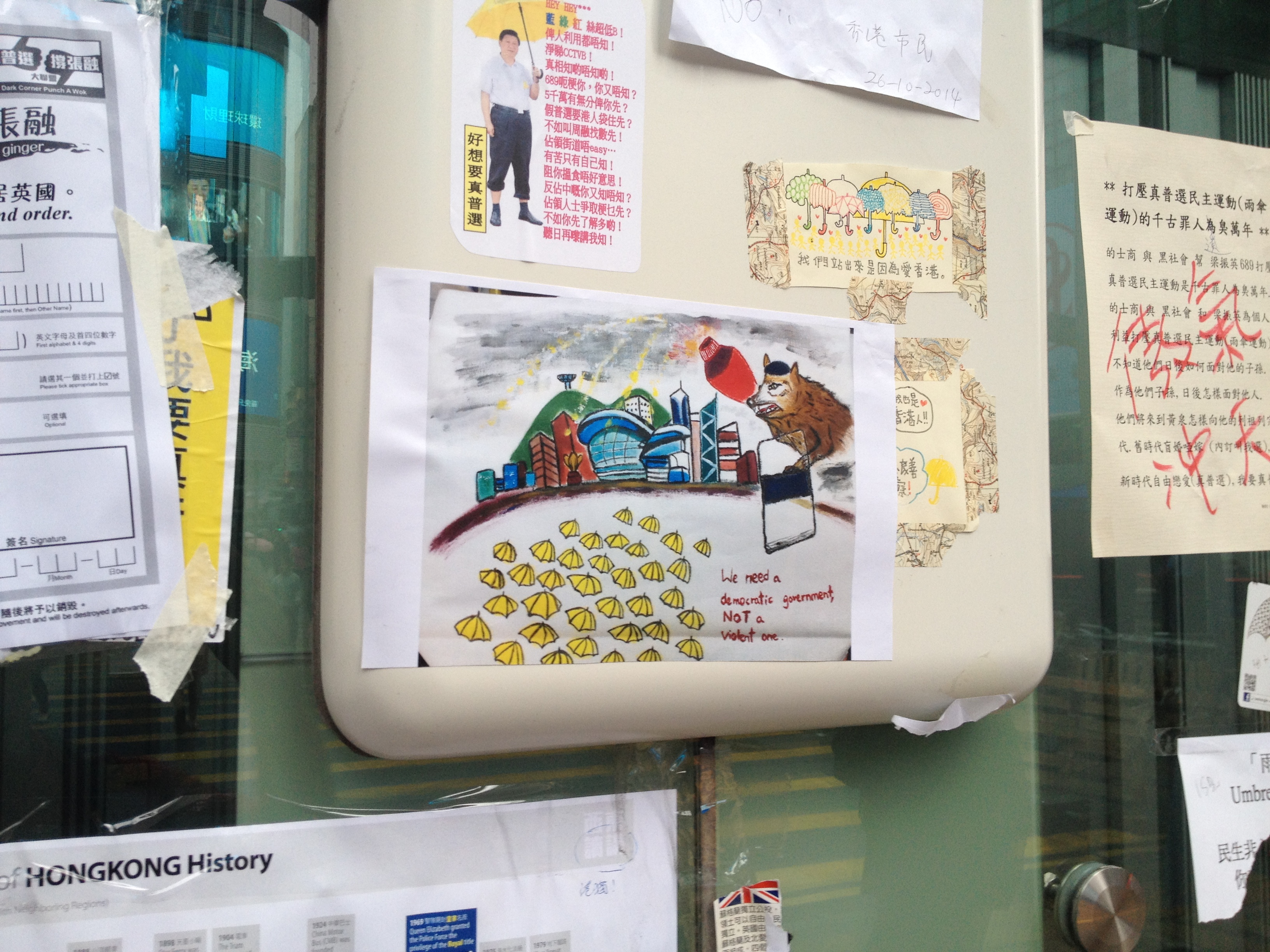

Note: All photos were taken in Mong Kok on the morning of November 8. The drawing in the center shows Hong Kong’s widely disliked Chief Executive C.Y. Leung, derided by critics as “The Wolf,” threatening protesters, represented by the movement’s iconic yellow umbrellas, and has a caption reading: “We need a democratic government NOT a violent one.”

There are many obvious differences between the headline-making events associated with Hong Kong and Ferguson. Let’s begin with a basic fact: there have been injuries but no deaths linked to the Umbrella Movement. In addition, while protests have erupted both on Hong Kong Island itself and across the harbor in Kowloon, there have been no actions in even the nearest mainland cities, such as Guangzhou and Shenzhen. This contrasts sharply with the situation in the United States, where demonstrations broke out from Los Angeles to New York City to express outrage over the Grand Jury’s verdict not to put the Ferguson police officer responsible for Michael Brown’s death on trial.

Still, the Hong Kong and Ferguson stories have become entwined in my mind, partly because, when checking my Twitter feed in recent weeks, I’ve often seen tweets about one place following tweets about the other. The most recent time this happened was on November 24, when the Grand Jury’s decision was announced just as news came of Hong Kong police officers using force to disperse the camp that protesters had set up in Kowloon’s Mong Kok neighborhood. By mid-week, while there were still sporadic nighttime marches in Mong Kok, which protesters described tongue-in-cheek as spontaneous “shopping” expeditions, the Admiralty area in Hong Kong Island’s financial district was left as the sole remaining major locale of non-stop protests.

Many either saw the November 24 developments in Missouri and Mong Kok as unrelated or tied together only by a fluke of timing. To me, though, there was a curious connecting thread — relating to, of all things, a pair of special libraries, one of which became more famous last week, while the other disappeared forever.

The library that became better known was, of course, Ferguson’s. In the wake of the Grand Jury’s announcement, while many local institutions, including the city’s schools, were closing in anticipation of disorder, it stayed open. And more than that, its sole librarian decided to expand the role that the library had begun playing as a safe haven for people looking for a place to do anything from spend time looking at books with their families to holding small meetings. When word of his actions spread, via news stories and a Q & A he did for the popular site Reddit, donations of money and books poured in.

Like many other people—and perhaps more than some, due to how important libraries are to me in my work and the fact that I’m married to a librarian — I find the story of the Ferguson Library heartwarming. There’s a bittersweet side to it for me, though, due to knowing how its rise coincided with the fall of another library that, for a time, had also served an important community-affirming function. I mean the one set up by protesters at Mong Kok that I wrote about in some details in a work of reportage titled “Hong Kong Visions”, which was based on visits I made to camps on both side of Hong Kong’s harbor early last month.

I devoted a good deal of that earlier piece to describing the Mong Kok Community Library and my interactions with a young couple, one studying social work at college and the other still in high school, who helped to tend it. I won’t cover the same ground here, but I only included two images of that short-lived library in “Hong Kong Visions,” which was published while the book repository and gathering place was still in existence. So it seems fitting to end this post by memorializing it in two ways. First, by offering up a few more photographs I took of the now vanished site. And second, by providing the wording of the new ending for “Hong Kong Visions” that I wrote last week for the Italian translation of that piece that has just been published in the magazine Internazionale — wording that I came up with after Junko Terao, their Asia Editor, asked me to find a way to bring in the clearing of the Mong Kok encampment.

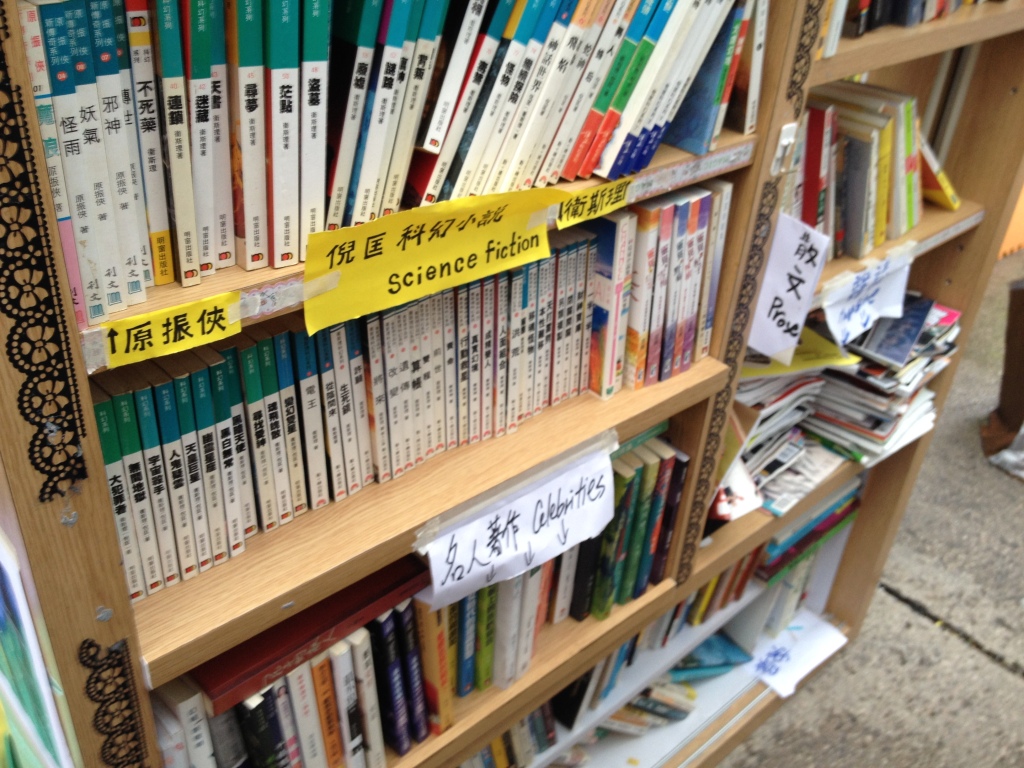

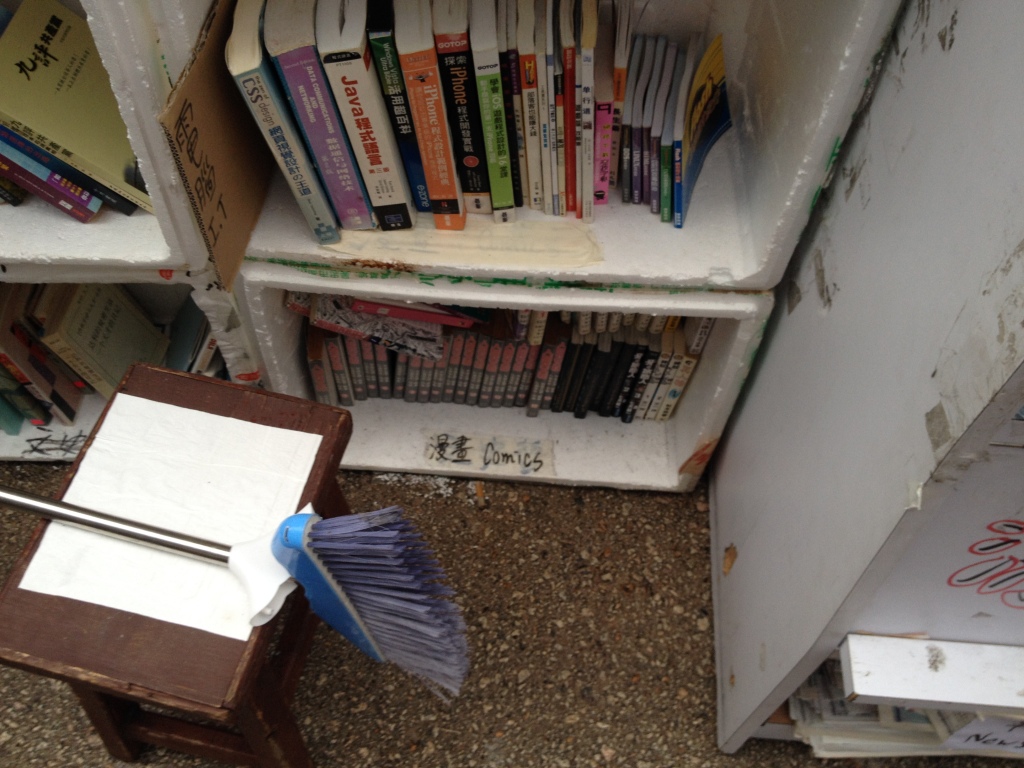

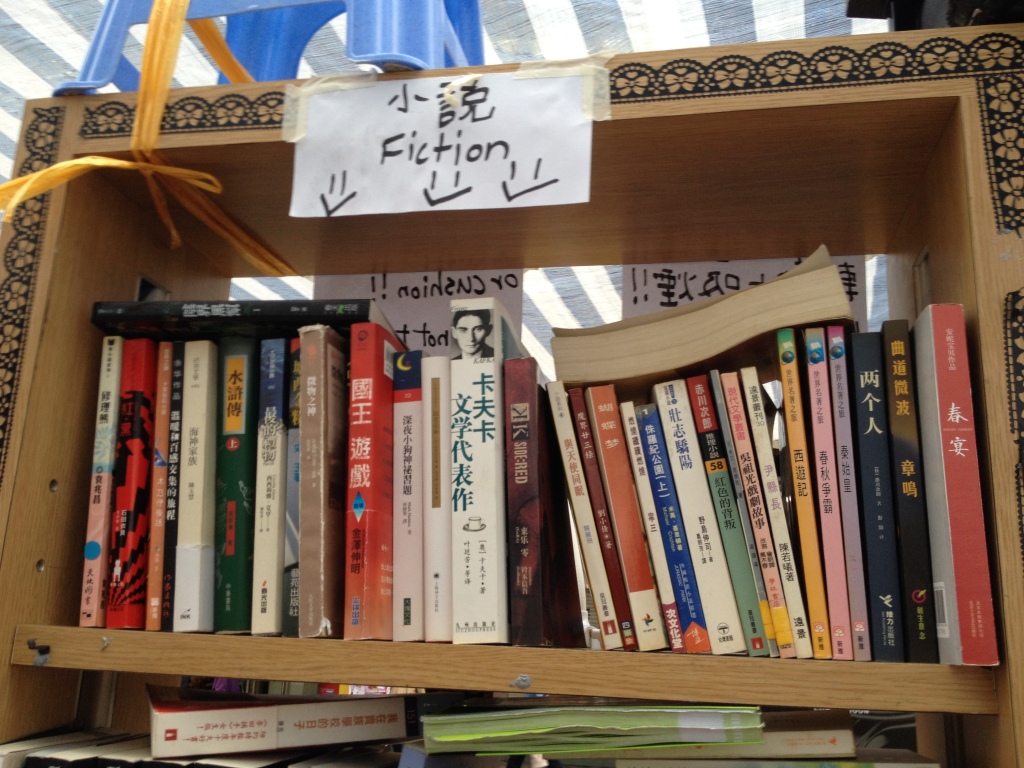

Here, then, are the photographs, which show, in turn, the shelves devoted to “Science Fiction” and “Celebrities”; “I.T.” and “Comics”; and “Fiction”—where a book by or perhaps about Franz Kafka shares space with, among other works, translations of The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-time and Jurassic Park, as well as editions of two enduring popular Chinese classic novels that feature rebels: Outlaws of the Marsh, a tale of Robin Hood-like bandits, and The Journey to the West, which tells the story of the mischievous Monkey King.

And here is the updated ending I wrote for Internazionale, to run right after describing my conversation with the young couple, who had been sleeping on the streets and encouraging protesters and passersby to stop and read the books on offer:

After saying goodbye to these two likable youths and leaving the protest zone, I felt very glad that I’d made the visit to Mong Kok and seen its special Community Library. Since returning to the United States, they are the protesters I’ve found myself most eager to tell people about. Though neither played a leading role in the movement, their tentatively smiling faces have become, for me, the faces of the movement. Following coverage from afar this week as police moved in on the Mong Kok site, I have kept scanning shots of retreating crowds in hopes of catching a glimpse of them. I keep wondering what has happened to them–and to the comic books, computer manuals, books about democracy, and collection of works by Kafka that were part of the special library they tended.”