By Jenny Lower

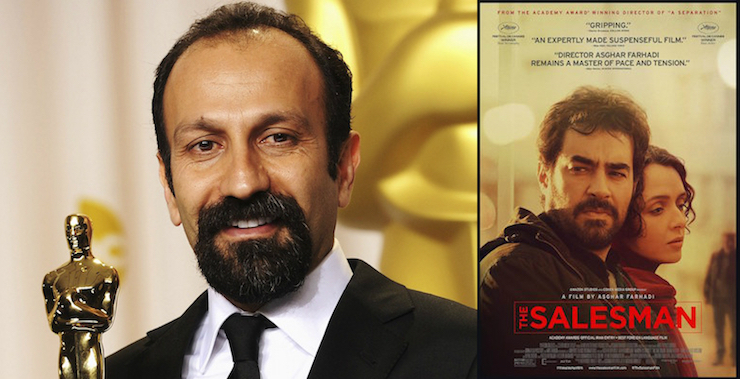

Two hours before the La La Land–Moonlight mix-up notably derailed the Oscars, Iranian filmmaker Asghar Farhadi also made history. In 2012, he became the first Iranian director to win Best Foreign Film for A Separation. On Sunday night, he did it again with The Salesman.

But Farhadi wasn’t at the ceremony to accept the award. After Trump’s travel ban was issued on January 27, barring immigration from seven Muslim-majority countries including Iran, Farhadi announced he would boycott the Oscars in protest. Though U.S. courts have since suspended the ban, Trump has promised to issue a revised order soon.

Farhadi’s acceptance speech, read by Iranian astronaut Anousheh Ansari, slammed the U.S. president without ever mentioning him by name. “Dividing the world into the ‘us’ and ‘our enemies’ categories creates fear, a deceitful justification for aggression and war,” he wrote. “Filmmakers can turn their cameras to capture shared human qualities and break stereotypes of various nationalities and religions. They create empathy between us and others, an empathy which we need today more than ever.”

American politics have swept the politically reticent Farhadi into a public role as Trump dissident and artistic martyr. The added attention likely helped win him the Oscar. But the imbroglio threatens to eclipse the film itself, which indirectly presents to American audiences a message even more barbed than Farhadi’s pointed comments.

The travel ban and Farhadi’s Oscar come at a time of deep concern for the future of American democracy. How fitting, then, that The Salesman reinterprets Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, the playwright’s devastating postwar commentary on the dissolution of the American dream. With its subversive theatrical roots and stereotype-busting portrayal of Muslims, Farhadi’s film warns us that attention must be paid to fissures like the travel ban, or the edifice of American democracy could come crumbling down.

In fact, the film opens with such an image — jagged cracks wide as a man’s finger suddenly skitter across the window of a middle-class flat in Tehran. Unregulated construction next door, it turns out, has threatened the building’s foundation. That foreshadowed instability comes to haunt the apartment’s residents, a 30-something couple costarring in a stage production of Death of a Salesman. Emad (Shahab Hosseini) and Rana (Taraneh Alidoosti) soon find themselves forced to relocate to another flat in a dingier neighborhood. There, an intruder linked to the previous tenant assaults Rana in the shower, and Emad begins a search to track down the man responsible. Though Emad is not the salesman of the film’s title, he eventually becomes a modern-day Willy Loman, defeated by circumstances beyond his control.

The crux of The Salesman rests on an unseen sequence — the assault itself, whose exact contours remain troublingly hazy, even for the characters. Farhadi relied on a similar technique in the divorce drama A Separation, in which a cascade of marital and class conflicts arise from one pivotal, invisible scene. His approach can be viewed as a coping mechanism to outmaneuver Iran’s heavily regulated film industry, where metaphor and blank spaces must stand in for more overt political or social critiques. For Americans, even the mundane details of Farhadi’s films are instructive: they offer a glimpse into the everyday lives of people whose humanity is often obscured by geopolitical posturing between the U.S. and Iran.

Farhadi shares with Miller this interest in bringing nuanced characters to life. In the 70 years since Death of a Salesman appeared, the playwright’s searing account of a middle class family’s failure to get ahead has circulated around the world—including pre-revolutionary Iran, where it was first staged in Persian in the 1960s. Willy Loman’s tragic end indicted an entire unjust economic system, but Miller was careful not to make Willy a saint.

Farhadi started his career in the theater and cites Miller among his key influences. “I see human beings as transcending politics, as transcending everything,” he said in a recent interview with Vox. Miller appealed to him because the playwright “refuses to divide people into black and white.”

Farhadi’s empathy as a director comes through most clearly in The Salesman’s prolonged third act. (Spoilers follow.) When Emad corners his wife’s attacker, he plans to exact what he believes to be justice, by revealing the man’s transgression to his family. But that plan falters once the relatives show up. The attacker ultimately turns out to be so wretched and human that instead of arousing the viewer’s anger, he stirs something approaching pity. It’s an extraordinarily generous moment of storytelling.

Even more remarkable is the behavior of Rana, whom Emad nearly forgets in the anticipation of carrying out his punishment. Despite her obvious trauma, she finds compassion. “You’re taking revenge,” she tells her husband, with a steeliness reminiscent of Linda Loman at Willy’s graveside. “Let him go.” Emad does.

This depiction of forgiveness comes at stark odds with the image of bloodthirsty Muslims painted in Trump’s January 27 travel ban. “The United States cannot, and should not, admit those who do not support the Constitution, or those who would place violent ideologies over American law,” it reads. “In addition, the United States should not admit those who engage in acts of bigotry or hatred (including “honor” killings, other forms of violence against women, or the persecution of those who practice religions different from their own).”

Not only does The Salesman contradict Muslims’ supposed “violent ideologies,” but it defies the internal logic of a good portion of America’s own films. Those movies are often rooted in extrajudicial violence, even when they are not set in America. Hollywood (and box offices) love a just man seeking vengeance for the violation of his womenfolk, from Mel Gibson’s Scottish warrior epic Braveheart to the Liam Neeson action thriller franchise Taken. The trope crops up in westerns both old and new, from John Ford’s classic The Searchers to Clint Eastwood’s Unforgiven, credited with reviving the genre in the early 1990s. Like Emad, the heroes of these films seek justice and honor, but their journeys typically end with more blood.

The Searchers, one of the most celebrated westerns ever made and starring the most iconic American actor in history, even strays into honor killing territory. In the film John Wayne’s Civil War veteran is on the trail of his niece, played by Natalie Wood. Indians abducted her years earlier after murdering her family. Wayne eventually finds her, but his plan all along is not to rescue her, but to kill her. Being held captive has turned her into “the leavin’s of a Comanche buck,” he says; death is preferable. Wayne’s ultimate failure to follow through on his plan shouldn’t appease those who believe honor killings hold no place in American culture.

Like Rana and Emad’s apartment building, American democracy is in peril, its foundation being chipped away. Cracks have fractured the windows; the ground is slipping.

“What a disaster,” Emad says at one point, looking out over the city. “If we could only raze it all and start again.”

The Trump administration certainly wants to try. Steve Bannon recently boasted of the battle for the “deconstruction of the administrative state,” as the White House works to curtail the rights of immigrants, refugees, LGBT citizens, and transgender students. And this is where The Salesman’s most potent political commentary lies less in what Farhadi’s film says about Iran than what its literary inspirations reveal about the U.S. at this moment.

Death of a Salesman documents the tragedy that results when the system gets too mean and individuals lose agency over their futures. It also serves as a kind of morality tale about the danger of failing to see those you around you or yourself clearly, at a time when basic interpretations of reality remain up for dispute. Miller recognized the power of narrative to shape and eliminate binary notions of “us” and “them.” His play, refracted through Farhadi’s film, makes both a fitting warning and a call to arms for American audiences.