MASTERS OF SEX, “PILOT”

Dear Television,

BEFORE WE GO any further in discussing the pilot of Showtime’s new drama, Masters of Sex, I want to take one more look at its title. I’m in full agreement with Phil: Michelle Ashford’s show about the famous team of sexperts — William H. Masters and Virginia Johnson — could not be more unfortunately named. (Lizzy Caplan, who portrays Johnson, is of the same opinion.) If we’re not embarrassed about its bold declaration, we should at least be embarrassed about the bad punning. Whether in 1956, when the show begins, or this past Sunday, right on the heels of TV’s morally dubious journey with Walter White — sex is a topic that apparently remains scandalous. Just to see the word in a title is enough to give us pause. What’s particular about the implication in Masters of Sex, though, is that while we might be liberated (and liberal) enough now to embrace the fact of sex, to know too much about sex still seems undesirable — even prudish.

When we debated covering Masters of Sex earlier this summer, someone made the joke that it seemed especially “on brand” for us. And if we follow the general critical reception on the show so far, we might take “on brand” to mean something like “best new show of the fall season.” I’m being facetious (quite like the show’s title!), but judgments such as “best new show” are of course culturally weighted. While we did anticipate that Masters of Sex might keep company with current prestige dramas (it does star Sheen and Caplan and it does, after all, air immediately after Homeland), we weren’t sure — having not, well, seen the show — exactly in which ways it would. And even now, while its first half-dozen episodes have been largely embraced and vouched for by critics, there’s still a general sense that no one is quite sure what Masters of Sex is doing — in terms of pacing, plotting, tone — and that this ambivalence itself is, if not a definite good thing, at least refreshing.

This brings us to the difficulties of judging pilots in isolation. Even comedies, more fixed in their repetitious episodic formulas and rhythms, are often spoken of as getting better or gaining momentum across time (cf. New Girl, Parks and Rec). The buzz that has already surrounded Masters of Sex as The Show To Watch makes me wonder if even Mad Men garnered this much talk leading up to its pilot. Then again, Mad Men seems born of another era of TV viewership and criticism.

Masters of Sex opens just four years prior to when the Mad Men pilot takes place — and most criticism about the show so far hasn’t been able to discuss the former without reference to the latter — a move that is beginning to feel more and more reflexive. The comparisons between the two period pieces, though, have been mostly made in order to stage the difference between the two. To repeat Phil:

Masters of Sex is not, in other words, a Mad Men rip-off, and the longer we talk about them in the same breath the more difficult it will be for an audience to build around the new series. But looking especially at this first episode in the context of Mad Men’s, I think we can figure out a little bit about what makes this pilot feel slightly off, and also what makes this pilot thrillingly unique.

For starters, I think it’s a little premature to be describing Sheen as a male anti-hero (and perhaps it’s time to reevaluate that term in general — anti-heros have been around since Don Juan, and it also doesn’t mean Male Character That Is Both Awful And Sympathetic, because oh my god is that list long). Sheen is neither as aggressively charming nor self-loathing as Don Draper (yet), and his reservation is seen as part of his charm. (I, for one, have always found Michael Sheen more compelling than Jon Hamm.) Though questions such as whether Caplan’s vivacious portrayal of the competent Johnson will accrue the complexity of a Peggy Olson seems a strange comparison, since what drew Peggy and Don into the possibility of becoming equals was that their relationship was never an explicitly sexual one. The wilting and repressed housewife figure is not to be missed, though. How much is Sheen’s wife — portrayed in an almost classic melodramatic tenor by an exquisite Caitlin Fitzgerald (who is dating Sheen in real life) — like a more sympathetic Betty Draper? Opinions about the actors, beyond noting how attractive and dapper everyone is, are generally laudatory. Sheen and Caplan are both seen as playing somewhat outside of their usual register of characters — both eschewing irony or comedic archetypes for more earnest performances.

Masters of Sex is a show that isn’t afraid of spoilers, especially given that most of its main events can be found on a Wikipedia page. In fact, it’s a show that seems almost flagrantly dismissive of the plot conventions that come with creating the suspense or surprise that builds during the will-they-won’t-they proceedings of most drama romances (even if we know that 95% of the time they will). Masters of Sex is almost pat with its use of cuts: after the opening scene where Masters excuses himself from his own honoring party, we go to a shot of a man (face, at first, obscured) going at a woman from behind. It’s only after this shot that we clearly see that Masters is not the one having sex, but is instead observing it. Later when Betty DiMello (played by Annaleigh Ashford), the prostitute who’s helping Masters conduct experiments, tells him that he needs to get a “female partner” if he truly wants to study it, the camera jumps to another scene where Ethan Haas (Nicholas D’Agosto) is describing the new attractive secretary (Caplan’s Johnson) to Masters. It doesn’t expect much work from the viewer to put two and two together, and these logical connections are displayed to us early on perhaps in order to do away with their importance.

This is where Phil’s discussion of the weird pilot might apply (and others, such as Andy Greenwald and Alyssa Rosenberg, have noted the rushed pacing of the show as well). Plot points are so hurried in the pilot that critics have expressed concern at how well the show might sustain itself in the long run (insert plateau joke here). Greenwald has suggested that, at this rate, Masters of Sex might fall into the unarresting narrative circuitry of another history-influenced show, Boardwalk Empire.

Unlike Boardwalk Empire though, or Mad Men for that matter, Masters of Sex has less vitriol for its characters — it doesn’t seem to want to torture them by sending them through the same plots or psychological traps. If anything, Ashford imbues her characters with almost achronological flashes of boldness and aggression. (Its soundtrack takes risks — some more successful than others — with almost jarringly contemporary and lyric-laden music.) We’re watching the 1950s from 2013, but there’s a great deal of the show that feels like it’s knowingly (and playfully) responding to a 2013 audience. The collapse of modern sensibilities with the quirks of 1950s pre-feminism gives a certain vantage — you might even call atmosphere — to Masters of Sex. And the sexually-liberated, modern, and frank Virginia Johnson is even more so when portrayed by Lizzy Caplan. It’s an odd mix, but the noted coyness of such directorial and casting decisions doesn’t seem to poke fun at its characters, actors, or viewers either. For one, play seems more consensual. The oppressed or stagnant atmosphere that can often plague period pieces (Downton Abbey, anyone?) is one that Masters of Sex has so far eluded. Perhaps it’s by virtue of, as Phil described, Ashford’s choice to tell more than show, that allows viewers greater space to choose how they see this particular story.

The subject of inquiry — the scandal at the heart of this new drama — might be sex, but even as evinced in the pilot, sex manifests itself (in life and on television) in a panoply of forms and scenarios, each effected by a complex array of motivations (even if part of the motivation is to not give this motivation much cognitive weight). Sex both is and isn’t easy to generalize. The show does not denaturalize or deglamorize sex — or it doesn’t do so consistently. It shows us various scenes of lovemaking with couples we have varied levels of investment and interest in. Some are played for laughs (“Good for you,” Betty says, after her first partner comes), while others, such as the scene between Masters’s first consenting experimental couple — contain very attractive individuals, but emphasize that this is for their pleasure as much as it is for the viewer’s. These scenes want to have it both ways — as the couple gets lost in their own ecstatic enjoyment, I’m not sure we always follow suit.

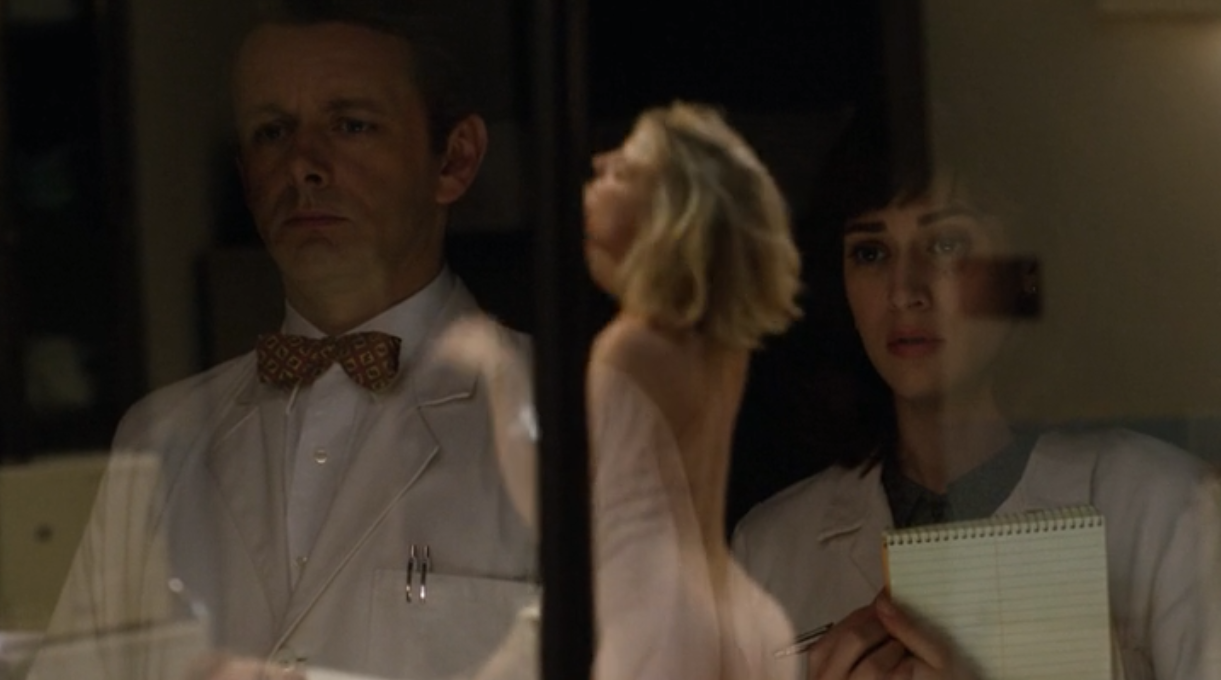

If anything, we grow closer to the couple at the heart of this show, which brings us back to the earnestness — the classic drama-ness of this show. Watching this experimental couple have sex (in the name of science!) is also to watch Masters and Johnson watch a couple have sex (the two leads are never outside our purview in this scene: Sheen and Caplan, or their reflections, are markedly present throughout) and as we might expect from the episode’s cutting patterns, this scene sonically and thematically overlaps with the next (and closing) one with Masters describing the dangers of transference in their experiments:

I have one concern about the possibility of sexual transference between us and our patients. We’re going to be watching them have sex and those couples know we’re watching them, and the likelihood of us transferring all this libidinous energy onto our patients is high.

Johnson asks if this is something he’s been having trouble with; Masters replies no, but that he already sees the beginnings of it in her interactions with male patients. Freud would have diagnosed this retort as projection. Masters and Johnson might have aimed to debunk Freud, but it’s unlikely any contemporary viewer of the show can watch it without Freud’s heavy and pervasive influence. Still, as viewers, our interaction with Masters of Sex might not need be quite so overdetermined. The pilot might have been uneven and oddly paced, but this has only helped sustain my curiosity (call it prurience even) in the show.

Jane

¤