In a post here at the LARB China Blog last month, Austin Dean discussed the recent revival of interest in Chinese authors of the 1930s and ’40s who had fallen out of favor after the communist takeover in 1949. When Austin sent in his post for editing and I opened the file to see what he had written about, I laughed to myself — he and I were thinking along the same lines, as I had been planning a post about one of those long-lost authors.

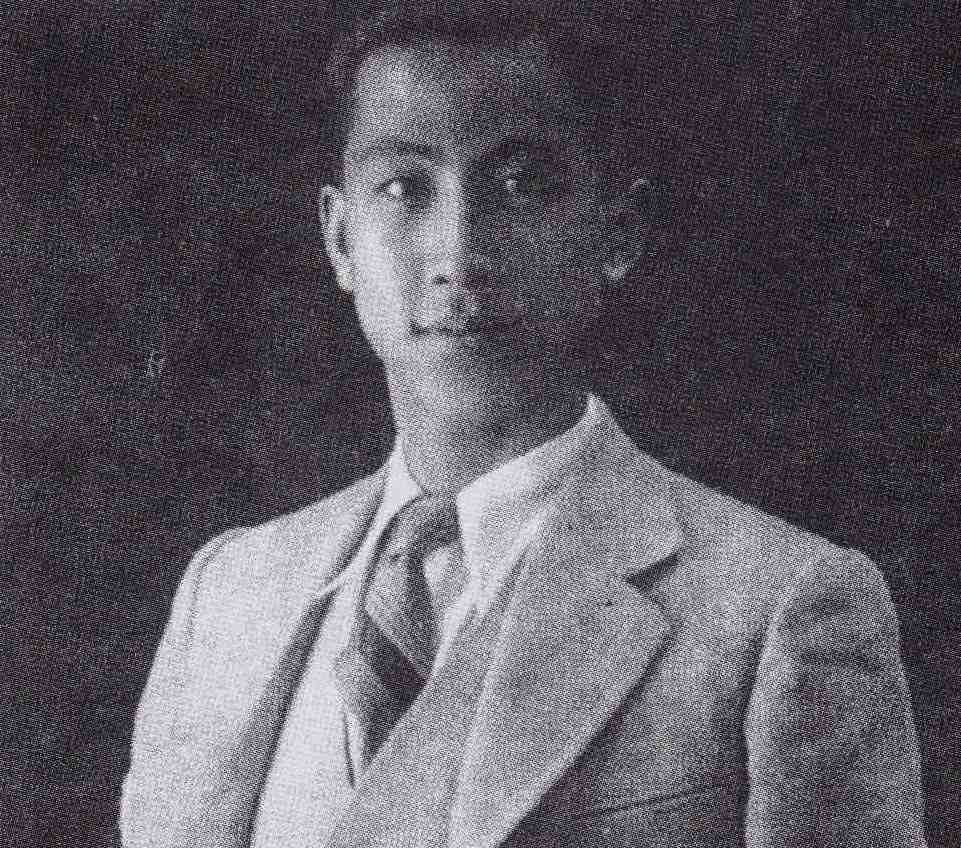

The author I had in mind was Mu Shiying, an experimental essayist, short-story writer, and novelist who blazed onto the Shanghai literary scene in the early 1930s and produced an impressive quantity of works before falling victim to an assassin in 1940. The circumstances of Mu’s death have something to do with his long disappearance from the Chinese literary canon: he had taken a job managing a newspaper produced under the Wang Jingwei regime, a collaborationist pro-Japanese government that’s still remembered as perhaps the greatest example of betrayal in twentieth-century Chinese history, and that association led to his assassination. But the other reason that Mu’s stories could not be circulated during the first few decades of communist rule is that they depict — in vibrant, thrilling detail — the pleasure-seeking wildness of Shanghai nightlife in the 1930s. In the years after the communist government came to power, the new administration shut down those nightclubs, and the major literary works of the Mao era (1949-1976) featured China’s farmers and workers, rather than tuxedo-clad cabaret patrons.

Like Shanghai’s more recent literary wunderkind, Han Han, Mu Shiying embarked on his meteoric literary career as a teenager, publishing his first story at the age of 17 and then experimenting with different genres over the following decade. The attention garnered by his early publications drew Mu into a group of avant-garde authors known as the New Sensationalists, who used their writings to convey the experience of living in the chaotic and cosmopolitan metropolis of Shanghai. Mu, a participant-observer of Shanghai’s cabaret culture, wrote extensively about the highs and lows of evenings spent in stylish nightclubs, juxtaposing images of their lavish patrons with scenes that pointed to the ways in which the city’s neon-lit fantasy world hid much harsher, and darker, realities.

Six of Mu’s short stories have now been brought to English-speaking audiences, courtesy of a new translation by scholar Andrew David Field, who previously published a monograph on Shanghai’s nightlife in the 1920s and ’30s. Field begins Mu Shiying: China’s Lost Modernist with an essay on the author’s life and the context of his work, writing that Mu “exposed the dark underbelly of a city notoriously ridden with gangsters, opium dens and prostitution, while also capturing the unbridled hedonism and boundless energy of the metropolis in its heyday.”

The stories that follow Field’s introduction invite easy comparisons to the work of F. Scott Fitzgerald — the female lead of “Five in a Nightclub” is even (perhaps not coincidentally?) an aging beauty named Daisy, a Chinese version of Fitzgerald’s Daisy Buchanan. And I could readily imagine director Baz Luhrmann turning Mu’s image-laden stories into a lavish film production, forming a trilogy of sorts with his earlier works, Moulin Rouge and The Great Gatsby. (Baz Luhrmann, if you’re reading this, I’m available as a consultant for very reasonable rates.)

But the Mu-Fitzgerald comparisons go deeper. Both served as chroniclers for their class and their generation, but neither wrote uncomplicated celebrations of nights spent foxtrotting and days spent recovering. In fact, there’s a sense of world-weariness and dutifulness to those nightclub visits, which comes through most clearly in Mu’s story “Black Peony”: evenings at cabarets were once novel and exciting, but have settled into a social obligation for the narrator, who feels “weighed down by life.” And the complex negotiations involved in romancing Shanghai’s “modern girls” vexes all of the male characters, who frequently find themselves treated as playthings by duplicitous women. Mu was particularly fascinated by Shanghai’s dance-hall hostesses (he himself married one), whom he often depicted as enthralling but calculating, attracting suitors only to take advantage of them. Mu’s protagonists, Field notes, were generally “well-to-do men of a certain generation who found themselves uneasy with the idea of women charting their own independent sexual trajectories as they made their way through the novel terrain of the modern metropolis.”

Life isn’t easy for Mu’s female characters, however. Daisy and the others might have more autonomy and sexual agency than their mothers did, but they’re still ultimately trapped by societal limitations: the expectation that they’ll get married; the expiration date on their looks; the knowledge that if they’re too explicit about acting on their sexual agency, they’ll be considered cheap. Mu’s women might have the upper hand as they play one man against another, but at some point, the tables will turn. Either they’ll marry and have to accept their husband as head of the household, or they’ll remain single and have to face the day when men’s heads no longer turn as they walk past. As Rongzi, the female lead of “The Man Who Was Treated as a Plaything,” explains, only if she marries “an extremely ugly and stupid person” will she be able to manipulate her husband and maintain a position of power in their relationship. Otherwise, her future is “husband, child, household—that would really take away my youth.” Life in the modern metropolis appears to have given Mu’s women more options, but not changed the fundamental rules of the game.

Life in the interwar nightclubs of Shanghai or New York looks attractive from a distance: elegant evening clothes, heart-pumping music, endless glasses of champagne. But as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Mu Shiying both reveal in their writings, this glamorous world also involved complicated negotiations in the relationships between men and women, and urban life ultimately offered little that was truly fulfilling. Writing that “[t]he superficial nature of human relationships, the shallow desire for people to seek out affirmation and adoration in the city’s night-time arenas, and the need for constant escapist thrills are universal features of modern urban life,” Field suggests that Mu’s stories are newly relevant in today’s Shanghai, once again an exciting cosmopolitan metropolis that all too often proves the old adage, “all that glitters is not gold.”