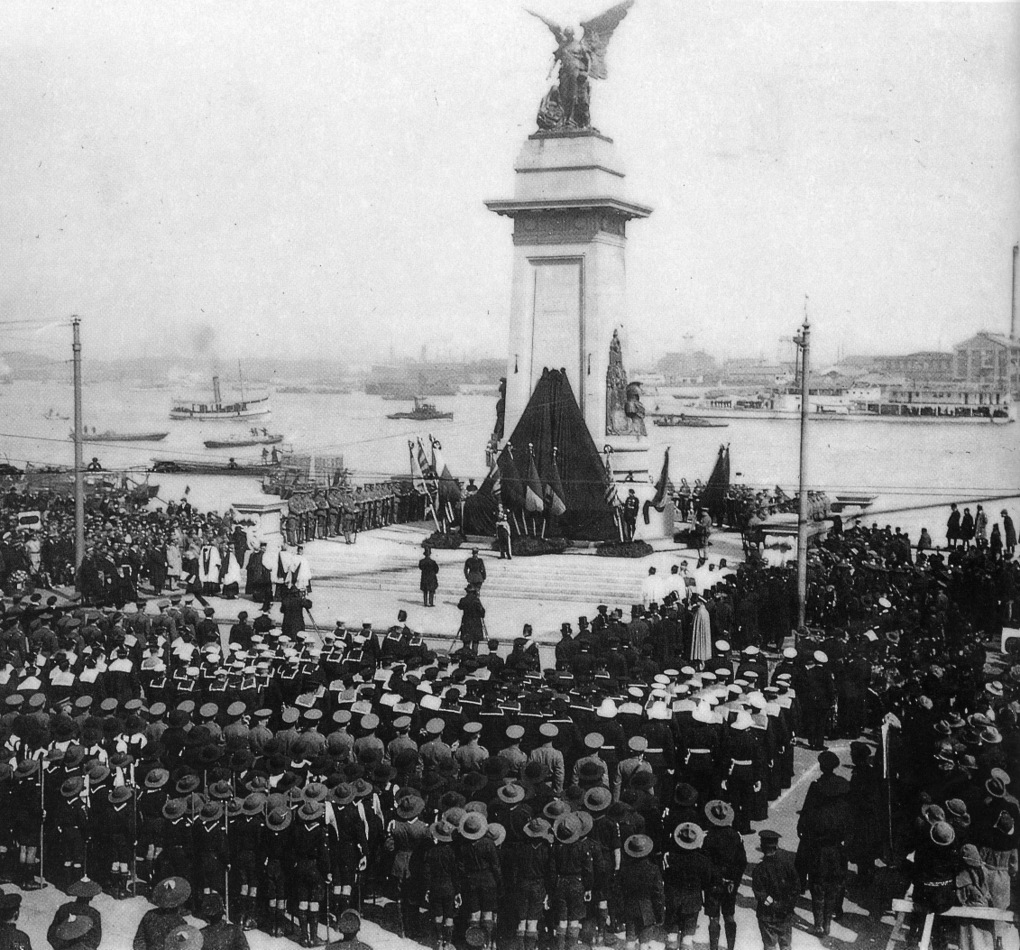

Photo: The dedication of the WWI memorial in Shanghai, in 1924.

World War I has always been primarily associated with Europe. That’s where the conflict began, where the major battles took place, and where the war had its most visible effect – the map of the continent was redrawn in its aftermath. But with the one hundredth anniversary of the war’s outbreak being commemorated this summer, we’re seeing more attention being paid to how non-European countries figured into “the war to end all wars.” Delhi-based writer Chandrahas Choudhury, for example, discusses India’s involvement in World War I in this Bloomberg View article, and The Guardian produced a documentary detailing the global nature of the conflict, though it’s still fairly Euro-centric.

China, too, became entangled in the fight in many different ways, and Penguin China is releasing a series of short “specials” that each focus on a specific aspect of China’s World War I history. These brief introductions (just about 100 pages), written by experienced journalists and historians, are available in Kindle editions and offer readers a quick overview of their subject matter.

I received review copies of four books in this series from Penguin China (there are two more titles scheduled for publication at the end of August) and arranged them in chronological order before I started reading. I began with The Siege of Tsingtao, in which journalist Jonathan Fenby recounts the story of the war’s only battle fought in East Asia, which took place in the fall of 1914. Tsingtao (now rendered as Qingdao, though the city’s famous beer retains the old spelling) was Germany’s main territorial holding in China and its base of naval operations in East Asia. Japan had long desired to expand its possessions in China, so it teamed up with Britain to attack the German port almost immediately after war was declared in Europe. Qingdao’s defenders never had a chance of keeping the settlement in German hands: they had few men and no supply lines. Though the Japanese and British forces were slowed down by heavy rains, they prevailed and took control of Qingdao by mid-November. Japan immediately moved to assert itself as the settlement’s new authority; its territorial ambitions in China would have long-reaching consequences.

The next book, Getting Stuck in for Shanghai, written by University of Bristol historian Robert Bickers, stays in the early days of the war, but moves down the Chinese coast from Qingdao to Shanghai. Although Germany didn’t hold any territory in Shanghai’s foreign concessions, Germans and British in the city routinely went into business together and shared social activities; there were even German members of the Shanghai Municipal Council, the ruling body of the British-American International Concession. As Bickers puts it, “Ethos and practicality made the business of coming to hate each other in the heat of 1914 not only difficult to fathom, but awkward to enact.” (Even that Tsingtao Beer was a product of the Anglo-German Brewery Company—British owners, German recipe.) But the British in Shanghai were patriots (even those who had been born in the city and rarely seen their “home” country), and over a hundred of them sailed for Europe in October 1914 to join the fight. Bickers follows the men of Shanghai to the trenches of Europe, where some died and more were injured, their fates recorded by the North-China Daily News so British readers in China could keep up with their countrymen.

Some of those trenches were dug by the 135,000 Chinese laborers sent to Europe beginning in 1916, who formed a crucial support team for the British and French armies. Journalist Mark O’Neill details their story in The Chinese Labour Corps, explaining how the British and French came to recruit tens of thousands of farmers—most from Shandong Province, the area around Qingdao—and send them by boat and train to the front in Belgium and France. Because China was neutral for most of the war, the laborers were hired by private contractors and specifically excluded from performing military duties, though many of them got much closer than they expected to the battlefield. As O’Neill explains, racism was rife: Europeans admired how hard the Chinese laborers worked, but treated them as slaves or prisoners, not employees with contractually guaranteed rights. Every man had to wear a numbered identification bracelet from the moment he entered the Corps until the day he was released, and they were crammed together in ships’ holds rather than given berths during the long trip to Europe. At the same time, participation in the Chinese Labour Corps offered many workers the chance to obtain a basic education through one of the work-study programs set up for them in Europe, as well as save money to send home to their families. Some laborers remained in France after their service ended, while most returned to China, their time in Europe quickly fading into memory.

Chinese leaders hoped that by encouraging laborers to join the Allied cause, they would earn some bargaining chips when the peace treaty was drawn up—but as occasional LARB China Blog contributor Paul French explains in Betrayal in Paris, this faith was misplaced. The nascent Chinese republic was eager to renegotiate the “unequal treaties” of the nineteenth century, which had enabled Western countries to set up extraterritorial enclaves throughout the country, and to fend off the encroaching Japanese empire. Chinese diplomats traveled to Paris for the treaty negotiations, optimistic that they had secured a seat at the table. At first, things seemed to go well: the leader of the Chinese delegation, Columbia-educated Wellington Koo, cozied up to Woodrow Wilson and thought he had the American president on his side. When Japan demanded that it receive all of the Shandong Peninsula, Koo delivered an impassioned but meticulous rebuttal that garnered praise from several Western negotiators. But Wilson, desperate to save his proposed League of Nations, traded Chinese land for Japanese support. Shandong was granted to Japan, and China left Paris as the only member of the Allies that refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles.

Nationalists back in China were incensed by the way their country was treated by the Western powers, and on May 4, 1919 gathered at Beijing’s Tiananmen Square (or rather, an early version of the square we see today) to protest. This assembly sparked what came to be called the May Fourth Movement, an explosion of nationalist fervor that led to other radical movements—most notably, the creation of the Chinese Communist Party. French’s book reminds us that World War I triggered one of the central events in twentieth-century Chinese history. And the other three authors demonstrate that even though China’s involvement in World War I is rarely thought about much today, our understanding of the war can be enriched by increasing our knowledge of how it played out in places far from the battlefields of Europe.