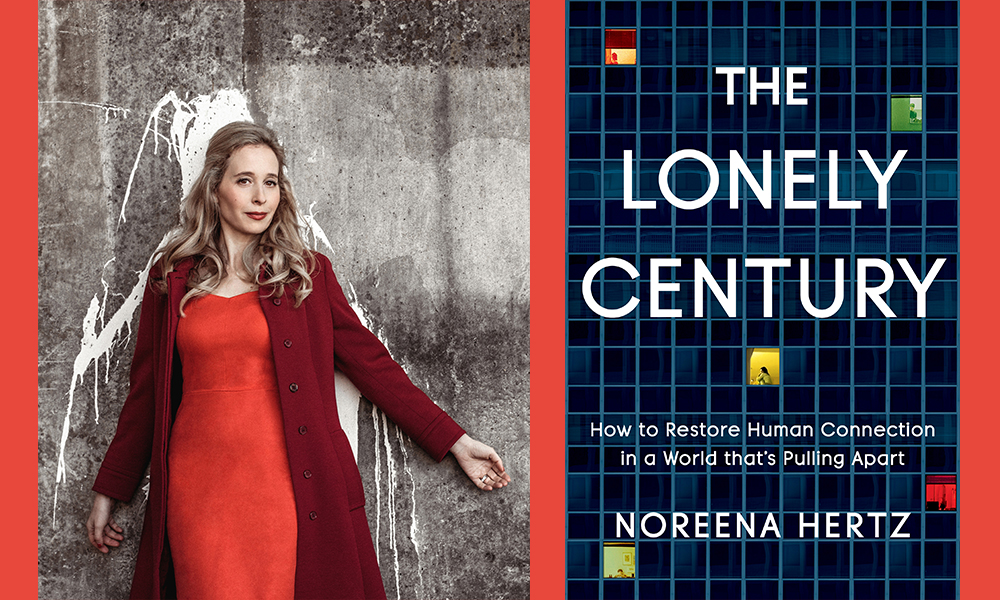

What has made us come to see ourselves as “competitors rather than collaborators… consumers rather than citizens… hustlers rather than helpers”? What makes social media “the 21st century’s tobacco industry”? When I want to ask such questions, I pose them to Noreena Hertz. This present conversation focuses on Hertz’s book The Lonely Century: How to Restore Human Connection in a World That’s Pulling Apart. Hertz has been named by The Observer ”one of the world’s leading thinkers,” and by Vogue ”one of the world’s most inspiring women.” Her previous bestsellers (The Silent Takeover, The Debt Threat, and Eyes Wide Open) have been published in more than 20 countries, and her opinion pieces have appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Wall Street Journal, The Guardian, and the Financial Times. She has hosted her own show on SiriusXM, and has spoken at TED, the World Economic Forum in Davos, and Google Zeitgeist. Hertz is based at University College London, where she holds an honorary professorship.

¤

ANDY FITCH: Could you first sketch what it might look like to think about loneliness holistically: factoring in for example 21st-century forces of globalization, urbanization, increased mobility and technological disruption, neoliberal policy trends making structures of social support more brittle, long-standing institutional discrimination, escalating inequality and power asymmetries — as well as individual choices, behavior, and of course feelings?

NOREENA HERTZ: We typically think about loneliness as feeling disconnected from friends and family, and craving their support and care. Loneliness is of course this too. But I define loneliness also in terms of feeling unsupported and disconnected from our political leaders, our employers, our fellow citizens, feeling invisible and unheard by those holding power as well as by those ostensibly closest to us. For me, this makes loneliness political as much as personal. And it has clear structural (economic and technological) drivers, as well as being a feeling emanating from and fueled by the choices that we as individuals make about how we behave with and to each other.

This broader definition of loneliness comes out of an intellectual tradition: whether Hannah Arendt’s work on loneliness as a driver for totalitarianism’s rise in Nazi Germany, Émile Durkheim’s view of anomie as a state of isolation, or Karl Marx’s notion of alienation. Like me, these thinkers all have seen loneliness as something of an existential state, as well as an individual feeling.

With those three thinkers in mind, your definitional treatment of loneliness also stresses a palpable sense of loss, including loss of community, economic security, social standing. Your account of Donald Trump rhetorically tapping these communal senses of loss (even while his administration’s policies often exacerbated those losses) made me wonder how you might hope for political leaders in the US, the UK, the EU to harness the more redeemable aspects of present-day populist identifications. How might leaders speak most constructively to which of today’s most lonely-making (yet potentially galvanizing) grievances?

Well first of all, we do need to acknowledge there is a palpable and desperate craving for community and care out there. Many people feel uncared for and invisible today, especially perhaps those for whom such feelings are relatively new — such as white working-class men, who traditionally would have felt the brotherhood of the workplace and the fraternity of the trade union, and would have had a sense of standing within their community. In social and economic terms, this group has in some ways lost the most over the past 40 years, leaving it especially lonely, especially craving community, and wanting to be seen and heard. Right-wing populists including Donald Trump understand and speak to that craving, with their weaponization of community (albeit in a particularly excluding form).

So how can more inclusive leaders speak to this same craving? Essentially there’s a need to reconnect capitalism with community and compassion. And there is precedent for this. In the Great Depression’s wake in the 1930s, Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal very much recognized the need both to provide immediate aid and also to boost the status and enhance the rights of those hardest hit by the economic downturn. In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service emerged in the wake of World War Two, addressing people’s immediate needs and also providing a symbol of society’s commitment to equity and compassion.

COVID-19 of course has brought us today to a very particular stage of amplified loneliness and sense of crisis. We should use this moment to really rethink priorities. The new US administration making unity an explicit part of its agenda certainly helps, as does their commitment to ramp up government spending. It’s crucial for all of our citizens to feel assured that the government is there to support them — especially now, when we know that this pandemic has not affected all of society equally. We weren’t “all in it together” after all. In fact, this pandemic only has exacerbated entrenched inequalities. And the needs and concerns of the aggrieved constituency you mentioned must be heard and addressed.

Similarly, a significant body of research shows that, while any of us might get lonely, certain groups face more loneliness than others — with the unemployed especially lonely. With our rising unemployment figures right now, it will be absolutely critical that workers can find decent jobs, especially since we’ve also witnessed rising levels of automation, which inevitably will hit the lower skilled first and hardest. Ensuring people have dignified jobs is thus an important part of what government at the federal and state level needs to do moving forward.

We need a new body of legislation to protect 21st-century worker rights, to ensure all workers earn a living wage, and receive adequate safety and health provisions, and paid sick and family leave. Such measures shape people’s sense that the state does in fact care for them.

We have lots of creative possibilities for new job creation. We can and should create a whole host of jobs in the green economy. We also should create many more jobs specifically designated to help alleviate others’ loneliness. In the UK, many of our medical practices now have social prescribers, staff charged with helping patients find art classes, and sports activities and groups, and with helping them to build up their social lives. Society as a whole benefits from hiring more workers to provide care and support — for the elderly, for example.

At the same time, we urgently need to replenish what we might think of as the infrastructure of community. Since 2008 (and not just in the US, but all over the globe) we’ve witnessed the steady defunding of public spaces where people come together: libraries, youth clubs, community centers, centers for the elderly, physical spaces where we can relax and interact. We will never find common ground if there are no physical spaces we share.

Sure, and my previous question on Trumpers or Brexiteers also may distract from the fact that while growing older definitely makes many of us lonely, younger populations might suffer most from loneliness today — with one in five US millennials saying they have no friends, and with the stats getting even more alarming for subsequent age cohorts. Has technology, in these terms, also divided us by age much more than ever?

Well we do typically think of loneliness as something that afflicts the elderly. But actually the young have become the loneliest. A shocking number report, as you mentioned, not having a single friend. Three in five under-24s report feeling lonely often or sometimes. Teenagers and children provide even more worrisome numbers. We also know that this epidemic has exacerbated those trends. Months of lockdowns and stay-at-home orders and self-isolation have only added to young people’s loneliness.

Even before the pandemic, of course, social media and screen technologies had become major drivers for this particular form of loneliness. I began my research quite agnostic on the role that social media played. I mean, I knew I’d need to investigate it. Ever since smartphones became ubiquitous, we’ve seen this steady rise in loneliness among the young. So there clearly was a correlation. But only about 18 months ago did definitive empirical evidence emerge that social media actually make people lonely. A major gold-standard of a study conducted at Stanford University (in which three thousand people were divided into two groups, with half allowed typical computer and smart-phone and social-media usage, and the other half charged not to use Facebook for two months) gave unequivocal results. Those who stopped using Facebook spent considerably more time interacting face-to-face with friends and family. They felt significantly happier, and significantly less lonely. Subsequent studies have essentially replicated those findings for other social-media platforms.

That all provides empirical weight to the kinds of anecdotal evidence so many of us have seen. For my own interviews with teenagers, their stories of social media’s pernicious influence came up time and time again. Peter, a 14-year-old, poignantly described posting on Instagram and then waiting, waiting, waiting — hoping somebody would like his post, feeling so invisible when nobody did, asking himself what he’d done wrong. Or Claudia described schoolmates telling her they wouldn’t be going out that night, but then scrolling down her social-media page and seeing them out together having fun, and hiding in her bedroom for a week. Those types of exclusion always have happened. But kids never before had the possibility to witness their personal exclusion 24/7 like this. And adults, by contrast, often are unaware that this exclusion is taking place, because so much of children’s social lives now takes place on social media, invisible to the outside eye.

Talking to these teenagers really strengthened my sense of the extent to which social media negatively affect so many children’s mental health, and impact how lonely they feel. I’d go so far as to describe social media really as in many ways the 21st century’s tobacco industry — peddling an incredibly addictive drug with pronounced harmful effects, deserving to be regulated as such. I call, in fact, for a ban on addictive social media when it comes to children under age 16, thereby putting the onus on social-media companies to design new products less addictive and hopefully less cruel. Today 65 percent of UK students, for example, have experienced cyber bullying first-hand.

And it’s not just children addicted to their phones. Many of us are guilty of this, me included. We’ve all had the experience of being so distracted by our phones that we’ve almost been unable to hear the people around us. This despite the fact that, as with fast-food, the more we gorge on Facebook or Twitter interactions, the less sated we typically feel. Of course, during the pandemic, our limited choice has made some of these inferior virtual interactions our only viable option to connect.

Returning then to a diagnostic account of 21st-century loneliness, specific technological products, such as smart phones and social-media networks, have no doubt reshaped huge swathes of our lived experience. But again in terms of your holistic approach, could you begin to situate these products within broader ecosystemic structures? Could you trace from these present trends, for example, the contours of an increasingly contactless age coming into being?

Right, even before the pandemic, we could see a rise in contactless interactions, in people choosing to shop, exercise, eat, without ever having to interact with someone else. We already had a rise in the numbers of people ordering food via GrubHub or DoorDash, or buying Peloton bikes and doing their spin classes that way. Amazon already had begun launching US stores with no staff, with thousands of mounted cameras monitoring what you take, so that you never need to speak to a checkout person (a person no longer even there). I started writing this book with these trends in mind, and then the pandemic accelerated all of them — with millions of people working from home, shopping even for groceries online, and flocking to do yoga with Adriene on YouTube.

Now, as we begin to contemplate post-pandemic society, we face a real danger that contactless interactions will become further institutionalized, thereby depriving us of two crucial aspects of everyday living. First, we could lose even more of what I call micro-exchanges, those short interactions at the yoga studio when we kind of smile at the person on the mat beside ours, or chat for a few minutes after class, or talk for a minute with the baristas when we pick up our coffee. Those small interactions actually play a huge part in making us feel connected to each other and less alone. Research shows that even a 30-second exchange has a marked impact, both on individual and on societal well-being.

These face-to-face encounters in the yoga studio, in the grocery aisle, also provide one of our main ways to keep practicing how to interact with each other, how to cultivate community and even reinvigorate democracy. Just that instant reflection of Oh, can I put my yoga mat here, or has someone else already claimed this space, just negotiating the grocery aisle with your trolley — those moments in our day-to-day existence force us to think about others’ needs, to take their perspectives into consideration. We should consider these moments some of the absolute essential building blocks for an inclusive and thriving democracy. By contrast, if we keep walking down the path towards contactless existence, we’ll end up feeling both more lonely and less skilled at stitching together our democracy.

Here again on an ecosystemic level, could you outline a couple trends making today’s cities “increasingly… epicenters for isolation”? And given projections for accelerating urban migration worldwide, which most acute loneliness factors of atomized urban living will both municipal governments and individual residents proactively need to address?

We tend to behave certain ways in cities. It turns out that the richer the city, the faster its people walk. The denser the city, the less civility its residents show to each other. In dense, fast-paced cities, we rush past each other. We don’t look each other in the eye. With so many people around, the default response is to just not say anything to anyone as you pass, and not acknowledge each other’s physical presence in the way you might in the local grocer’s aisle. Our way of coping in dense urban spaces often means withdrawing into one’s own digital-privacy bubble, with headphones on, not even glancing at passersby.

Much of this isn’t new, of course. My book cites Thomas De Quincey writing about 19th-century London feeling rushed and impersonal and lonely in all of these ways. Yet even before the pandemic, 52 percent of New Yorkers felt lonely. 56 percent of Londoners felt lonely. Big cities are lonely places. So what can we do about it?

In the most personal sense, we can make a conscious point of slowing down. We can pause for a beat, or kind of nod at somebody passing by, or stop for a 10-second chat with our neighbor. The pandemic has made many of us appreciate our own local neighborhoods, and be more open to nurturing relationships within them.

We also could go even further. A couple of years back one woman in Wales, Allison Owen-Jones, basically asked herself: “Well, how can I identify someone passing by who feels lonely, looking for somebody to speak to?” So she set up what she called “Happy to chat” benches. On certain public benches she put a little sign that said: “Sit here if you don’t mind someone stopping to say hello.” By sitting on this bench, you signaled your interest in having somebody share the bench and chat with you. That lovely initiative could even just about work in our socially distanced age. Perched on opposite sides of the bench, you’d probably be two meters apart, and still able to interact.

Then on a broader level of urban policy, we need to face the fact that many of our cities weren’t designed with community and connection at their heart. Two recent examples of reimagining urban spaces stand out. Certain Barcelona neighborhoods have been designated for pedestrian activity, with vehicle through-traffic banned. The city calls these superblocks. A significant body of research shows that in pedestrianized areas like this, residents feel more connected to others living there. They have perhaps three times as many neighborhood friends and acquaintances. That’s one inspiring model for urban planners when it comes to reclaiming streets for people, for families, for communities.

A second example comes from a lovely initiative in Chicago under former Mayor Rahm Emanuel. Certain public-housing developments commissioned during his time in office have Chicago Public Library branches on the ground floor. Chicago built these housing developments into community hubs from the start. Their libraries attract other residents from all around the neighborhood — people from various socioeconomic groups. Again this shows how thoughtfully designed public spaces can encourage people to come together and feel part of a broader constituency.

Shifting now to occupational spaces, could you first give a couple examples of how reorganized work environments in recent decades have intensified worker loneliness — in ways often proving counterproductive even for their profit-driven employers?

One considerable irony comes from the fact that evolving trends in workplace design, ostensibly initiated to make employees more collaborative and also more productive, have ended up making many workers feel less connected to each other, and have made them less productive. Open-plan offices, counterintuitively, have made many employees withdraw from each other. Research tracking behavior when workers move from a traditional setup to an open-plan office shows that employees communicate far less face-to-face than they had before. They use email and messaging much more frequently.

In many ways, this actually makes sense. In panopticon spaces where everyone’s always watching you, where you have no privacy, you might feel much less inclined to present your authentic self, and much more caught up in a constant performance. Or as in dense urban spaces, you might instinctively distance yourself from others, and put on your noise-canceling headphones, and keep your head down. Of course with hot desking (one of the latest fads, an open-plan office with no permanent desks for individual workers), you can’t even hang a photo of your child or bring in a plant. You might constantly move from seat to seat. Professional employees can end up feeling like interim nomads, not even knowing the person sitting beside them, not even having their own absence noticed by coworkers. In the book I talk about Carla, who had to take a number of weeks off after having an operation, but whose colleagues didn’t even realize she had gone, because each day she’d sat somewhere else.

Then in less physical terms, increasingly digitized and endlessly monitored environments also can alienate workers (and not only in an immediate, experiential sense) by shifting workplace leverage ever further towards a handful of engineers and algorithmic operations offering little transparency and accountability. Again, what do those vast asymmetries of information, and that particular form of powerlessness, have to do with a pervasive sense of loneliness today?

I do consider powerlessness and loneliness inextricably linked. It can feel incredibly lonely when you have no choice about how your boss treats you, or how your employer’s organizational processes seek to manage your behavior. During an era of steadily eroded collective voice in the workplace, with trade unions’ presence increasingly diminished, growing numbers of employees feel they have no choice but to accept being subjugated to surveillance technology, even on their laptops as they work from home. They also have no recourse to resist employers handing over decisions to algorithms, even when it comes to hiring or firing. It’s been really interesting over the last few months to see a kind of increasing momentum (albeit, starting from an almost-nonexistent base) towards white-collar workers at tech firms like Alphabet joining trade unions — in part as a way to counter this sense of loneliness and powerlessness as an employee left on your own in the depersonalized workplace.

Scenes of Amazon ruthlessly scrutinizing its warehouse workers’ every move offer another dystopic glimpse of today’s employment ecosystems. Yet how might the supposedly contrasting freedom of gig workers speak to a whole additional range of concerns — and help to catalyze recognitions that: “We sleepwalk into the next wave of automation and technological disruption at our peril”?

While some gig-economy workers do choose this arrangement and feel a clear sense of agency, significant numbers do not. They feel painfully subjected to precarious employee status, to unpredictable hours, to tolerating various forms of unfair treatment just in order to keep earning a living. Of course that lack of agency again can feel quite isolating. So for many reasons I consider it essential that our societies establish gig-economy workers’ right to be treated decently on the job, as well as to receive adequate pay.

We need to do this now, because workplace automation will only put more of us in these more precarious positions. Blue-collar manufacturing workers might have been first to see their jobs taken over by robots. But many service-sector workers will soon see the same. In Los Angeles, for example, I visited Flippy, the burger-flipping robot who will never mistake the spatulas for raw meat or cooked meat, who always will show up on time at the burger shack, and will never request a vacation. No human will outperform Flippy in those terms.

And once again, these workplace transformations won’t just impact blue-collar workers. Journalists and actuaries and lawyers and radiographers and a whole host of white-collar professionals will see increasing numbers of jobs supplanted by robots. China already has an AI news anchor. Germany has an AI robot priest, Bless U-2, who has supplanted the local clergyman. Understandably, given the need to focus on this pandemic right now, we’ve really taken our eye off the ball when it comes to the implications of lost human occupations — which now will accelerate massively in the coming years. The pandemic of course has made every company more conscious about overhead, seeking to slash labor costs, and looking to automate faster than ever.

You also describe a broader Loneliness Economy already supporting and at times exploiting those who feel alone. Which general concerns stand out most to you as drug companies race to patent loneliness pills, as millions tune into muckbang, as consumers increasingly rent friends and cuddlers, or as developers build out their co-living portfolios?

I’m excited at the potential the market can play when it comes to helping alleviate loneliness. And you’re right my book looks at this in depth. There are some rich and fascinating stories, including my own experience renting a friend in Manhattan. But my main concerns center around access: who will have the chance to access loneliness-alleviating goods and services? Who will be able to afford such offerings? Will only the rich not be lonely? And to what extent will the “community” sold to us be real? Authentic community cannot take the form of WeWashing.

More generally, this Loneliness Economy raises serious implications for social cohesion. For if we do come to subcontract friendship and care to the market, the danger is that, in the process, we’ll dispense many of our own obligations to help each other, and become less skilled in doing so.

Yeah for a few longer-term trends, classic forms of loneliness might make us more angry, distrusting, overtly aggressive — but the futuristic scenarios you sketch also point to possibilities for all-consuming narcissistic self-absorption, for further atrophy of our capacities for care, constructive pluralism, basic democratic functioning. So how might we need to recalibrate the value placed on expanded prospects for self-determination, alongside an ongoing need for decency, compromise, and at times personal sacrifice for the greater good?

We actually have seen this trend, I would argue, since the 1980s, when a particular form of neoliberal capitalism came into effect. This “greed is good” form of capitalism, championed by Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, offered a mindset which valorized selfishness, and disregarded the importance of community. Within this mindset, we came to see ourselves as competitors rather than collaborators, as consumers rather than citizens, as hustlers rather than helpers — which in many ways was a rational response to the thought that: If I don’t help myself, who will?

That broad neoliberal impact even registered in pop-song lyrics, which from the 1980s onwards reduced their emphasis on collectivist terms such as “we,” “our,” “share” — in favor of terms such as “I,” “me,” “my.” Neoliberalism has encouraged us to become a self-centered, self-interested society, and almost inevitably therefore a more lonely one.

Moving forward, we’ll need to recognize better these foundational tradeoffs between individualism and collectivism, between self-interest and societal good, between convenience and caring — at times even between liberty and fraternity. Neoliberalism might have promised us certain new freedoms coming at no cost. But we do need to recognize the huge costs of those arrangements.

Finally then, with refocused agency still in mind, could you flesh out the foundational empowering point that often we best fend off our own loneliness by addressing the needs of others, by giving more than taking, by contributing to (rather than immediately benefiting from) the society we want to see?

This is an important point to raise, especially given that each of us is likely experiencing loneliness right now, either directly or by witnessing friends, family members, and coworkers struggle with it.

Indeed, if there’s one thing each of us could do right now, it would be to think about who in our own network might be lonely, and reach out to them. By doing so we can make a real difference to them, while also helping ourselves. When we reach out to others, we not only help alleviate their loneliness. We benefit too, both mentally and physically. People who give more than take tend not only to live happier lives — but longer ones.