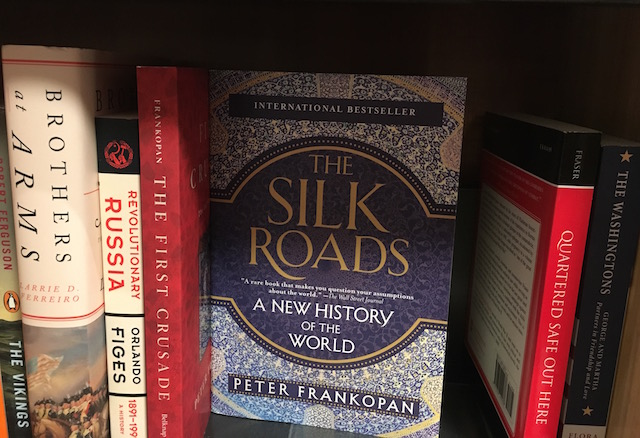

Oxford historian Peter Frankopan’s much-praised book The Silk Roads: A New History of the World, first published in the UK in 2015 and just out in paperback in the United States, is already available in various languages other than English and is getting reviewed and talked about in the press on several continents. One tangible indication of its reach is that, when I flew home from the Shanghai International Literary Festival Sunday, one of the last things I saw in China was a Chinese language edition of it displayed in a Pudong airport shop, while one of the first things I saw once back in America, as the photograph accompanying this interview shows, was the English language edition prominently featured on the shelves of an SFO bookstore. Silk Roads is a sprawling, engagingly written, comprehensive effort to pull the loci of world history east to the networks of political, economic and cultural exchange that have connected Europe with Asia for centuries. For Frankopan, these early trading routes form the basis for understanding the geopolitics of our time. I caught up with him via email to quiz him on various things relating to the present as well as the past.

JEFFREY WASSERSTROM: You refer to the silk roads, in the plural, in your book. What are the implications of using the plural?

PETER FRANKOPAN: The term “the Silk Roads” — in the plural — was coined in the late 19th century by the German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen. So using the term in the plural is not only appropriate, but also accurate: the term was used to describe intensive connections that connect across the spine of Asia. Reducing it to a singular “road” is problematic for lots of reasons, not least since it implies start and finish points and also [the existence of] a single route that has one course. It also conjures up long-distances — for trade; travel and exchange. That is all wrong. Most exchange was intensive and local. Goods flowed in all directions, not just east-west, but west-east and north-south and south-north.

I think that also reflects on the “Silk Roads” of history: the label is one designed to explain and capture an abstract set of connections. So assessing the history and the past of these connections requires a lightness of touch to ensure we are not creating and framing events, peoples, regions in a structure that does not reflect reality.

Are the same mix of countries involved or invoked in Xi’s One Belt, One Road vision, or does it seem to suggest a quite different geographical reach?

Xi’s vision has been very extensive — almost to the point of being open-ended. From a modern perspective, that could be seen to reflect smart-thinking, a drive towards inclusivity or an expansive foreign policy. Of course, it could also reflect the fact that the OBOR is in its early stages, so its priorities, geographical reach, aims and objectives are still being defined. When we read about trains and containers reaching the UK in January this year, many felt that this is the first moment of such long-distance exchange. As a historian, though, I’d point out that one see influences and connections between the Mongol world of Central and Eastern Asia with the British Isles 750 ago when a bishop was sent from western China to England and met the king, or seven centuries ago when the opening of a tournament in Cheapside in London saw English knights dress up as Mongol warriors. So the extensive vision and reach has some basis in the past too. Of course, today’s great difference is the speed of connections — by sea, airand digital too.

It’s always tricky to ask an author of a recent book to point readers to those by others, but if you had to flag two works by other people published in the last decade that would be particularly helpful in pondering these sorts of questions, what would they be?

I’d single out books by Valerie Hansen, Frances Wood and Xinru Liu — all first class scholars, and wonderful writers, too.

Do you have some favorite others book, new or old, to bring to our readers’ attention?

I have quite omnivorous tastes, so I read a lot about different topics, but I’m always trying to find and keep a look out for connections. I’ve been reading Pankaj Mishra’s Age of Anger as well as Chris de Bellaigue on The Islamic Enlightenment. An author I return to a lot is Zhang Qian who wrote more than 2000 years ago. I like to remind myself of other commentators in the past who have tried to understand the world around them. And reading the works of those writing 1000, 5000, or 1000 years ago is the thing I like best about being a historian.

Circling back to the present, are you hopeful, skeptical, a bit of both, or completely on the fence about the prospects for the OBOR plan bringing the benefits to China and other countries that Xi Jinping and company insist it will?

There is no doubting the ambition, the resources or the vision. Everything rests on the execution of the OBOR plan as a whole, and of individual projects specifically. It is inevitable that some ideas will be more successful and deliver better results than others. What matters is how the process of evaluation works, and how lessons are learned when things do not go according to plan, or even go wrong. We are living in an age which feels — and is — fragile, with much scope for volatility, disruption and confrontation. There are many elements of OBOR that promise stability and growth, both within China and in OBOR countries. Like a doctor, I spend a lot of time looking carefully at the tell-tale signs. Having an early warning system for problems— and also for resounding success — is what matters.