By John Knight

Stephen Florida is an obsession. His body is a vehicle for conquering, the people around him are either useful or obstacles, and his mind churns, devouring everything that stands outside a single thought: “My name is Stephen Florida and I’m going to win the Division IV NCAA Championship in the 133 weight class. That’s it.”

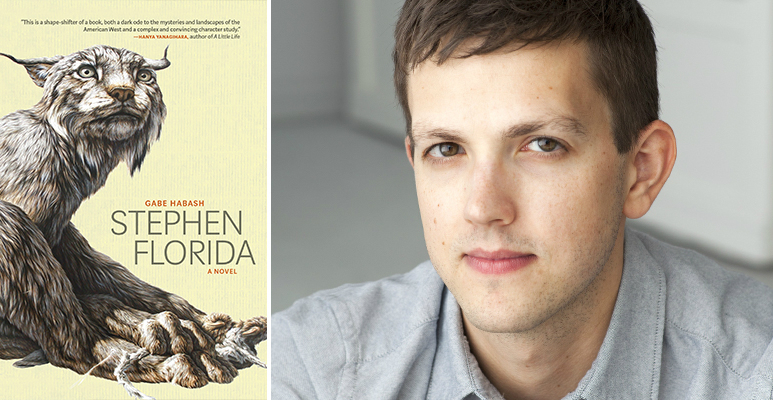

There are two difficulties in this fixation — the first is a matter of the identity of Stephen Florida, and the second concerns a wrestling championship. In Gabe Habash’s wickedly good debut novel, we see a mind relentlessly seeking to bend the world to its will, thereby weeding out the real from the unreal and finding a place for itself in between the two. If it were simply a matter of desire, Stephen Florida would have it easy — no one wants this title more. But despite everything he tells himself about who he is and what he can do, it is his body that will ultimately determine his triumph or failure.

The gap between what we wish we were and what we are is, for most people, sizable. And our ability to navigate the edges of that gap and stitch them together stands in direct relation to our sanity. If you think you are one thing but the world tells you you’re something else, you have to either amend yourself to the world, or convince the world to recognize you on your own terms. Usually it’s some combination of both, and when successful, you become who you are. But if you fail, the gap widens, the world distorts, and you find yourself going nuts.

Stephen Florida is right on that edge. He’s got five months to win the championship and he does not look any further ahead. “Why else does the world exist than to test you and see if you’re good enough to pass the test?” he asks Mary Beth, a girl who loves him but whom he won’t let himself love back because he insists on loving wrestling more. “It’s about taking control of your life, about nothing ever telling you what you’re incapable of.”

“You’re putting all your eggs in one basket,” she replies. “You have no fallback plan. You only care about one thing.”

“That’s right. Caring about the one thing makes it what it is.”

Over the course of these five months, Stephen Florida rages and trains and fights and rages some more, and sometimes attends class and does pushups and rages and runs and does more pushups. The championship is a fixture in his mind, yet it is at constant odds with his situation — he hasn’t won anything yet, and the world doesn’t care whether he does.

One spectacular feature of sports novels is the clear definition of success. Few metrics in life offer such finality as first place — you either win it, or you don’t. Most of the time, we notch our progress by benchmarks like job title, salary, marriage, and so on, but these change and can be revoked. Championships, on the other hand, while perhaps the most artificial designation there is, are also one of the most permanent.

This provides a narrow framework for the novelist, but one inherently pressurized and explosive when the pieces are torqued in the right way. It’s November now, and the championship is in March. There will be 24 matches, each about seven minutes long, which makes for 168 minutes of wrestling. “Less than three hours,” Stephen Florida tells us, “that’s what will be put down in the records, to be permanently studied by the world’s progeny, tracing the table’s lines with their fat fingers. The 168 minutes that matter.”

The difficulty, then, is the other 215,832 minutes. In each of these, Stephen Florida can’t move any physically closer to his goal, and so he’s limited to the provinces of his own mind. These stormy and twisted hinterlands, filled with creatures Florida is forever straining to contain, are the startling achievements of this book. Good sports writing is a mix of unwavering precision in describing something many people know about (the sport), and the mastery of a consuming need to win that very few share. Habash achieves both with ease, but it is his unnerving claim on the horrors of a mind enslaved by the body that makes Stephen Florida exquisite.

The book is largely one grand monologue inside Florida’s head with the occasional conversation or observational digression. Mostly it’s Florida’s mediation on what is true and worthy. At one point, he gives us this:

Am I who I said I was? Am I a wrestler? If I jump off the top of the capitol building and my spirit escapes, does my spirit upon entering another body turn again into a wrestler? Does it resume all this? Or is the link so weak that wrestling ends along with the body? Does the entire feeling end just like that? This center inside me, encoded with tilts and cradles, could go up in smoke at any moment without a body willing to do its dirty work.

These are terrible questions for Florida, and they are compounded throughout the novel by a delightful array of both real and imagined facts. Take for instance the Frogman, a shadowy hallucination that recalls Donnie Darko’s rabbit and who, Florida tells us, “is always in the room with me […] I try to keep him in the corners, try not to look, because if he’s let out and gets his way something might happen.” Or the antique gun Florida happens across at a trade show, buys, and keeps under his pillow and tucked into his belt. At one point Mary Beth tells him the story of Levi Silas, the school music teacher who supposedly killed his wife while she was in the bathtub by setting his house on fire. Florida signs up for his class on jazz and begins spying on his house.

These things don’t make any sense, yet they are packed with potential consequence, and for a reason that Habash holds carefully just out of focus, Florida can’t help but do them. He is driven by inexplicable compulsion, much like in his wrestling, and what makes his character such a enticing guide to the mayhem is that he is just wary enough of what is real and what isn’t, and that he is in constant danger of losing the ability to make the distinction. Alongside Florida’s phantoms are entire lists of what he “knows,” as if so much of life is an act of cataloging whatever comes into your orbit so as to have something real to stand on. These are indices of the world that range from a list of Florida’s romantic encounters to a note that suicidal behavior in animals has been observed most frequently in female vertebrates, and are inconsequential in every regard except that they are evidence of a world beyond Stephen Florida. And this is a proof he desperately wants. In many ways the organization of the book around the pursuit of an arbitrary, artificial, and externally validated goal — a wrestling title — serves the worthy philosophical quest to locate a secure foothold in what’s real that delivers one from an otherwise subjective prison. Through Florida’s bizarrely perceptive eyes and utterly reckless actions, we see a world of indifferent yet essential facts, as well as things that seem like facts but turn out to be something else entirely. And Florida sees all of it as data to be tested and pummeled in one direction or another.

To do this, Florida relies on the machine that is his body, and so it comes as no surprise when he breaks. After wrestling only four of his 24 matches, he tears his meniscus and is out for six weeks. Shortly after, Mary Beth is offered a job at an art gallery in Michigan that she can’t turn down. She asks him to meet her for one last diner date. She wears a dress even though it’s winter, and he stands her up. Then Florida’s only friend, Linus, suggests that maybe he could be the best wrestler in the 133 weight class. Linus is a freshman who wrestles in the 124 class but is undefeated and has begun to beat the heavier guys in practice while Florida recovers. The two were close when Florida was healthy — they bonded over a mutual drive to win — but the minute Linus becomes a potential opponent, Florida ices him out.

This leaves Stephen Florida with only his thoughts for company in the long, dark months of a North Dakota winter. He’s unable to train, unable to win, unable to do the thing that has fixed his place in the world — wrestle. So he buys a gorilla mask and tries to find and demolish Joseph Carver, the wrestler who injured his knee, but ends up losing a fight to the Carver family goat instead. He spends days alone in his room. He picks fights with frat boys while he’s on crutches. He listens to jazz and watches Linus and his other teammates wrestle. He reads The Magic Mountain. And his facts begin to mutate:

In the afternoon, I go for a long run. Down at the end of a side road, where it turns into woods, there are two hunters without orange because it’s off-season, stalking woodcocks or doves or sage grouse. In one of the fields, there are four hundred women crying facedown.

These are the best moments in the book — when Florida can’t advance his unrealized goal and has to settle for the present. Habash makes the stuff of everyday weird by straining it through Florida’s churning mind, forcing him to reckon with what is beyond his control, and to control what isn’t. Eventually his knee heals, but the assistant coach — a vindictive man named Fink — refuses to let him back on the mat. Florida wages war on this man with the desperation of a caged animal. This is another staid feature of good sports writing: nothing comes easy. The constellations of drama consist of the points just beyond a champion’s design and his infinite if illogical drive to surmount them all.

“More and more things keep happening to me,” Florida says at one point. “Insignificant things and significant things and boring things and sacred things and terrible things and nice things and strange things. They disguise themselves as new events but I really know what they are, they’re ancient events that have happened before and they’ve just run to the back of the line to wait their turn again.”

The triumph of Stephen Florida is a portrait of a young man trying to see all these pieces of the world, and in some meaningful way to make them his own. This occurs both in the moments of action — when Stephen Florida is wrestling, doing what he was meant to do — but also in the solitary stretches between one act and the next that are so often dismissed as inconsequential or dull. These are minutes when we forget ourselves while pouring a glass of milk, or running, or listening, only to be suddenly jerked back into the world. Habash finds the shards of a self in these moments and the spaces they open. They are not pretty, which is not only revealing, but accurate; they reveal the mysterious and frustrating phenomena of having a body that can only do one thing at a time while the mind rages in its cage.

“There is no Stephen Florida,” Stephen Florida tells us at one point. “I am only a giant collection of gas and light and will.” This is about right. The single person we are often pales in comparison to all we must feel and face, all that stays within, unrecognized, untested, unsung. And yet what other option do we have? Stephen Florida is an obsession, but not just with wrestling — he is the taut, erratic, boundless contradiction of what it means to be alive.