audience than that of just one young writer. Thank goodness Kappus made his letters available to us all.

I slowly drink my coffee, unwilling to say goodbye to this moment. I do not want to leave the warmth of Café Sperl, and I do not want to conclude the conversation I am having with the ghost of Rilke who has become, for a brief moment, a travel companion and mentor. The rain begins to let up as I reach the bottom of my cup. I tuck Rilke’s words into my bag and prepare to step outside, still trailed by his ghost, as his wisdom echoes in my mind. I do not leave him behind, but instead take him with me as I set off to explore more of Vienna, alone, with only his letters to keep me company.